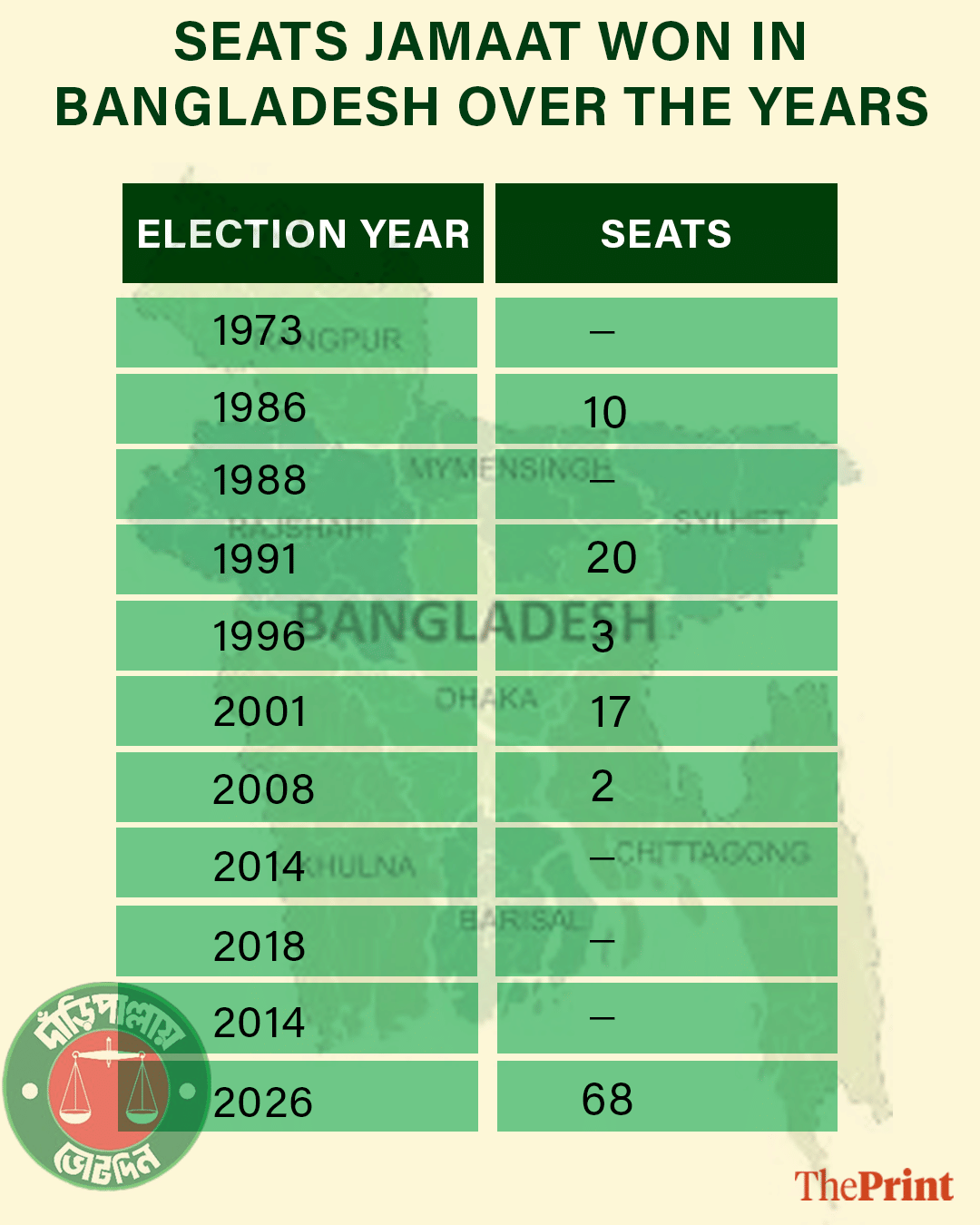

Dhaka: For the Jamaat-e-Islami, the just-concluded election in Bangladesh was significant in more ways than one. Not only did it achieve its highest vote tally and share ever, it also secured three-quarters of its parliamentary seats from areas along the politically sensitive border with India.

Analysts ThePrint spoke to pointed to Jamaat’s rising influence in economically backward rural areas, many of which lie along the border with India, and have experienced communal tensions and citizenship controversies in recent years.

Overall, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) swept the election with a majority of 208 seats, while the once-banned Jamaat, which took part in electoral politics after 13 years, became the second-largest party with 68 of the 299 seats.

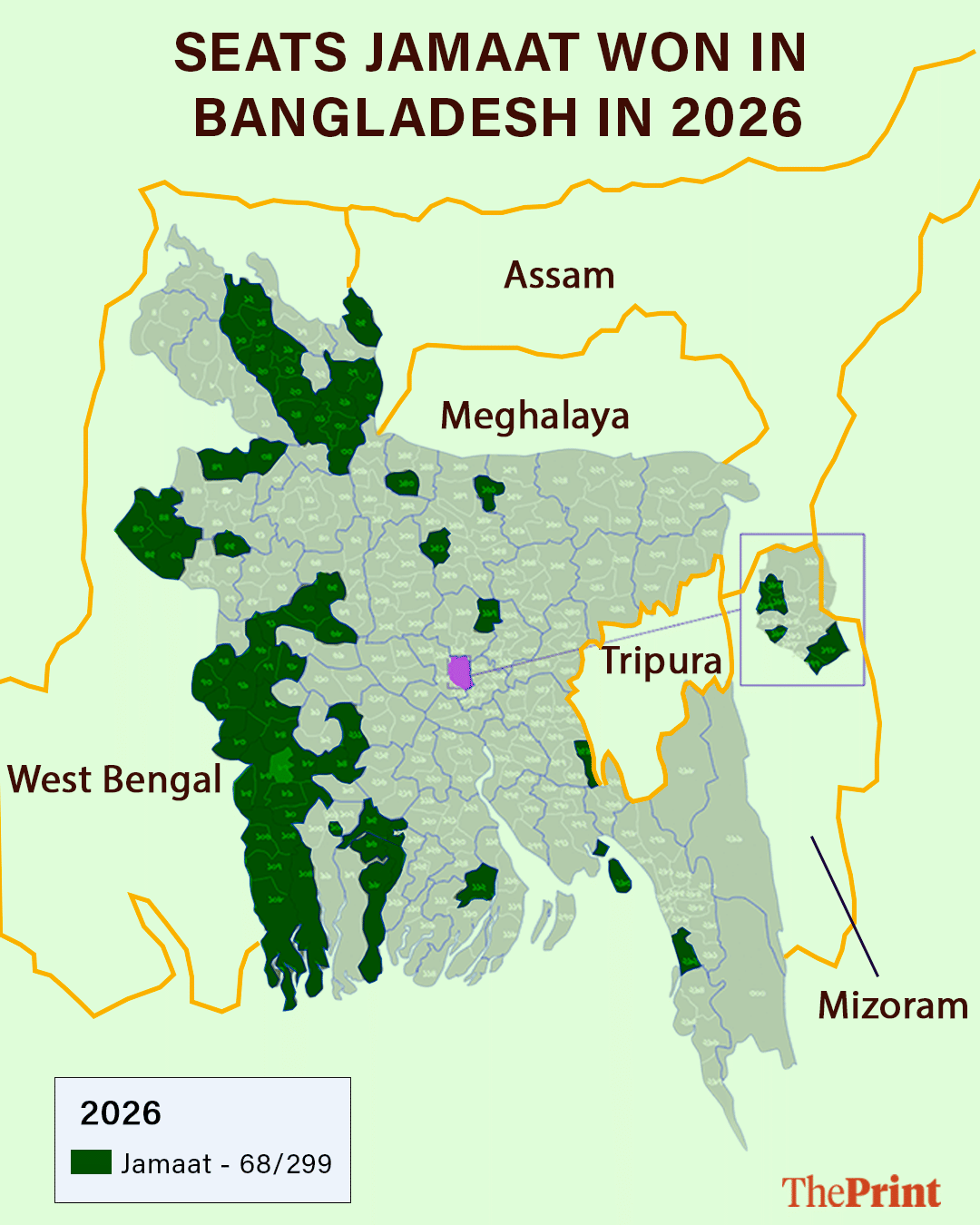

Jamaat won 58 of the 208 seats in six divisions bordering India. Of these, 36 were in areas bordering West Bengal and 16 near Assam, while the rest were near the northeast. Though most of Jamaat’s victories were in India-bordering divisions, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) still dominated these areas with 150 seats.

“Traditionally, its (Jamaat’s) vote bank has been concentrated in rural and border districts, where anti-India sentiment runs deeper and historical memories of violence continue to shape political attitudes. That context helps explain its consolidation along the frontier,” Asif bin Ali, a Bangladeshi geopolitical analyst, told ThePrint.

Bangladesh shares a 4,096-km border with India, the sixth-longest land boundary in the world, which is also called the Radcliffe Line. The frontier touches six Bangladeshi divisions: Rangpur, Rajshahi, Khulna, Mymensingh, Sylhet and Chittagong.

Of these, the stretches adjacent to India’s West Bengal and Assam are viewed as the most politically sensitive.

The areas bordering West Bengal are Rajshahi, Rangpur, Khulna, and minor parts of the Dhaka and Mymensingh divisions. The regions bordering Assam are the Rangpur and Sylhet divisions.

Jamaat’s performance in the border areas is significant. It won its highest number of seats in Khulna division—25 of 36 seats—followed by Rangpur with 16 of 33 seats, and Rajshahi at 11 of 39. Its vote share was 48.26 percent in Khulna, 39.78 percent in Rangpur and 39.71 percent in Rajshahi, according to Bangladesh Election Commission data.

In Khulna, it won three out of four seats in Kushtia, all two seats in Meherpur and Chuadanga, one out of two in Jhenaidah, five of six seats in Jessore, and all four in Satkhira.

It also won two seats in the Barishal division, eight in Dhaka division, three each in Mymensingh and Chittagong, but none in Sylhet. Barishal and Dhaka are not border divisions.

Also Read: With nearly one-third of vote share, Jamaat pulled off in Bangladesh what it couldn’t in Pakistan

Assam-West Bengal border

The northern belt, touching Assam and northern West Bengal, has become Jamaat’s primary stronghold. Its most impressive win in the area was in the Rangpur division, where it got 16 seats.

Rangpur division borders the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Meghalaya, and lies close to Bhutan and Nepal through India’s narrow Siliguri Corridor. China is also geographically near, separated by the Indian state of Sikkim.

Rangpur has long been considered a stronghold of the Jatiyo Party, founded by former military ruler H.M. Ershad. The party dominated the northern division for decades, often winning seats by large margins. But this time around, it won just one seat, that too in the Barishal division.

In the last three general elections, the Awami League (AL) won three of six key seats—Rangpur, Lalmonirhat and Nilphamari—in the Rangpur division.

Jamaat won big in other northern areas bordering Assam and Bengal. It got all four seats in Nilphamari, two of three seats in Kurigram, and five out of six in Rangpur city.

In other northern border areas, the BNP retained Lalmonirhat, winning all three seats, and parts of Dinajpur where it won five out of six seats, while one went to an independent.

Further south along the West Bengal frontier, Jamaat performed competitively but not dominantly. It won 30 seats in these areas compared with the BNP’s 45.

The BNP led overall in border areas, but Jamaat’s footprint is substantial and geographically clustered, especially in the north and southwest.

In the Rajshahi division, which borders West Bengal’s Malda and Murshidabad districts, Jamaat won seven seats—four in Chapai Nawabganj and three in Rajshahi constituencies. It won one each in Joypur and Naogaon. The BNP, however, captured 17 seats there.

“Jamaat-e-Islami’s surge in Bangladesh bordering towns is driven by voter anger against the established party, a desire for an honest alternative to the hijacked alternative, and strong grassroots operational discipline is also another issue,” human rights activist Rezaur Rahman Lenin told The Print. “Their social welfare initiative and conservative religious appeal resonate in this area better.”

He also said that voter extortion and inefficient local leadership of mainstream parties—including the Awami League, and later the BNP in rural areas and urban peripheries—pushed voters towards Jamaat.

Lenin said its organisational strength and welfare initiatives at the grassroots level, including schools, health care services, and community infrastructure, also added to its appeal.

He added that as a conservative Islamic party gradually taking a moderate stance, though rooted in Muslim identity, it attracted voters in regions that felt disconnected from Dhaka’s more secular-leaning political discourse. At the same time, voters were also looking for an alternative in the face of a leadership vacuum to a certain extent, he further said.

“What is more striking, and perhaps more concerning, is its performance in Dhaka. It signals that Jamaat’s appeal is no longer confined to peripheral or border regions; it is making inroads into the urban political mainstream,” Aif bin Ali added.

The picture changed sharply in areas bordering India’s Northeast, where Jamaat’s appeal was limited.

In Sylhet division, for instance, which borders Assam and Meghalaya, Jamaat won no seats independently while the BNP swept all 19 constituencies. Its ally, Khelafat, won one seat in the region in the Sylhet-5 district.

In the Mymensingh division, which borders Meghalaya, Tripura, Assam and Mizoram, Jamaat managed only three seats compared to the BNP’s 15. In the Chittagong division, bordering Tripura and Mizoram, Jamaat won three seats while the BNP captured 45.

Why Jamaat’s border wins matter for India

For India, particularly the states of West Bengal and Assam, these results are not immediately alarming.

The BNP remains the dominant political force across the border belt. With 124 of 160 border-division seats, the nationalist party overwhelmingly controls the frontier narrative. Yet Jamaat’s concentration in Rangpur, directly across from Assam, introduces a new variable.

Northern Bangladesh has historically been economically marginalised and migration-sensitive. Any ideological consolidation there intersects with long-standing Indian anxieties over cross-border migration, identity politics in Assam and communal polarisation in West Bengal.

However, the data does not indicate a broader Jamaat takeover of the border. Rather, it shows that Jamaat’s growth is selective and regional. Its inability to win in Sylhet, despite its proximity to Assam and strong religious networks, shows the limits of its appeal.

From Dhaka’s perspective, the frontier remains largely under the BNP’s political control. From New Delhi’s perspective, the absence of a sweeping Jamaat surge may temper immediate geopolitical concerns.

How allies performed along border areas

While Jamaat remains the most significant Islamist force numerically, smaller allies have also made targeted gains in this frontier zone.

The Nationalist Citizens Party (NCP) won three seats in India-bordering divisions: Rangpur-4 and Kurigram-2 in Rangpur Division, and Comilla-4 in Chittagong Division.

The Khelafat Majlis secured one border seat in Sylhet Division, a region that shares a boundary with Assam and Meghalaya, and has historically maintained religious networks with India’s northeast. Its second national victory, in Madaripur-1, is outside the border zone.

Similarly, the Bangladesh Khelafat Majlis captured Mymensingh-2, giving it a single seat in the India-bordering divisions. Mymensingh touches the Assam frontier and has periodically figured in cross-border political discussions.

In contrast, Islami Andolon Bangladesh, despite winning Barguna-1 nationally, has no representation in any of the six India-bordering divisions.

Taken together, these smaller parties account for five seats along Bangladesh’s India frontier: three for the NCP, one for Khelafat Majlis and one for Bangladesh Khelafat Majlis.

Though modest in number, their presence is geographically notable—stretching from the northern districts of Rangpur to the eastern plains of Sylhet and the southeastern expanse of Comilla.

“One of the main explanations for a Jamaat victory begins with the fact that in the last 15 to17 years it was one of the biggest targets, biggest victims of Awami League repression,” Waresul Karim, a professor at North South University in Dhaka and one of the key architects of Jamaat’s manifesto, told ThePrint.

Many Jamaat workers and activists were displaced, and in places like the border areas of Satkhira, homes were allegedly bulldozed. In a freer political atmosphere, people often sympathise with those they perceive as oppressed. Since BNP and Jamaat were together for the last 35 years, repression of one frequently affected the other, he added.

The alignment of student groups, particularly through the NCP, gave Jamaat what he described as “a semblance of modernity” and helped counter portrayals of the party as backward-looking.

“Their consistent support for reform proposals from the National Consensus Commission—including separation of powers between president and prime minister and institutional reforms—reinforced this perception, especially when the BNP appeared reluctant on some reforms,” Karim added.

A third factor, according to Karim, is that “Jamaat’s support base has never been accurately estimated”. He said its historical vote share—12.6 percent in 1991 or 8.4 percent in 1996—may not reflect its rue strength because tactical voting blurred distinctions between BNP and Jamaat supporters.

In multi-party contests, voters may shift strategically toward the most electable opposition candidate. Instead, he suggests that Jamaat’s “real strength” may have been higher than official figures indicated.

He said that “Jamaat is one of the most misunderstood political parties in recent history”. While acknowledging that “their 1971 role is undeniable”, he believes that this legacy has overshadowed what supporters describe as their “non-corrupt image” and relatable candidates.

They lack “heavyweight, unapproachable millionaires” and instead field candidates from modest professional backgrounds, he added.

Karim stated that Jamaat would not pursue confrontational or radical shifts, saying they were “not going to form a paramilitary” or destabilise border regions.

He rejected the characterisation that they aim to push Bangladesh toward extremism, calling that narrative “bogus” and part of earlier fear-based political messaging.

He expressed hope that improved understanding could prevent misperceptions, noting that Jamaat is not inherently anti-India and would likely maintain pragmatic relations.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Ban to breakthrough—Jamaat ends political exile, redraws Bangladesh’s opposition landscape