The government of The Gambia recently announced that the country had eliminated trachoma, a highly contagious eye disease, after years of hard work by health workers, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and communities.

In The Gambia, the disease accounted for 17% of the reported blindness in a national survey in 1986. The prevalence of trachoma has dropped from 0.1% to 0.02% in the last 10 years. Current estimates show a prevalence of less than 0.2% in adults aged over 15 years. This is about one case per 1,000 people.

Trachoma has been described as the most infectious cause of blindness in the world, responsible for 1.4% of blindness. It is one of the 20 neglected tropical diseases that plague over a billion of the world’s poorest people.

As at September 2020, 13 countries had reported that they had eliminated it as a disease of public health concern. Others in Africa were Ghana and Morocco. Togo is pending validation from the World Health Organisation. The organisation has validated the claims of 10 of the 13 countries.

The WHO lists strict guidelines to determine whether trachoma has in fact been eliminated from endemic countries. One is that there must be a system in place to identify and, where necessary, manage any new cases in line with protocols. This means that once a country is confirmed as having eliminated trachoma, a resurgence is not expected.

As we are involved in the ongoing Nigerian effort to curb trachoma, my colleagues and I are studying countries like The Gambia closely for guidance.

Sario Kanyi, the coordinator of The Gambia’s trachoma elimination initiative, said its success started in the community. He added that once people knew what trachoma was, they took charge and helped in communicating what had to be done.

What is trachoma?

Trachoma is an infection caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. It can be spread through physical contact with the eyes, nose or throat of those infected. It can also be picked up from the items used by infected individuals, such as face towels.

Crowded conditions and poor sanitation have been identified as possible enabling factors.

The signs and symptoms of trachoma include: mild itching and irritation of the eyes and eyelids, a discharge of mucus and pus, eyelid swelling and sensitivity to light.

Others are ocular pain, redness of the eye and vision loss. Young children are the most susceptible to trachoma infection. It usually progresses slowly, presenting with more painful symptoms at adulthood.

Repeated episodes of active trachoma can cause the eyelid to be scarred. In some individuals this leads to trachomatous trichiasis, in which the eyelashes turn inward and touch the eye, causing extreme pain. If left untreated it can lead to blindness.

Treating trachoma requires a strategy that integrates four steps known as “SAFE”. The letters stand for surgery (to alleviate eye pain or prevent further complications), antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental sanitation.

The Gambian success story

The Gambia established an eye care programme in 1986. It also initiated policies that helped in combating the condition.

The country mobilised resources through partnerships with local and international specialists, such as the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

A trachoma task force was created under the Gambian National Eye Programme. This was helped by the small size of the country’s population, 2.4 million, which allowed intervention to easily reach most citizens.

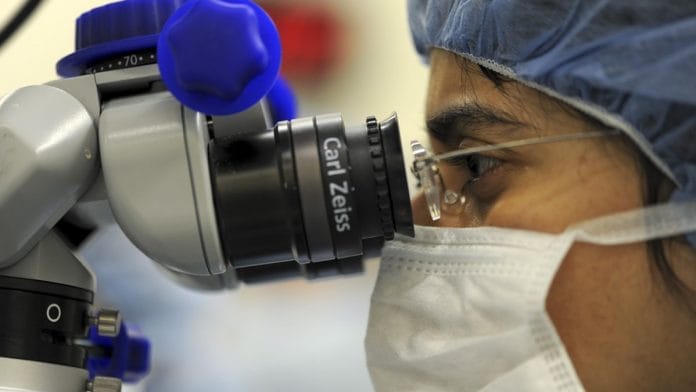

Clinical staff were trained and retrained to deliver surgical procedures to manage the disease. Lid surgeries were then carried out to correct turning in of scarred eyelids and damage to the cornea.

The Gambia undertook campaigns to educate the public on the risks posed by the disease, and about preventive measures like hygiene. Open defecation and proper face and hand hygiene were addressed by building latrines and boreholes for communities.

It also created a network of eye care units across the country with the sole aim of diagnosing and treating people with trachoma. High potency antibiotics were also mass administered to reduce the average bacterial load in the endemic areas of The Gambia.

Thousands of community health volunteers were trained to go from house to house to find people with the disease. The government had support from several NGOs. The Gambia also adhered to the World Health Organisation’s SAFE strategy for eliminating trachoma.

A major component of the SAFE strategy is the mass distribution and administration of Azithromycin. This antibiotic was donated by Pfizer to national programmes that are implementing the trachoma strategy in The Gambia. This led to monitoring of the bacteria load in a community before and after treatment.

Recent studies have been done in The Gambia on measuring the rate of reinfection after mass treatment programmes. The experts do not foresee a reemergence of trachoma in the country even with the risk of infected individuals coming from Senegal to Gambia, where disease is endemic.

The Gambia’s success in eliminating trachoma prevents the occurrence of about 100,000 new cases, saving people pain and possible blindness. It also means that resources previously allocated to combating the disease can now be reallocated to other public health conditions.![]()

Musa Mutali, Lecturer of Optometry, University of Benin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Also read: Doctors in Agra successfully operate on newborn infected with black fungus