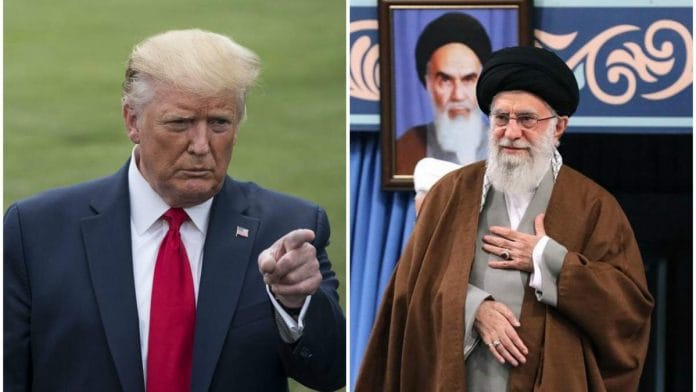

The killing of Qassem Soleimani, commander of the elite Quds force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, in Baghdad takes to a new extreme Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran. The fervent celebrations among U.S foreign policy hawks, and passionate calls for vengeance emanating from Tehran, make it seem that the Islamic revolutionaries have no greater foe than the United States.

A dispassionate view would reveal the opposite: The assassination is the latest and most conclusive evidence that Iranian revolutionaries have no greater friends than their supposed enemies in Washington, D.C.

This pungent historical irony has been verified right from 1953, when the United States overthrew Iran’s elected secular leader, creating the soil in which a religious ideology could flourish. It then watered this soil for decades by supporting a corrupt, inept and brutal despot, the Shah of Iran. The CIA, in particular, helped the Shah’s murderous secret police to create martyrs for the coming revolution.

When the revolution erupted in 1979, the United States, instead of heeding the demand of Iranians, and dumping the hated Shah, chose to mollycoddle him. It was American hospitality to the Shah that provoked hard-line Iranian students to occupy the U.S. embassy in Tehran and take 52 hostages.

The Iranian Revolution was still a fragile affair, with many potential outcomes, when Saddam Hussein invaded Iran in 1980. The urgencies of national consolidation against a vicious and initially successful invader was what empowered Ayatollah Khomeini and other hardliners; they also overturned Khomeini’s deep-rooted Islamic objection to the Shah’s nuclear program.

By choosing to back Saddam Hussein against Iran, the United States played an inadvertently stalwart role in strengthening Islamic revolutionaries during a calamitous eight-year-long war that spawned, among others, the legend of Soleimani.

The U.S. became more directly helpful to Tehran after 9/11. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. military toppled regimes that had long plagued the Iranian regime (Iran had come close to a full-scale invasion of Taliban-ruled Afghanistan before 9/11).

Then, while the U.S. struggled against two lethal counterinsurgencies, Iran expanded its sphere of influence in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Its network of proxies across the Middle East grew even stronger, as Islamic State emerged out of the ruins of the American invasion of Iraq, and the U.S-backed Saudi Arabian assault on Yemen created a strategic opening for closer ties between Iran and Yemen’s Houthi rebels.

More recently, the Islamic revolutionaries were flailing domestically, increasingly reliant on ruthless methods to quell disaffection, before Trump rescued them by killing Soleimani, Iran’s national hero. The U.S has not only managed to unite Iranians behind their present leaders, while effectively delegitimizing and disempowering what had been a growing opposition. Creating the greatest Iranian martyr since Khomeini, it has also refurbished the faded mythology of the Iranian Revolution.

Iran is returning to its nuclear program; its friends in Iraq are more determined to expel American troops from their country. Other fiascos for the United States in a region it once dominated will no doubt follow.

They will confirm something that is as bizarre as it is under-noticed: the recurrent and often extraordinary blindness of American policymakers to the force of anti-colonial nationalism.

Notwithstanding the lofty anti-colonialist pose of President Franklin Roosevelt, they regularly chose to swim against the greatest historical tide of the 20th century: the steady cancellation of the prerogative of a small minority of white men to rule the world in accordance with their interests and wishes. Initial U.S. reluctance to support efforts by Britain, France and the Netherlands — among other European masters of Asia and Africa — to retain their colonies faded before Cold War exigencies. Indeed, in one of history’s better little twists, the Eisenhower administration resisted Britain’s granting of internal self-government to Singapore because it worried that Lee Kwan Yew was a crypto-communist, and launched a CIA effort to subvert the man who would become one of America’s most stalwart allies.

Faced with the truly revolutionary urge for self-determination and sovereignty, the United States has too often supported proxy despots, unleashed its superior military firepower and flexed its diplomatic and economic muscle. But the recourse to brute force is always a sign of lost legitimacy and authority.

Moreover, as James Baldwin once pointed out, “force does not work the way its advocates seem to think it does. It does not, for example, reveal to the victim the strength of his adversary. On the contrary, it reveals the weakness, even the panic of his adversary, and this revelation invests the victim with patience.”

It is with infinite patience — and guile — that Iran’s revolutionaries have reaped the fruits of American blunders. Hemmed in by sanctions, they have still increased their power and influence at the same time that the United States has staged flop shock-and-awe spectacles in the Middle East.

To be sure, Trump’s white-supremacist-friendly regime is only slightly more oblivious to the irrefutable material and intellectual logic of decolonization than some previous U.S. administrations. But as a result of its actions, the U.S. will now be humiliated into a retreat from the Middle East that was long inevitable and should have been voluntarily undertaken, in peace and with dignity. At this stage, Saigon-style departures from the roofs of U.S embassies cannot be ruled out.

Iran, of course, will remain where and what it is: in its own region, as its major power. The death of a military commander is very unlikely to undermine its position. Indeed, as Iran’s leaders confront a morally diminished and self-isolating United States, they can continue to indulge the thought that with enemies such as these, who needs friends.-Bloomberg

Also read: How will Iran respond to killing of Qassem Soleimani? We are about to find out