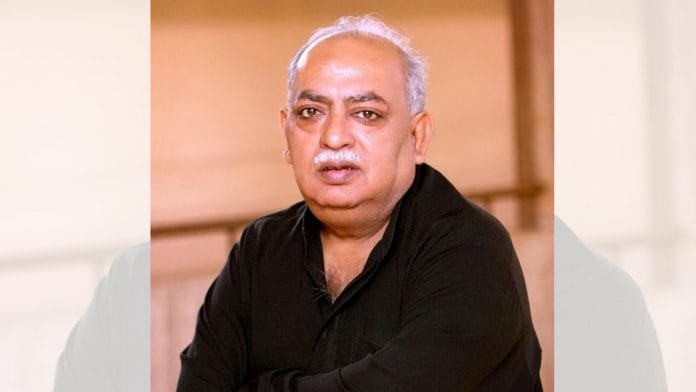

Born in poverty, scarred by Partition, and driven by dissent, Munawwar Rana wrote Urdu the way India speaks — unpolished, intimate, and simple. He made the mother the central figure of his poetry, and insisted that a poet’s first loyalty was to truth, not power, party, or religion. He was a poet who loved fiercely, condemned loudly, and lived and wrote as an Indian before anything else.

Born in 1952 in Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh, this Urdu poet combined Hindi and Awadhi into couplets that celebrated mothers, critiqued power, and bridged religious divides. He grew up in severe poverty after much of his family migrated to Pakistan during Partition. Land was sold, resources vanished, and survival became daily labour. His father worked as a truck driver, often away for days at a stretch. In that absence, Rana’s world revolved around his mother.

Those difficult years deepened his empathy and pulled him closer to his mother. That bond found its expression in Rana’s poem Maa: “Kisi ko ghar mila hisse mein ya kou dukaan aayi, main ghar mein sab se chhota tha mere hisse mein maa aayi (Some received a house, some a shop; I was the youngest at home, and my share was my mother).”

Munawwar Rana’s son, Tabrez, recalled how his father used to say, “My pen is for writing the truth. If I cannot write the truth with it, then it will only be left to put a string in my pyjama, which is not doing justice to my pen.”

Tabrez, also a poet, said he can talk about his father even in his sleep. An autobiography, largely written by Rana himself, is nearing completion with Tabrez putting the finishing touches on it. Rana’s legacy was cut short by throat cancer. He died on 14 January 2024 at the age of 71.

Relationship with power

Rana spent much of his life between cities, ideas, and journeys. For nearly four decades, he lived in Kolkata before moving to Lucknow in the early 2000s. But he kept on travelling constantly for mushairas and poetry. In Kolkata, he found his first-ever teacher in Ezaz Afzal.

He was known for his bluntness, but politics never attracted him as a career or ambition. He spoke only when silence felt dishonest. When journalists or people asked him about events unfolding in the country, he believed it was his responsibility to respond truthfully.

“His relationship with power was distant, almost allergic. He disliked prolonged proximity to politicians and often said that such company made him physically uncomfortable,” said Tabrez Rana.

His life, according to his son, was an open book. There were no cultivated eccentricities or hidden personas. What distinguished him was the language he chose. He stripped Urdu poetry of elitism and brought it closer to everyday speech. That accessibility made him deeply loved by non-Muslim readers and listeners.

In later years, when he spoke critically about his own community or institutions like madrasas, Rana was labelled harsh or controversial. Yet this strictness came from moral consistency, not provocation. He believed that truth does not change based on identity, and anyone willing to critique their own side honestly cannot be reduced to religious labels.

“A person who speaks such words, even if it is bad for his community, it is obvious he is neither a Hindu nor a Muslim — he is a pure Indian,” said Tabrez.

A tough childhood

This idea of being Indian before everything else shaped his poetry as well. Rana often lamented how division had seeped into the most ordinary spaces of life. Courtesy, respect, and shared cultural language mattered deeply to him. He believed that between greetings like namaste and assalam walekum, adab stood in the middle — where none is insulted, and no one feels threatened.

As a child, there were nights when he and his siblings went to bed hungry, with only utensils filled with water by their mother to help them imagine a meal before sleep. Rana, older and more observant than his siblings, noticed these silences. He watched his mother’s simplicity and sacrifices closely.

“Instead of the traditional beloved, he made the mother the emotional centre of his verse. Loss, protection, and unconditional love found their form in her presence,” said Tabrez.

Rana’s creative journey had begun much earlier, shaped by thought. Poetry, for him, was not born overnight; it emerged from how one sees the world. Whether one notices flowers at a traffic signal or the child selling them reveals the poet’s mind.

That sensitivity grew out of struggle. He read, wrote, refined his voice, and eventually reached Lucknow’s literary circles. At that time, he was still known as Munawwar Ali Aatish. It was poet Wali Asi Sahib who advised him to abandon that pen name. Learning that his family ran the Rana Transport Company, Wali Asi suggested a new identity — Munawwar Rana.

Also read: From Rashid un-Nisa to Anandibai Joshi, how women shaped India’s literary history

Controversies

The poet’s life took many twists and turns, and personal struggles remained: nights marked by alcohol, family disputes over property, and even a staged shootout involving his son Tabrez. Amid this, simple pleasures like flying kites and listening to classical music kept him at home.

Controversies, including a family property dispute in 2021, were deeply exaggerated, according to his son.

“Disagreements existed, as they do in every household, but they were magnified by media narratives and political targeting,” said Tabrez.

In 2015, Rana returned his Sahitya Akademi award to protest rising intolerance, sparking a media storm. When falsely linked to a couplet on the 2015 Dadri lynching case, he proved his innocence, living the defiance he wrote about in his shers. His later years were marked by controversies: justifying French teacher Samuel Paty’s killing over alleged blasphemy, accusing former CJI Ranjan Gogoi of selling himself to deliver the Ayodhya verdict as ‘sold justice’, and making provocative comparisons that drew legal cases.

Even a poetic tweet during the farmers’ protests stirred uproar. These acts, from challenging labels like ‘Taliban’ to calling out ministers, made him a fearless voice.

“A poet holding a pen was painted as something far more sinister, while far greater wrongs elsewhere were ignored,” said Tabrez.

Throat cancer took him at the Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences in Lucknow in 2024, yet leaders from Narendra Modi to Akhilesh Yadav and Javed Akhtar mourned him, and thousands attended his funeral — a tribute to a poet who lived fully, boldly, and on his own terms.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)