In Khushwant Singh’s last novel, three old men—a Sikh, a Hindu Punjabi, and a Pathan—meet every evening on the ‘Boorha Binch’ at Delhi’s Lodhi Gardens. The eminent journalist and author confessed in the book, The Sunset Club (2010), to having mixed fact with fiction. This makes his fictional counterpart, Sardar Boota Singh, especially revealing in terms of how the author saw himself—a “Rangeela Sardar” fond of swearing, salacious stories, and risque humour.

One of the earliest Indian writers to speak freely of sexuality, Singh earned notoriety as the “dirty old man” of Indian journalism—a title that didn’t bother him in the least. Singh didn’t see himself as an aberration, but merely more transparent than the average Indian.

“We Indians are full of contradictions: we preach peace to the world and prepare for war. We preach purity of mind, chastity and the virtues of celibacy; we are also obsessed with sex. That makes us interesting,” Singh wrote in The Sunset Club.

He is everywhere in the book—in the narration of the history of the Lodhi Gardens, his scathing remarks on politicians and religious fundamentalists, and even his love for nature. What is new is his struggles with mortality.

The author was 95 when he wrote The Sunset Club. He poured the ailments of his age into Boota Singh with the same honesty that accompanied all his writing: The character suffers from diabetes and blood pressure problems, and spends a great deal of time complaining about the medicines he must take.

For all its reverie and depth, however, Singh also imbued The Sunset Club with surprising vitality, partly through his trademark raunchiness. When Boota Singh’s friends die by the end of the story, he doesn’t allow himself to wallow in despondency. He returns to Lodhi Gardens, sits on the now-unoccupied Boorha Binch, and muses on the “feminine charm” of the Bara Gumbad (Big Dome).

“Boota returns to gazing at the Bara Gumbad. It does resemble the fully rounded bosom of a young woman.” (The Sunset Club).

Also read: A new ‘Train to Pakistan’ play asks—freedom for whom and from what?

Fearless critic

Author Kishwar Desai remembers Singh for more than his notoriety.

“I remember Khushwant Singh as an extremely kind person—someone who was very, very interested in the people around him. Quite unlike the image that he had created of himself… He was extremely serious about everything,” Desai told ThePrint.

When she met Singh, Desai was working on a series of documentaries on Punjab, including one on Maharaja Ranjit Singh. “Singh was full of information,” she said. “Not only that, he was very keen to help us in the process.”

Desai eventually filmed a documentary on Singh for the now-defunct BiTV channel. It captured his vitality, featuring him playing tennis and swimming. Singh was over 80 years old at the time.

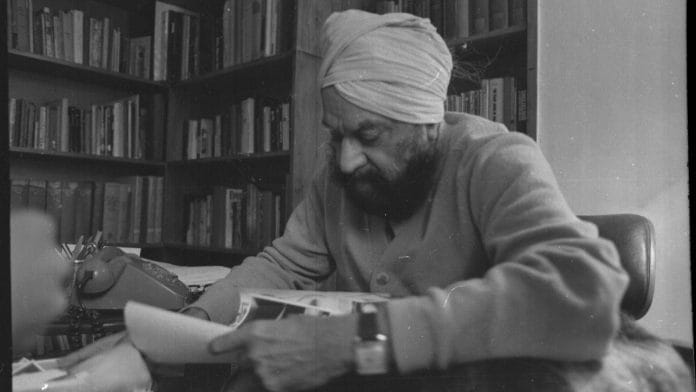

Age didn’t dull Khushwant Singh’s pen. In his column, With Malice Towards One and All, Singh continued to attack fundamentalists and criticise politicians, which often earned him hate mail—but didn’t upset him. He kept writing the columns until shortly before his death on 20 March 2014.

Singh was one of India’s most important cultural exports to the West. For Desai, his contribution to literature was even more significant.

“He was able to add to the world of literature in a manner that very few authors do, which is to encourage young authors. He was my first mentor. He believed in what I was doing before I’d written a single book. And I know that he did that for many, many other people.”

Train to Pakistan

Khushwant Singh was born in 1915 in Punjab’s Hadali village (now in Pakistan). In 1939, he established his practice as a lawyer in Lahore. Eight years later, the writer witnessed the horrors of the Partition firsthand and was forced to uproot his family from Lahore.

In his autobiography, Truth, Love & a Little Malice (2002), he wrote about his experience of reaching Delhi a few days before the declaration of India’s Independence.

“The magnitude of the tragedy that had taken place was temporarily drowned in the euphoria of the Independence to come. It was like a person who feels no hurt when his arm or leg is suddenly cut off: the pain comes after some time,” he wrote.

Singh shaped his experiences into his most significant novel, Train to Pakistan, in 1956. According to Desai, who founded the Partition Museum in Delhi, a huge silence had grown around the Partition at the time. Almost a decade after the violence, people wanted to cover it all up so they could avoid the tension altogether.

“He was courageous to have written this novel, which puts it all in front of us—the divisions, the difficulties,” Desai said.

Years after the Partition, as the wounds healed on both sides of the border, Khushwant Singh visited his birthplace, Hadali village in Pakistan. He was welcomed with flowers and fireworks. Pakistani journalist and politician Jugnu Mohsin found the composite culture of India and Pakistan in Singh.

“Khushwant Singh was a son of both India and Pakistan. In his person, you saw what we could have been, had all of these unfortunate incidents not taken place, which have left us all with enormous burdens.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

The only reason Khushwant Singh was celebrated was because he was a Punjabi writing in the English language – a rarity and a novelty. No wonder, sentimental Delhiwalas adored him and showered affection. Truth is, he was a pretty average writer. Though he tried very hard to achieve greatness. Hardly any of his works can be considered a masterpiece and again pretty much nobody knows or reads him outside Delhi.

One would be hard pressed to name even three Punjabi English authors even in today’s age.

If someone is serious about Indian English literature, then he has to look at Bengal and South India. These two regions have a stellar cast of writers in the English language. Together, they have shaped Indian writing in English and given it stature and respectability even in the West.