New Delhi: A tense moment on the set of Mughal-e-Azam in 1953 nearly derailed one of Indian cinema’s greatest masterpieces. Dilip Kumar refused to refer to Anarkali, played by Madhubala, as a nacheez laundi—a lowly courtesan—as the script called for. Shooting came to a halt. He was adamant that such derogatory language was beneath a royal character.

But director K Asif stood his ground. He had no intention of changing a single word of the script. It was the work of Kamal Amrohi, the master dialogue writer who had introduced the poetic Urdu of the royals into Bollywood, wrote journalist Anitaa Padhye in her 2020 book, Ten Classics.

Asif called Amrohi on set. He, too, refused to amend the line. For him, the dialogue perfectly encapsulated a royal man’s intense anger, delivered in the harshest, most colloquial terms.

Dilip Kumar begrudgingly agreed. When the film finally released in 1960, it was a hit. Mughal-e-Azam won the Filmfare Award for Best Film, and Amrohi took home the Best Dialogue Award.

“After that, whenever anyone spoke of Kamal Amrohi in (Dilip Kumar’s) presence, he would say, ‘Urdu to Kamal Amrohi ke zubaan ki laundi hai’ [Urdu is Kamal Amrohi’s beloved],” wrote Padhye

“It was Amrohi’s dialogues, his literary and poetic touch, that gave Mughal-e-Azam its immortal quality,” film critic Pradeep Sardana told ThePrint.

Amrohi crafted career-defining roles for actors like Madhubala and Meena Kumari. “His work was a grand fusion of history, poetry, and cinematic brilliance,” he added.

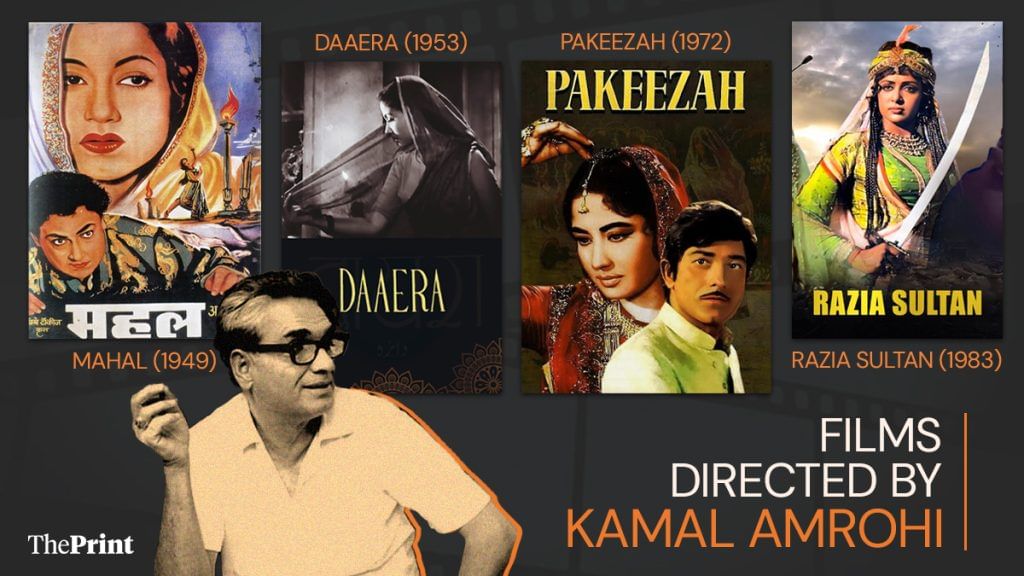

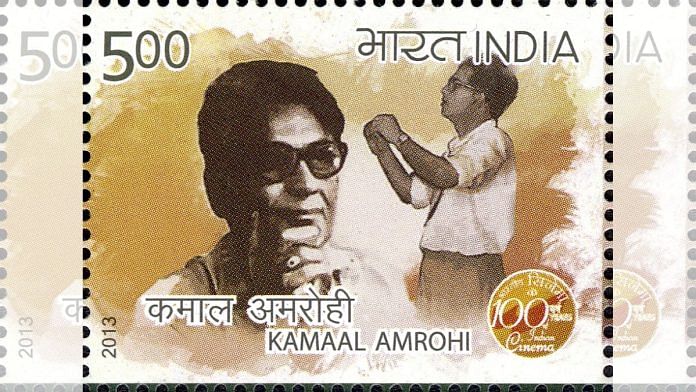

This was Kamal Amrohi’s legacy. He’s the man behind Bollywood’s grandest stories— Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah, Razia Sultana. He directed only four films, but his penmanship, screenplays and dialogues defined the contours of Bollywood.

Also read: MN Nambiar, Tamil cinema’s most convincing villain wielded swords with MGR, worshipped Ayyappa

A creative genius

Born on 17 January 1917, in Amroha, Uttar Pradesh, Kamal Amrohi came from a wealthy landowning family. But the talkies captured his imagination. At 16, he ran away from home, and went to Lahore before eventually making his way to Bombay in the early 1930s. It was the legendary singer-actor KL Saigal who first recognised Amrohi’s potential and encouraged him to move to Bombay, Sardana recalled.

Saigal helped him find a place at Sohrab Modi’s Minerva Movietone studio, where Amrohi’s first major success, Jailor (1938), was written. However, it was his directorial debut, Mahal (1949), that cemented his position as a filmmaker.

Blending elements of gothic horror with reincarnation, Mahal became a genre-defining film and launched the careers of both Madhubala and Lata Mangeshkar. Its haunting atmosphere, eerie lighting, and cinematic references to German expressionism showcased Amrohi’s craftsmanship.

“People say it was that song [Aayega Aanewala] that made Lata ji so popular. I believe Mahal was also known because of this song. Lata ji was my father’s favourite singer and she sang for him right till Paakezah and then Razia Sultan, where she again gave us the haunting Aye Dil-e Nadaan,” Amrohi’s son Tajdar Amrohi noted in a 2022 interview.

Amrohi’s creative genius was matched only by his uncompromising nature. A perfectionist of the highest order, he had a reputation for demanding nothing less than absolute precision from everyone on his sets.

“All his movies to date, in spite of the lack of probability, their purple prose, their hideous opulence and ethereal imagery, have a certain surviving magic in them,” journalist Sunil Sethi wrote in a 1981 India Today article.

Also read: Laxmikant Berde could never break out of the comedy mould. The audience kept him trapped

An all-consuming love

While Mughal-e-Azam was undoubtedly grand, it was Pakeezah (1972) that truly encapsulated Amrohi’s legacy. A slow-burning epic, Pakeezah took almost 14 years to complete. It was also a poignant reflection of Amrohi’s own life–a tale that mirrored the tumultuous relationship with Meena Kumari whom he eloped with in 1952.

“Other Indian popular films may be subtler but few have quite the force and romantic conviction of Amrohi’s. He never struck gold again, and nor did Kumari, whose last film this was. But gold Pakeezah definitely is,” Derek Malcolm wrote in a 1991 Guardian review.

Their marriage, filled with passion, possessiveness, and ego clashes, became the source of constant strain.

In 1963, when at a film event, filmmaker Sohrab Modi introduced the couple to the Governor of Maharashtra, saying, “This is Meena Kumari, and this is her husband Kamal Amrohi”, Amrohi corrected him: “No, I am Kamal Amrohi, and this is my wife, the renowned actress Meena Kumari.” He then turned and walked out, leaving Meena Kumari alone.

This moment, Sardana recalled, encapsulated Amrohi—in his complex marriage to one of cinema’s greatest actresses, Amrohi remained determined to be remembered as more than “Meena Kumari’s husband.”

His legacy, defined by his films, went beyond his real-life tragic love story.

“India will never see another director as meticulous as he is,” RD Mathur, a senior cameraman who worked on Mughal-e-Azam and Razia Sultan once noted.

For one of Amrohi’s assistants, who spent half his life working with him, “he is the last Moghul. Nothing can move in the unit without his command.”

“Kamal Sahib’s movies are a one-man show. He controls everyone and everything himself. He hands out his film as a personal gift to each member of the audience. It’s his way of saying, thank you for coming to see my movie,” Sethi wrote.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

The Urdu language and Urdu authors/poets are grossly overrated. Maybe this stems from the inferiority complex of the Hindi-belt residents. Because, here in Assam, nobody considers Urdu even a respected language. I believe the same applies for Bengal, Odisha, Maharashtra and other states. It’s just the Hindi-speaking states which hype up Urdu.