New Delhi: Had it not been for the fourth Guru of Sikhism, perhaps Amritsar wouldn’t have been born. The city’s bustling markets and the gentle pool surrounding the Golden Temple all came together when Guru Ram Das invited merchants and artisans from other parts of India to settle in this new town with him.

A son-in-law of the third Guru, Amar Das, Ram Das also strengthened the institution of langar (community kitchen) and manjis (missionary centres) in attempts to consolidate the foundations of a minority Sikh community in the face of powerful Mughal politics and hegemonic Brahminical traditions.

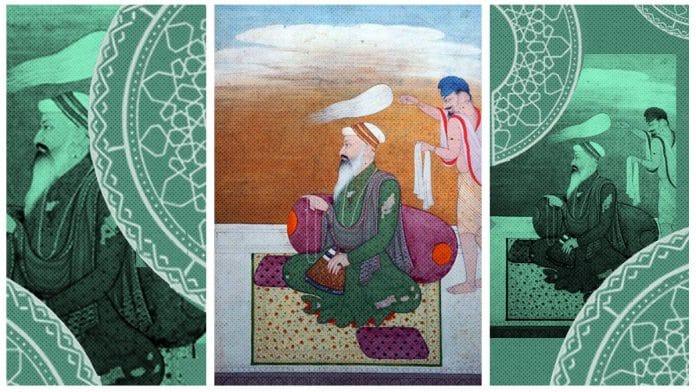

On his birth anniversary, here is a look at Ram Das’ fascinating life, his defence of egalitarian Sikhism at Mughal emperor Akbar’s court and contributions to the traditions of the Anand Karaj.

In defence of egalitarianism

Born as Bhai Jetha on 9 October 1534 — according to the Nanakshahi calendar — in Lahore, he lost his parents at the age of seven and was brought up by his grandmother, who later took him to Goindval in Punjab’s Tarn Taran district. It was here that he met Guru Amar Das and decided to become the latter’s disciple. He quickly rose in the ranks to emerge as his Guru’s favourite, and even married the latter’s younger daughter — Bibi Bhani — and eventually, was appointed Ram Das, the fourth Guru of the Sikhs.

His bani, or set of songs, contained more than 600 hymns that held various teachings for followers of the faith. But his teachings went far beyond the books. When a group of Brahmins in Goindval raised objections to langar — that ostensibly ignored distinctions of the four castes — Amar Das dispatched his son-in-law to meet Emperor Akbar and address the grievances. Ram Das’s strikingly simple statement at the royal court, that all were equal in the eyes of god, led Akbar to dismiss all objections.

In the years to come, Ram Das also stepped up efforts to strengthen the practice of commensality and even proclaimed that “kings and emperors are all created by God; they come and bow in reverence to God’s humble servant”.

But the man had to leave Goindval soon after his coronation in 1574 when he was faced with rivalry from Amar Das’ sons. As advised by his father-in-law, Ram Das and Bibi Bhani then moved to a new place.

An ‘autonomous’ Amritsar

It is this new place, the chief feature of which was its human-made sarovar (tank), that was to become Amritsar in the years to come. Guru Ram Das had laid the foundations of Ramdaspur, later renamed to Amritsar, when he inaugurated the pool’s excavation in 1577.

The sarovar later became the nucleus of Amritsar when Ram Das’ youngest son and successor, Guru Arjan Dev, built a temple complex around it and placed a copy of the Adi Granth at Harmandir Sahib in 1604.

Ramdaspur or Amritsar was also perhaps one of those few towns that remained autonomous in the context of a larger Mughal rule. Arjan Dev’s proclamation that the town had no collector of taxes was a testimony to this fact. He had pointed toward a reality that the town was under the “authority of the Guru, not the Mughal state”.

Charting roadmap for a marriage law

Among Guru Ram Das’s most famous compositions, the most well-known is his wedding hymn that formed the basis of the Sikh wedding ceremony called Anand Karaj. This ceremony is centered on the laavaan — four stanzas that the fourth Guru had composed. The hymn also emerged to be the focal point on which the British-era Anand Marriage Act of 1909 was later formed.

In the years after Independence, however, the Act garnered controversy when Sikh marriages were brought under the fold of the Hindu Marriage Act. After years of protests, in 2012, several states, including Delhi, decided to allow Sikhs to register their marriages under the Anand Marriage Act.