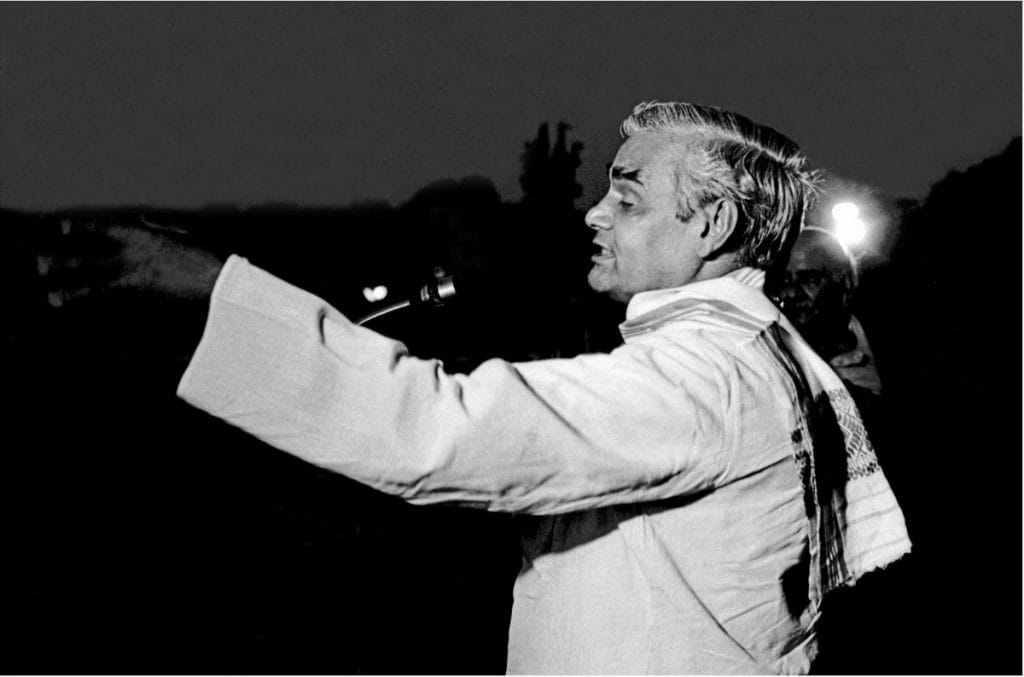

The yellow two-seater airplane was relentless. It circled Delhi’s Boat Club 23 times, scattering Congress leaflets over the grounds where Atal Bihari Vajpayee was addressing government employees during a rally for the 1971 general elections. “Is this democracy?” he reportedly asked in disgust.

Then a two-term Lok Sabha MP from the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, he was already making the Congress nervous. The plane sorties were the young Rajiv Gandhi’s idea, writes Abhishek Choudhary in Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right, 1924–1977. Vajpayee’s invoking of democracy in the face of challenges would become familiar, whether in his 1996 address after losing the vote of confidence or in his 2004 concession speech.

He did so, for the most part, with purpose, clarity of thought, and an infamous penchant for unusually long pregnant pauses. But he was also a man of contradictions. Rabble-rouser by day, consensus-builder by night; hawk one moment, dove the next; tender with one, politically deft with another; guarded in person, vulnerable in public.

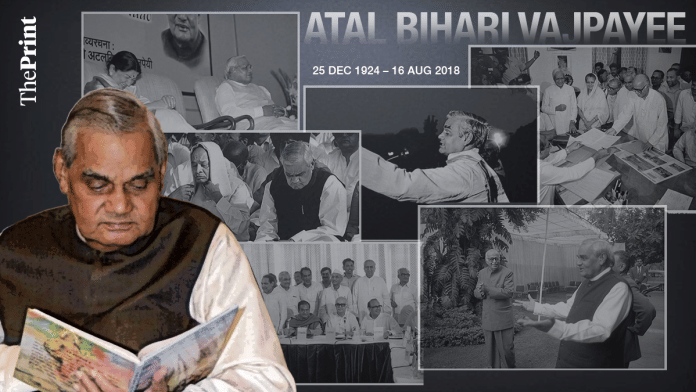

Across his five decades in politics, he was elected to the Lok Sabha 10 times, the Rajya Sabha twice, and served as Prime Minister in two truncated stints and one unbroken term of six years and two months. He retired from public life in 2009, not long after a stroke took away what he valued most — his voice. It was one that had rung out across public meetings and Parliament from the formative years of the country.

Vajpayee died on 16 August 2018 at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, aged 93, leaving no biological heirs and a political legacy that continues to be contested. It’s something he himself has alluded to in good humour.

“During the course of this debate a remark has been made repeatedly, that personally Vajpayee is a good leader but his party is not good,” he joked in his speech on the confidence motion on 28 May 1996, just before his 13-day government fell.

This barb is often attributed to Khushwant Singh who is said to have once remarked: “Vajpayee is the right man in the wrong party.”

Lauded as he was for his democratic instinct, it’s not as if Vajpayee did not have his blind spots. His incendiary 1983 speech about ‘foreigners’ in Assam, delivered shortly before the Nellie massacre, is often linked to the violence. His insistence on dangling the carrot and not the ‘big stick’ before those calling the shots in Islamabad or Rawalpindi was also criticised. Yet through it all, he was able to gain admirers from across the political spectrum through his intellectual engagement. He returned, again and again, to dialogue and reconciliation.

“Despite his RSS roots and continuing association with the Sangh Parivar, I think he is a good, if not a better Prime Minister than any we have had,” Khushwant Singh once wrote. “I am not so sure of his stature as a poet.”

Also Read: Limits on nuclear programme today will tie our hands in future: Vajpayee on India-US deal

Middle path or see-saw?

Vajpayee wore many hats: journalist, poet, swayamsevak, parliamentarian, Leader of the Opposition, Prime Minister. But the most enduring of these was that of a political moderate navigating a party often defined by its extremes.

A day before the Babri Masjid was demolished, he thundered at a Lucknow rally: “There are sharp stones there. The ground needs to be levelled.” But afterwards, he expressed his regret: “What happened in Ayodhya on the 6th was very unfortunate. It should not have happened.”

Born on 25 December 1924 into a family that had migrated from Uttar Pradesh’s Bateshwar to Gwalior where his father was a schoolteacher, Vajpayee was part of the reason why the BJP was called a ‘cow belt’ party. It’s a term he resented deeply.

“How can you deride us by saying we are the cow belt party,” he once said. “We have won in Haryana, we got support in Karnataka…”

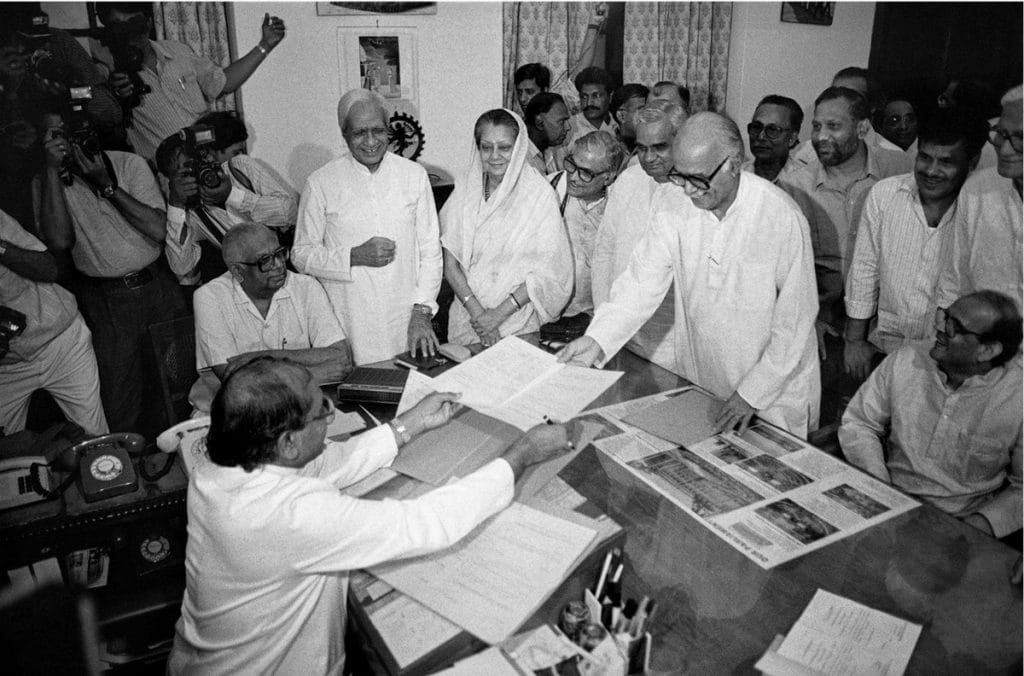

First elected to the Lok Sabha in 1957, Vajpayee lost in 1962, returned to Parliament through the Rajya Sabha, and reclaimed his Balrampur seat in 1967. The next year, he became president of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. A decade later, he was India’s External Affairs Minister in the country’s first non-Congress government, at the age of 53.

But Vajpayee’s ascension thereafter was gradual and gruelling. He was relegated to the Opposition benches in 1979 when the Janata Party splintered, and Indira Gandhi returned to power.

The Bharatiya Janata Party was born the next year and Vajpayee became one of its most prominent faces. A founding member who offered both ideological ballast and political legitimacy.

The millions of Indians whose aspirations he represented throughout his 52 years in public service saw him as the one renegotiating the social contract on their behalf. But there have always been strong critical voices.

Could he have done more to prevent the Babri demolition? Or the 2002 riots in Gujarat? Could his government have handled the IC-814 hijack better? Should he have declared war on Pakistan after the 2001 Parliament terror attack? These questions continue to frame debates about his tenure, with ideology often dictating the answers.

But there is also a small trove of biographies — by Abhishek Choudhary, Vinay Sitapati, Neerja Chowdhury, Sagarika Ghose, NP Ullekh, and Kingshuk Nag — that converge on a couple of recurring conclusions. An imperfect leader who searched for the middle path even if it meant taking apparently contradictory stands at times.

“Vajpayee turned out to be different from very nearly all other major Sangh Parivar figures of his generation,” Abhishek Choudhary told ThePrint. “Partly because he had the temperament of a free bird and partly because he was lucky to get far greater exposure than anyone else in the saffron brotherhood.”

By the time Vajpayee became the Janata foreign minister, he had already travelled to 16 countries, according to Choudhary.

“Mind you, this was a time when none of the three RSS chiefs had ever travelled abroad,” he added.

Also Read: Vajpayee’s ‘insaniyat’ remark wasn’t one-off, his team worked on Kashmir for years

Hawk one moment, dove the next

Well before he became PM for the first time, the “early Vajpayee was far more critical to the Sangh parivar’s project of Hinduizing India than is universally believed,” wrote Choudhary in his two-part biography.

Even as he helped propagate that ideological project, Vajpayee also worked to contain its excesses.

“Senior party leaders, including Vajpayee, worked out for party consideration a formula barring the membership of anyone who espoused a theocratic state,” note Walter Andersen and Shridhar Damle in their book The Brotherhood in Saffron. This was in the backdrop of the ‘double membership’ crisis over whether members of the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government could also belong to the RSS—an issue that became the undoing of the dispensation in 1979.

Senior journalist Neerja Chowdhury described Vajpayee to ThePrint as a “middle-of-the-roader in a very diverse country, which he realised could only be run by consensus through moderation.”

As early as August 1979, Vajpayee had written in The Indian Express, exhorting the RSS to clarify that by “Hindu Rashtra” it meant “the Indian nation which included non-Hindus as members.” In 1996, he reaffirmed this position in the Lok Sabha during his pre-resignation speech.

“The BJP does not stand for uniformity,” he said. “We recognise India’s multi-religious, multi-lingual and multi-ethnic character.”

It was this double role — within and yet slightly apart from the Sangh — that prompted former RSS ideologue KN Govindacharya to call him a “mukhota”, a moderate mask fronting for hardliners, though he denied it later.

“What is fascinating about Vajpayee is how he straddled these contradictions. He was a moderate in a Right-wing Hindu party, and he managed to keep that image all through, right from the 50s,” added Neerja Chowdhury.

Not just ideology, Vajpayee also had a shifting stance on nuclear capability, which Chowdhury recorded in her book How Prime Ministers Decide.

“In the 1950s, he was a pacifist. In the 1960s, he became a hawk, in line with his party’s position that India needed to acquire nuclear weapons. In the 1970s, he was back to becoming a dove,” she wrote.

Vajpayee shed his credentials as a dove for good on 11 May 1998, when he declared at a press conference that India had conducted three underground nuclear tests that day — a fission device, a low-yield device, and a thermonuclear bomb (hydrogen bomb).

Chowdhury described him as “the peaceable Prime Minister who roared”.

Yet Vajpayee would later cede credit in great measure to PV Narasimha Rao, calling him the “true father” of India’s nuclear programme after the former Prime Minister’s death in 2004.

Since it was Rao who banned RSS in the immediate aftermath of the Babri demolition, the statement was unexpected from Vajpayee who was cultivated in the ‘anti-Congress’ nursery of the Sangh.

It wasn’t the first time though. When his opinion was sought on whether Indira Gandhi, declared guilty of ‘serious breach of privilege and contempt’ of Parliament, be punished severely or not, Vajpayee suggested a ‘reprimand’ would be enough. This was documented by former President Pranab Mukherjee, a career Congressman, in the first instalment of his four-part autobiography.

Former defence minister Sharad Pawar also sheds light on this side of Vajpayee in his autobiography.

“Atal ji discarded partisanship and took the decisions purely on merit,” he wrote on meetings to appoint a CBI director, which Pawar attended as Leader of the Opposition.

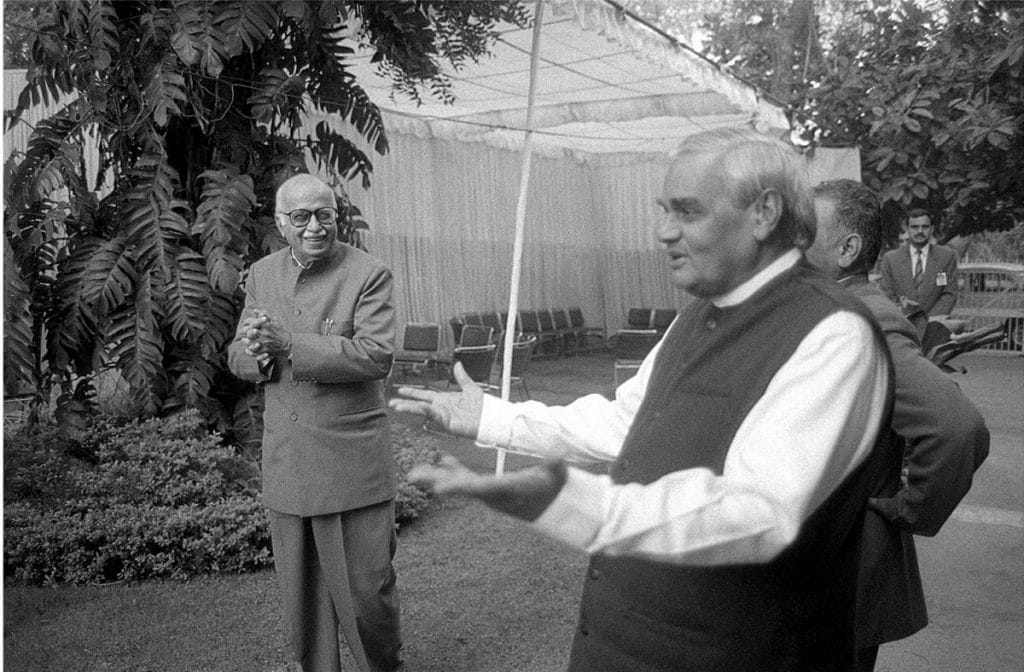

Even on economic policy, the contradictions were visible. He had once railed against Indira Gandhi’s nationalisation spree under the banner of ‘Garibi Hatao’. But when the BJP was formed in 1980, he and LK Advani picked ‘Gandhian Socialism’ as its guiding mantra.

Jan Sangh’s economics were never fully coherent, shifting with political needs, according to Abhishek Choudhary.

“It rejected Congress-style socialism in rhetoric, favouring decentralised ownership, encouragement of small traders, and opposition to large-scale state control. Yet it accepted state planning in principle, endorsed protectionism, and avoided firm commitments on land reforms (and in fact vociferously opposed land reforms in private),” he said. “Its leaders often took contradictory positions so that, depending on circumstances, the party could plausibly argue both for and against every economic measure.”

On Pakistan, too, Vajpayee’s position evolved. In February 1999, he boarded a bus to Lahore, making him the first Indian Prime Minister to visit Pakistan in a decade. Just three months later, the Kargil conflict broke out. And Vajpayee, a peacenik for much of his life, proved himself a wartime Prime Minister to reckon with. His popularity shot up and the NDA won the 1999 elections decisively.

That was the essence of Atal Bihari Vajpayee. He was, much like Homer’s Odysseus, “the man of twists and turns, driven time and again off course… Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds, many pains he suffered.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)