New Delhi: In the summer of 1978, while travelling through Europe, Babasaheb Purandare watched grand Roman ballets in open-air theatres. He was struck by their scale, drama, and immersive power. For a person who was solely “preoccupied” by Shivaji, the experience stayed with him.

Days later, in a letter from London to his collaborator Diwakar Pande, he wrote of a vision: a historical spectacle on the life of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, staged with the same grandeur and theatricality.

That vision became Janata Raja, an epic play that over the next four decades, would enthrall audiences across India with its powerful dramatisation of one of India’s most revered warrior kings.

Forty-one years since its premiere in 1984, and more than 1,550 shows later, the play stands as a towering cultural achievement. In 2015, Janata Raja also premiered in the same place it was conceived — London.

But as a historian, author, and playwright devoted to Shivaji’s legacy — and perhaps because of it — Purandare’s accounts of the Maratha king were not accepted by everyone. His critics accused him of being a Brahmanical interpreter of history.

He also faced sharp criticism from writer Bhalchandra Nemade, the Sambhaji Brigade, and NCP leaders Jitendra Awhad and Udayanraje Bhosale, who accused him of distorting history.

A ‘myopic view’

Purandare was often called Shiv Shahir or Shivaji’s bard–and with good reason, too. Most of his work was dedicated to Shivaji. This includes a tw0-volume biography, Raje Shichhatrapati.

Purandare’s staunchest defenders came from parties like the Shiv Sena and the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS). Amid protests by Sambhaji Brigade over giving him the Maharashtra Bhushan award in 2015, MNS chief Raj Thackeray hit back, accusing them and parties like the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) of fuelling caste divisions in the state.

However, for those who knew him, Purandare was the man who was solely preoccupied with Shivaji, without caring much about his critics.

“Babasaheb took the life of Shivaji Maharaj to the most common people in an easy-to-understand and vivid language, but he never lost sight of the fact that history research is a science. He displayed the openness of mind to study new material and incorporate it in his writings provided it was based on facts and solid proof,” humorist PL Deshpande wrote in his pen sketch on Purandare in the book Gangot.

That said, not everyone agreed with this view. Historian Jaswandi Wamburkar told ThePrint that while Purandare did play a crucial role in “democratising Shivaji’s history and bringing it to households”, he projected a “pro-Brahmin, anti-Muslim Shivaji”, a depiction she does not agree with.

“As a child, I used to watch his plays and believe all that was depicted. His shows had a tremendous impact in Maharashtra. But as you research more, you realise his lens was myopic. He gives undue credit to Dadoji Konddev [Shivaji’s tutor] and played into caste politics.”

She added, “Some scholars argue that his portrayal of Shivaji Maharaj as a staunch protector of cows and a pro-Brahmin figure (go-Brahman pratipalak) deviates from historical reality. Similarly, his depiction of Shivaji Maharaj as being inherently opposed to Muslims has been challenged, with critics asserting that such interpretations misrepresent the inclusive and strategic nature of his leadership.”

Also read: Mangala Narlikar changed how girls in India learn math. She took the fear out of it

The man who could visualise Shivaji

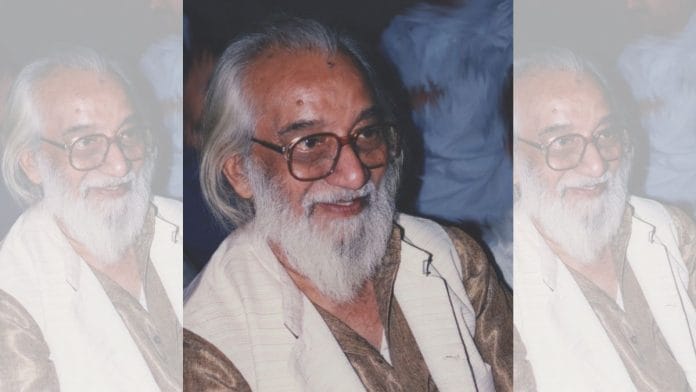

Born Balwant Moreshwar Purandare on 29 July 1922, in Saswad, Pune, Purandare’s interest in Shivaji was born out of long walks up the hill with his father who would narrate tales of the Maratha Empire.

“For the next decades, that became the sole preoccupation of his life,” humorist Deshpande wrote in Gangot.

Purandare was not only a historian, but also a poet, novelist, orator, and playwright. For decades, he trekked through Maharashtra, visiting nearly every fort Shivaji had conquered, gathering oral histories, collecting manuscripts, weapons, and artefacts, and preserving them with deep personal care.

He authored over 36 books — including Gadkot Kille, Shelar Khind, Agra, Rajgad, Purandar, Pratapgad, Savitri, and Fulwanti — with each delving into different facets of Shivaji’s journey and the geography of the Maratha Empire. However, his work was not bereft of criticism and made headlines in 2015 when the Maharashtra government decided to confer the Maharashtra Bhushan award on him.

The controversy dates back to 2003 when American scholar James W Laine credited Purandare’s writings as a key source for his book Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India. The book, published in 2003, included speculative and widely denounced claims about Shivaji’s mother, Jijabai. Furious backlash followed, leading to a violent attack on Pune’s Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) by Sambhaji Brigade activists in January 2004 and a statewide ban on the book.

Many objected to Laine’s lines in the book where he noted that some Maharashtrians joke that Shivaji’s true father was not Shahaji, but his Brahmin tutor Dadoji Konddev. Purandare was among the critics.

Laine later also clarified that he had not borrowed from Purandare’s books. However, the damage was done. NCP president Sharad Pawar later acknowledged that his criticism of Purandare stemmed from the historian’s association with Laine.

Unfazed by critics, Purandare continued to lecture, write, and tour the state, captivating audiences with his commanding oratory skills and deep reverence for Shivaji Maharaj. In 2019, the Government of India recognised his towering contributions with the Padma Vibhushan, the country’s second-highest civilian honour.

“One needs to be obsessed with history if one wants to understand it,” he once said at a felicitation on his 99th birthday, three months before he passed away in November 2021. “I love Shivaji Maharaj, but I am not his pujari or his ghulam. I am enamoured with his intellect, bravery, and wisdom. But most of all, I am in awe of his idea of nation-building.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)