New Delhi: Gogi Saroj Pal never had much time for the neat labels of a gallery catalogue, including ‘feminist artist’. She called herself a “different type of cocktail”. Across nearly five decades, she created bold, idiosyncratic paintings of women on her own terms, with a contrarian streak running through both her canvases and her conversation.

“I think my path is the path of Gogi, I am me,” she said in a candid interview to Art Life Gallery, a few years before her death at the age of 78 on 27 January 2024. “Whether people like it or not, do what you want. Log burai karein toh aur karo”—if people criticise something, do more of it.

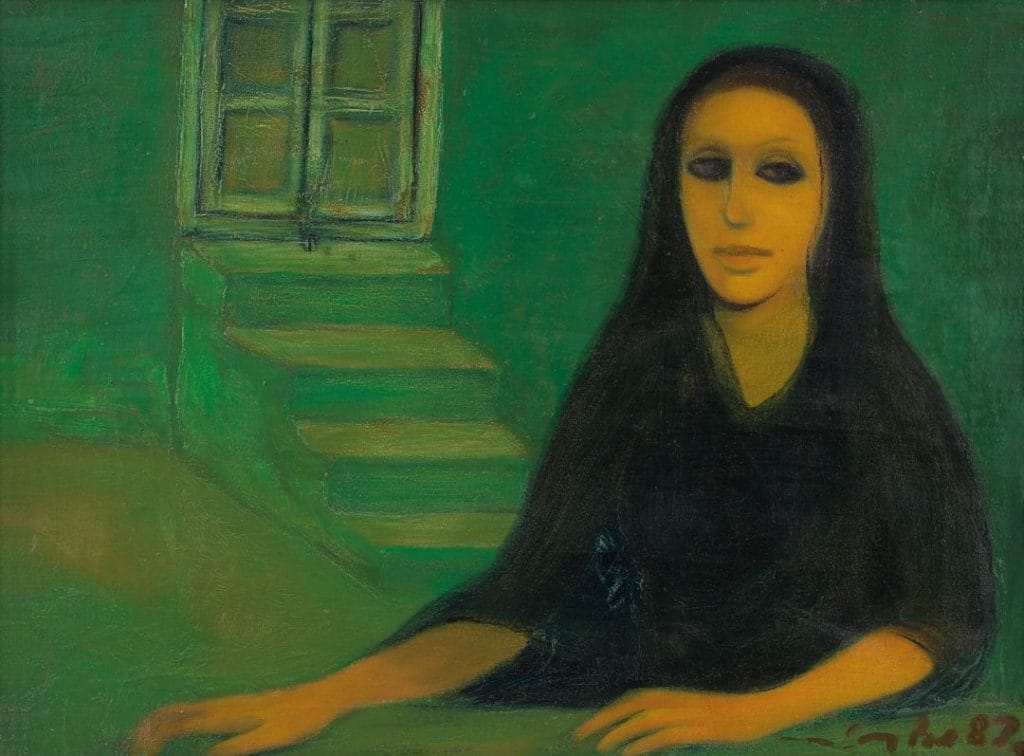

Often hailed as a pioneering feminist painter, Pal returned repeatedly to themes of othering, marginalisation, desire, and women’s self-awareness. She drew irreverently from mythology and other painting traditions as well.

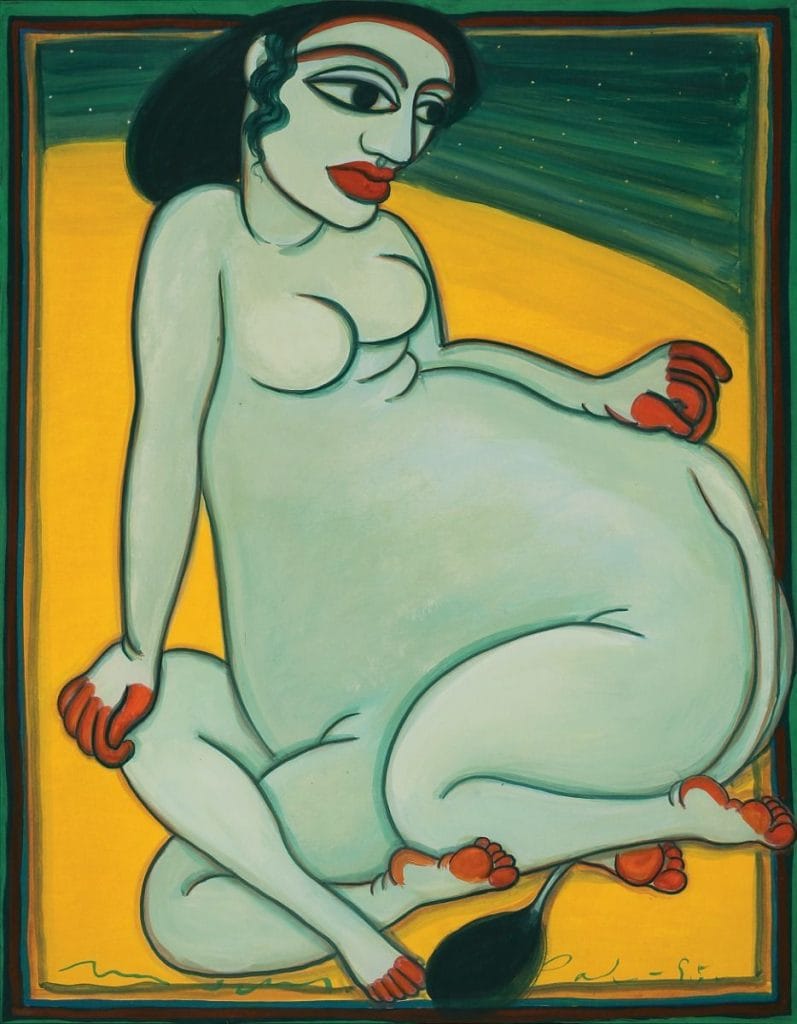

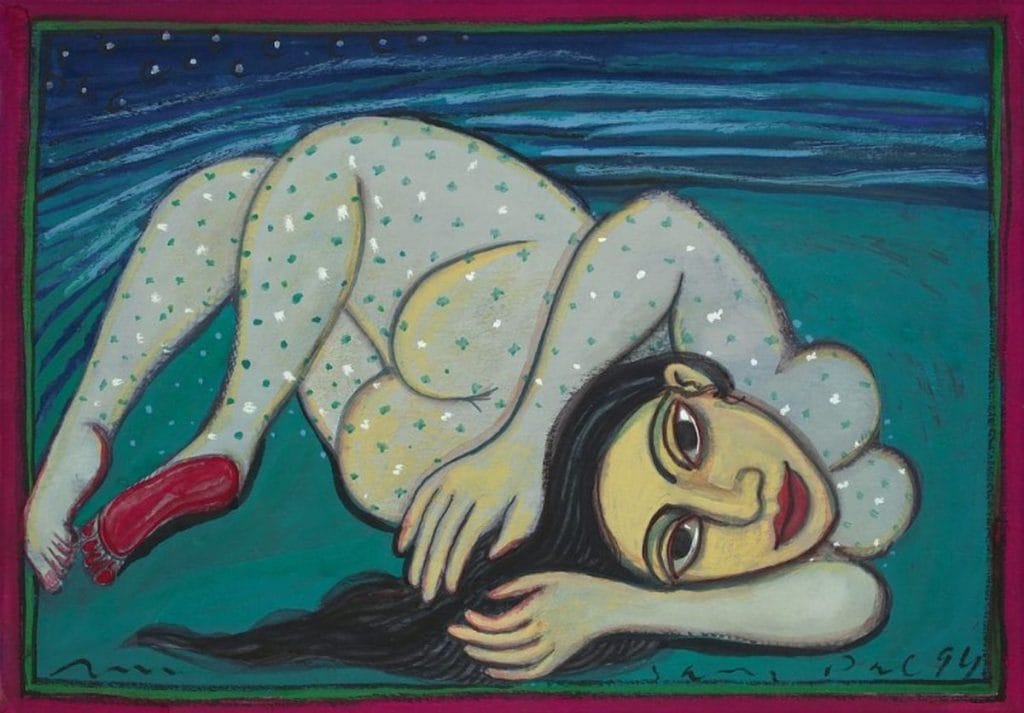

In her Kamdhenu paintings, she fused the female form with the mythical wish-fulfilling cow, using the hybrid body to ask what society demands of women. And in her Nayikas series, she reimagined the longing heroines of Pahari miniatures as women joyfully absorbed in themselves. She portrayed women not for the male gaze, but as celebrating their own desires.

Married to the artist and sculptor Ved Nayar, Pal’s feminism was never about creating a “breach” in the relationship between women and their role as nurturers, said curator Kishore Singh, author of Gogi Saroj Pal: The Feminine Unbound, based on a 2011 exhibition of her work at the Delhi Art Gallery.

“For her, women were always nature’s nurturers, so they were mothers, daughters, sisters, wives. And these roles she identified with,” he said. “However, she also insisted that women remain self-aware of their own needs and desires. She was always concerned with othering, the other, the marginalised, often within family situations, too.”

Also Read: Hanif Kureshi—the artist who converted Delhi’s Lodhi Colony into the first art district in India

‘My DNA is unusual’

Pal is often celebrated for her ‘defiance’. She herself had a fondness for the word ‘troublemaker’. Singh said she’d recount how when boys tried to tease or bully her, she would beat them up.

That fierceness came from the women in her family. Her mother refused to cover her head with a veil, and stood up to social judgement.

Pal also often cited her “Paharan” grandmother as an influence.

“My grandmother was the first woman who opened an orphanage for girls in Lahore,” she said in the Art Life interview. “My DNA is unusual, and I am happy with it”.

Born in 1945 in Neoli, Uttar Pradesh, Pal, whose father was a freedom fighter, studied at the College of Art in Vanasthali, Rajasthan, and later in Lucknow, before completing a postgraduate diploma in painting at the College of Art, New Delhi.

The capital became her lifelong home, though she never tried to fit into any circle. She set up her studio and dressed with flair, her neat hairstyles and colourful outfits often mirroring the women in her paintings.

Singh said she’d call friends over for fortnightly gossip sessions over multiple cups of black tea and cigarettes.

“She smoked like a chimney and fired off questions about everyone’s whereabouts, there was no way anyone could escape those sessions,” he recalled. “She was bold and absolutely spoke her mind, pulled no punches, but at the same time, she was very warm and affectionate.”

Much of the time, though, she stayed behind shut doors at her New Friends Colony house, spending long hours in the studio, always experimenting.

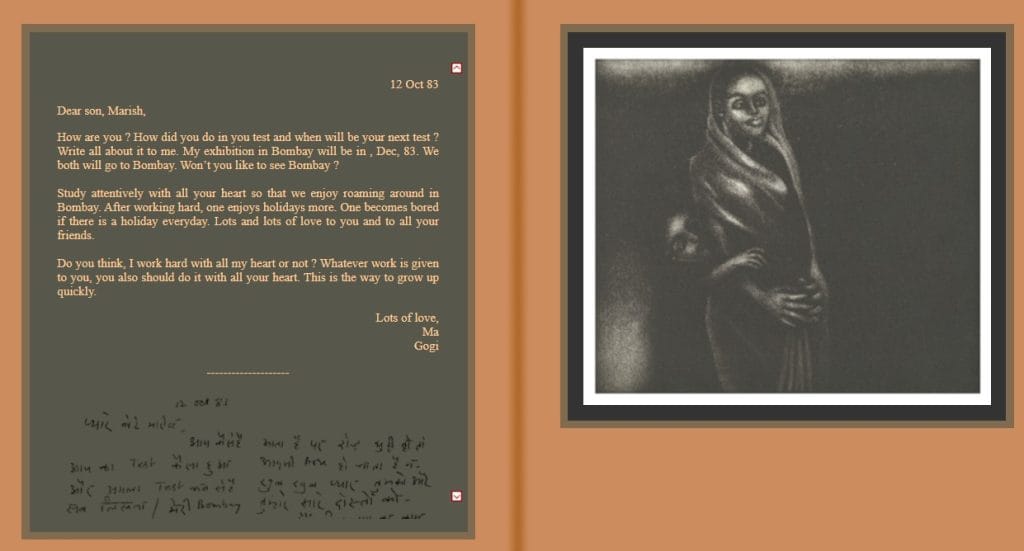

Work also became an escape from grief after she lost her teenage son Marish to an accident.

Her letters to him when he was in boarding school are still preserved on her website.

“I wrote to my son on any issue that came to my head — art, Dussehra, Independence Day, my exhibitions — anything,” she said in a 2004 Telegraph interview. “Painting keeps both the mind and hands busy. I blocked out everything else.”

Singh said she also channelled her nurturing instincts to the children of her attendant staff.

“She brought them up as her own,” he said.

Also Read: Kapila Vatsyayan was not afraid of anyone. Dance to art, she was a cultural architect

‘You dig a well every day’

In Mandi, a woman from a red-light district stares straight back, taking control of the gaze. So do the mothers in Halley’s Comet II and Mother and Child, unclothed and unashamed.

Pal worked with diverse mediums such as installation, painting, sculpture, graphic print, ceramics, jewellery, weaving, and photography. In 1965, she held her first show in Lucknow and sold her first paintings, three for Rs 30 each. Over time, though, she refused to build any mythology around success. The work itself mattered more than sales or applause.

“I felt that I was an artist [back in Lucknow]. There is no such thing. Nothing happens by selling. It happens by doing,” she said in the 2021 interview. “You dig a well every day, drink water every day, walk every day, get tired, then dig a well, then drink water, then get tired. This is how it is.”

The women in many of her paintings are just as self-contained. In her Nayikas series, Pal took an ironic look at the heroines of miniature traditions, especially Pahari painting. The traditional nayika waits, clothed and bejewelled, longing for her lover. Pal’s nayikas appear joyfully naked, adoring themselves.

Art, to her, was “like breathing” and always paramount even though she also taught at Jamia Millia Islamia and the College of Art.

“I don’t think that I will take a class first, then if there is time left, I will do art. Class bhaad mein jaye (class can go to hell),” she said. “I will eat less. I will live in a small place. But I have to do art.”

Pal’s fierceness and rebelliousness reflected in her paintings. Her early series Being a Woman and Relationship introduced the hybrid figures that became central to her imagination: Kamdhenu (half woman, half cow), Kinnari (half woman, half bird), and Dancing Horse (half woman, half horse).

“In all of her works, her subjects are enjoying and beautifying themselves, they are celebrating femininity, but they are doing it for themselves not for the patriarchal society,” said Singh.

In her final years, she began turning the figures of her Nayikas into large fibreglass sculptures. The work was left incomplete.

“We needed another decade of her art,” said Singh.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)