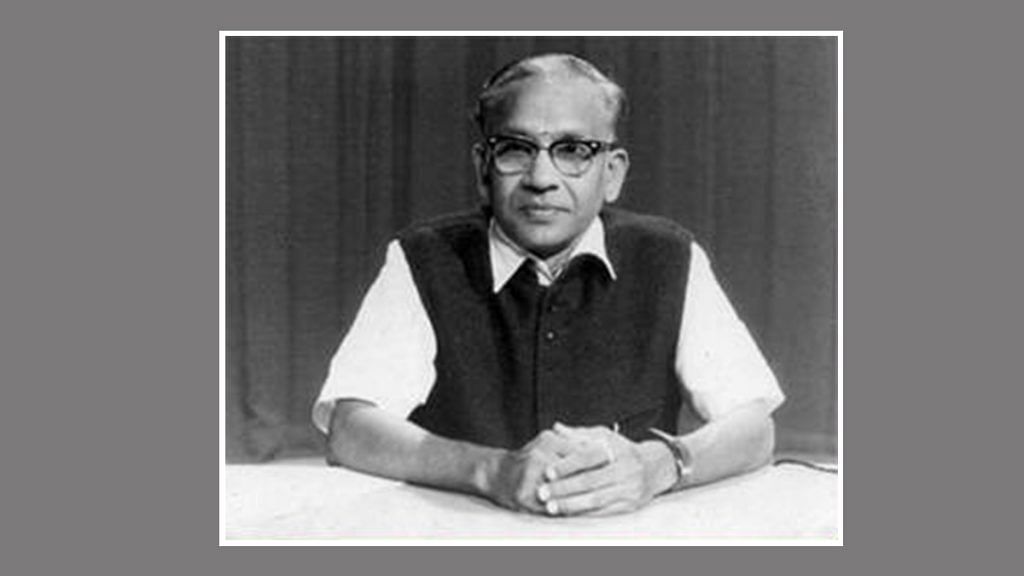

Journalist, travel writer, satirist, orator, freedom fighter — Akilan, the first of only two Tamil-language Jnanpith awardees, wrote and translated more than 20 novels, 200 short stories, essays and plays.

Before his first story, Avan Yezhai (He Is Poor), was published in his high school quarterly magazine in 1939, Akilan’s headmaster read the draft. It was so powerful and compelling that the man couldn’t believe it was the schoolboy’s own. But the story, about a young, poverty-stricken boy who wanted to kill himself, was not only original, it was also inspired by Akilan’s own life.

Also read: M.F. Husain, the bold & prolific artist who started his journey painting movie billboards

Early life

Born on 27 June 1922, in Perungalur in Pudukottai Tehsil, Akilan lost his father when he was in school. His father’s second wife, Amirthammal, sold appalam (a kind of poppadum) and keerai (spinach) to make ends meet, at least until Akilan finished studying.

As a young lad, Akilan was very much inspired by the writings of the Tamil scholar and essayist Thiru. Vi. Ka. (Thiru V. Kalyanasundaram), a staunch humanist and freedom fighter.

In school, he became an active freedom fighter, participating in the picketing of toddy shops and protests against foreign cloth. Although he eschewed college education in favour of a job, Akilan continued his extensive reading, from Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Nikolai Gogol to Mikhail Sholokhov, Voltaire and Guy de Maupassant.

The turning point

After a stint in the Tehsildar’s office and then as a sub-editor at a magazine, Akilan became a letter sorter with the Railway Mail Service (RMS) in Tiruchirappalli and then Tenkasi.

But soon, he moved to Chennai to work as a producer with All India Radio (AIR), which proved to be a turning point. A staunch Gandhian at the time, he would, among other things, read out parts of Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments With Truth, to listeners every week. This was also where he met popular Tamil writer Uma Chandran and soon, decided to become a full-time writer.

Akilan the writer

His first novel, Mangiya Nilavu (Murky Moon), was published in 1944 (edited and re-released in 1949 as Inba Nilavu). From then on, he wrote everything from historical novels to plays, travel writing, short stories and children’s books.

If the Sahitya Akademi award-winning Vengaiyin Maindhan (The Tiger’s Son) is a historical look at the Chola empire, in Ezhuthum Vazhkaiyum (Of Writing and Life), he spends a chapter discussing his personal experience of the time when Gandhi was assassinated, and how he came across “Godse-like” people distributing sweets in the streets of Tiruchirappalli to celebrate the news. Politics is a recurring theme in his works, as are the quotidian struggles of the everyday person and the life and struggles of a writer.

Legacy

Akilan died on 31 January 1988. But he left behind a body of work that has ensured his relevance to this day. His writings won multiple awards, including the Jnanpith in 1975 — the first Jnanpith to be awarded to a Tamil writer — and have been translated into a slew of languages, including Russian and Chinese.

Many of his works were adapted for the stage and silver screen, with iconic actors such as M.G. Ramachandran and Sivaji Ganesan essaying major roles. But his legacy isn’t confined to the page. He was uncompromising in his views, yet able to adapt, and outspoken to the end.

During his visits to USSR, for example, his exposure to Socialism, Marxism, and Leninism made him a critic of the same Gandhian principles he had espoused for so long. Later, he had even concluded that Gandhian philosophy had failed the nation. He was critical of many local leaders in Tamil Nadu and even called DMK a fascist party.

His son, Akilan Kannan, also a writer, tells ThePrint, “For me, he is an embodiment of love. His writings have always proved his affection for humanity. He never compromised on his stance. That was his huge strength.

“He was very emotional and such emotional writings took a toll on his health. During the Emergency, when someone had warned him about my involvement in a magazine with Communist leanings, he said, ‘the Gandhian principle did not work for us. I am sceptical about Communism too’. But he left it to me to choose my own path.”

Also read: Ismail Merchant, the filmmaker who gave the world a new lens to look at Indians