India wants to learn from Malaysia’s deradicalisation programme which is based on the belief that not only is it imperative to counter security threats posed by convicts but it is also incumbent on the state to rehabilitate them.

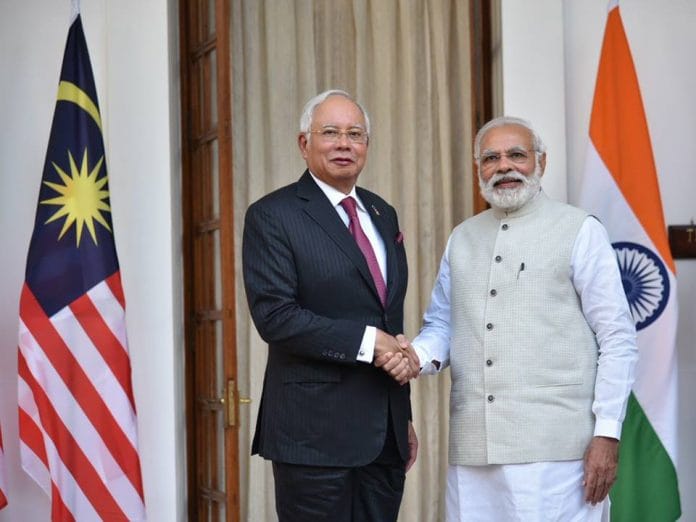

Expressing his concern over growing conventional and unconventional threats to security, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has sought to understand better Malaysia’s internationally recognised programme for deradicalistion for convicts involved in extremist, radical and Islamic State movements. During a bilateral meeting with his Malaysian counterpart Najib Razak, Modi expressed concern over the rising cases of radicalisation and youths getting drawn to ISIS. Razak, it is reported, presented Modi a book on his country’s deradicalisation policy.

According to the country’s Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, the programme, which is implemented under the Malaysian Prisons Department, has achieved a high rehabilitation rate of 97 per cent. Explaining the nuances of the programme in a speech at the 226th Prisons Day celebration at Padang Merdeka last year, he said that the success of the programme lay in incorporating different sections of society, including psychologists, NGOs, religious experts, and Jakim (Malaysia Islamic Affairs Department), to convince the radicalised against returning to violence.

At the heart of the deradicalisation programme is the belief that not only is it imperative to counter the security threats posed by convicts, but it is also incumbent on the state to rehabilitate them. Fundamentally a persuasive exercise, the programme is based on both theological and strategic lines. The former entails invoking the Quran to establish that Islam forbids aggressive warfare and insists, instead, that the lives of non-combatants, particularly women and children must be protected. The latter, on the other hand, seeks to challenge the existing rhetoric which paints all Westerners as enemies and anti-Muslim by stressing, for example, the fact that many Americans opposed the war in Iraq.

The Malaysian government has framed an extremely structured programme designed to rehabilitate those involved in terrorist activities, consisting of three stages: the early detainment period, the detainment period and the post-detainment period.

In the first period, the individual may be detained for a period of no more than 60 days for investigative purposes. The purpose of this stage is to persuade the individual to relinquish violence and religious bigotry that often spurs violence. The detainee is then released if the authorities are convinced that he has ceased to pose a security threat. If not, he is sent to the Kamunting Detention Centre for a period of two years, which may be further extended as per the discretion of the authorities.

Placed at the Kamunting Detention Centre, which is under the purview of the Prisons Department of Malaysia, the detainee begins the second stage of the de-radicalisation process. Also known as the Human Development Program, rehabilitation entails three basic elements, including discipline development, personality enhancement and social skills and training programme. The underlying purpose of all these activities is to help the individual bridge the distance between self and the society, which may have arisen as a result of years of radicalisation and disillusionment with the world. Moreover, at the Detention Centre, professionals from various quarters are asked to collaborate in the project to make the detainees disengage themselves from their past activities.

The third and final stage of the rehabilitation programme is the post-detainment period. A perpetually ongoing stage, the post-detainment period begins in the immediate aftermath of release. Even after release, the detainee is required to keep in ‘close contact’ with the police, which essentially include regular reporting to the police station nearest to his or her residence.

While India too continues to dabble with the idea of deradicalisation in many states including Maharashtra, UP and Telangana, to name a few, there is nevertheless rampant institutionalised abuse of terror suspects and convicts in the country, rights activists say. A concerted programme that reintegrates such individuals into society and removes the social stigma such as ostracisation and a lack of employment, is urgently needed as a genuine deradicalisation programme gives a much-needed humane touch to the largely belligerent war against terror.

Sanya Dhingra is a Reporter with ThePrint. You can follow her on Twitter @DhingraSanya

Picture courtesy: Narendra Modi’s Twitter handle