New Delhi: The Supreme Court Wednesday questioned the place of unilateral divorce in a modern democracy, signalling that the practice of Talaq-e-Hasan—a form of divorce in which a Muslim man can end his marriage by pronouncing the word ‘talaq’ once a month for three months—may be incompatible with a “civilised society”.

A bench led by Chief Justice of India-designate Surya Kant is scrutinising the practice where a marriage is dissolved following three pronouncements made over three months if the couple does not resume co-habitation.

“What kind of thing is this? How are you promoting this in 2025? Whatever best religious practice we follow, is this what you allow?” Justice Kant asked. “Is this how a dignity of a woman (is to) be upheld? Should a civilised society allow this kind of practice?”

While the Supreme Court struck down instant triple talaq (Talaq-e-Biddat) as unconstitutional in 2017, it left other forms of unilateral divorce, including Talaq-e-Hasan, untouched.

The court was hearing a petition by journalist Benazeer Heena, who argued that Talaq-e-Hasan was a violation of fundamental rights, specifically Articles 14, 15, 21, and 25 of the Constitution.

Heena approached the court after her husband allegedly sent her a Talaq-e-Hasan notice through a lawyer following a dispute over dowry.

Justice Kant remarked that when society at large is involved, remedial measures must be taken if “gross discriminatory practices” exist.

ThePrint explains the practice of divorce and how courts have reacted to it in recent years.

Also Read: SC judgement on triple talaq: What’s monumental about it and what’s not

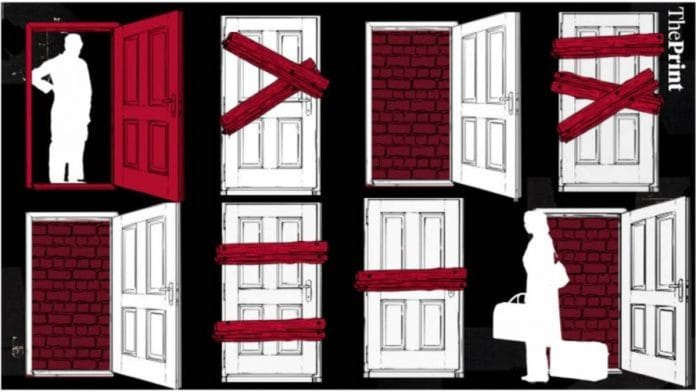

Kinds of divorce & court rulings

In 2017, the divorce practice banned by the Supreme Court in the Shayara Bano judgment was Talaq-e-Biddat or instant triple talaq in which a marriage could be ended instantaneously by pronouncement of “talaq” three times in a single sitting. It is now a criminal offence under the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019.

In contrast, the current challenge is against Talaq-e-Hasan, in which the husband pronounces “talaq” once a month for three consecutive months to end the marriage. This is separate from Talaq-e-Ahsan, considered the most approved form of divorce in Islamic jurisprudence.

Talaq-e-Ahsan involves a single pronouncement of “talaq” followed by a waiting period, or iddat, of three months. If the couple reconciles and resumes cohabitation before the three months are over, the divorce is considered nullified. However, it becomes final if reconciliation does not occur during this waiting period.

A woman, on the other hand, can initiate divorce through Khula, which can be sought with mutual consent or through court proceedings if the husband does not agree. Here, the woman can end the marriage by returning the mahr (gift at the time of marriage) to the husband or agreeing to other financial settlement. Islam also allows for Mubarat, a form of divorce where both spouses mutually and voluntarily agree to end their marriage.

The 2019 Act did not criminalise Talaq-e-Hasan and it thus remains legal.

The Supreme Court previously did not voice such strong disapproval against the practice. As recently as 2022, a bench comprising Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul and M.M. Sundresh had orally taken an opposite view, suggesting the practice was not prima facie improper because it allowed time for reconciliation.

“Prima facie, this (Talaq-e-Hasan) is not so improper. Women also have an option. Khula is there. Prima facie, I don’t agree with petitioners,” Justice Kaul had said in 2022, warning against using the court as a tool for other agendas.

Both the Himachal Pradesh and Kerala High Courts have also previously refused to interfere, noting that Parliament’s 2019 law targeted only instantaneous triple talaq.

The Himachal Pradesh High Court had observed that the Shayara Bano decision and the 2019 Act criminalised only Talaq-e-Biddat, and that other traditional forms of divorce, including Talaq-e-Hasan, were not affected by the change.

It had also said that other forms of divorce, that came into effect after a certain period, were approved by the Prophet Mohammad and valid according to all schools of Islamic law. The court, with this view, quashed a complaint against a husband accused of issuing a written divorce notice over three months.

The Kerala High Court made similar observations in 2022. It clarified that Talaq-e-Ahsan and Talaq-e-Hasan remain valid, and that the Shayara Bano verdict did not invalidate them.

“Both these forms are still legal and valid under Muslim personal law,” it observed.

The court also explained the rationale behind Talaq-e-Hasan, noting that the practice was historically intended to prevent abuse and introduced to put an end to barbarous pre-Islamic practices where men would divorce and take back wives repeatedly to torment them.

“The Hasan form is one in which the Prophet tried to put an end to a barbarous pre-Islamic practice. The practice was to divorce a wife and take her back several times in order to ill-treat her,” the HC noted.

A similar challenge had earlier reached the Delhi High Court through petitioner Raziya Naaz, who alleged that a divorce notice under the practice was used to pressure her into withdrawing a domestic violence complaint.

Naaz had contended that the practice was “abominable” and argued that such “unilateral extra-judicial divorce” should not be permitted.

According to court records accessed by ThePrint, she withdrew the petition in 2023 to pursue intervention before the Supreme Court in Benazeer Heena’s case.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: As India debates triple talaq, here are 9 Islamic countries that have regulated divorce