Vasco Da Gama: Every December, as Indians flock to Goa for some coastal respite, glaciologist Vikram Goel and his colleagues do the opposite. They leave the coastal state for a ‘summer’ destination – Antarctica. The Indian winter coincides with the polar summer, when it becomes suitable enough to brave the icy continent and work in the ‘pleasant’ 0 to minus 10 degrees Celsius weather.

It’s the busiest time of the year, not just for Santa Claus, but also for the National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). Their climate and environmental scientists, biologists, geologists, oceanographers, and glaciologists, like Goel, have been travelling to Antarctica to study its frigid atmosphere for a quarter of a century now.

As one of the fastest-warming places in the world, studying Antarctica is key to studying climate change, and Indian scientists are on top of it.

From joining the Antarctic Treaty in 1983 to now having two permanent research bases on the continent, with a third one on the way, India has steadily expanded its exploration of Antarctica. Scientists have mapped more than 20,000 sq km of the land, found geological similarities between East Antarctica and the Eastern Ghats in India dating back to 500 million years ago, and drilled ice from 400 years ago in unknown parts of the continent.

At the centre of it all is the NCPOR, India’s nodal agency for both polar and oceanic research.

“We are an organisation that deals with extremes – we research in the extreme conditions of Antarctica, the Arctic, even the Himalayas. What is going on in Antarctica, in its ice, its history, the bacterial and animal life in those extreme conditions? It is our job to find out,” said Thamban Meloth, Director of NCPOR. “On the other hand, we also work in deep ocean research, which is another extreme environment.”

From global volcanic events to past El Niño circulations to the presence of microbial life, scientists at NCPOR have been able to decode global events through Antarctic ice.

NCPOR runs two world-class research stations – Bharati and Maitri – in Antarctica, making India one of the 30 countries in the world to have a permanent research presence on the continent. As the nodal government institution for the poles, NCPOR also ferries young Indian scientists to the polar continent to study Antarctic climate, ice thickness, its rate of melting, secrets inside the snow and life in extremes. But that’s not all they do – they bring Antarctica to India too.

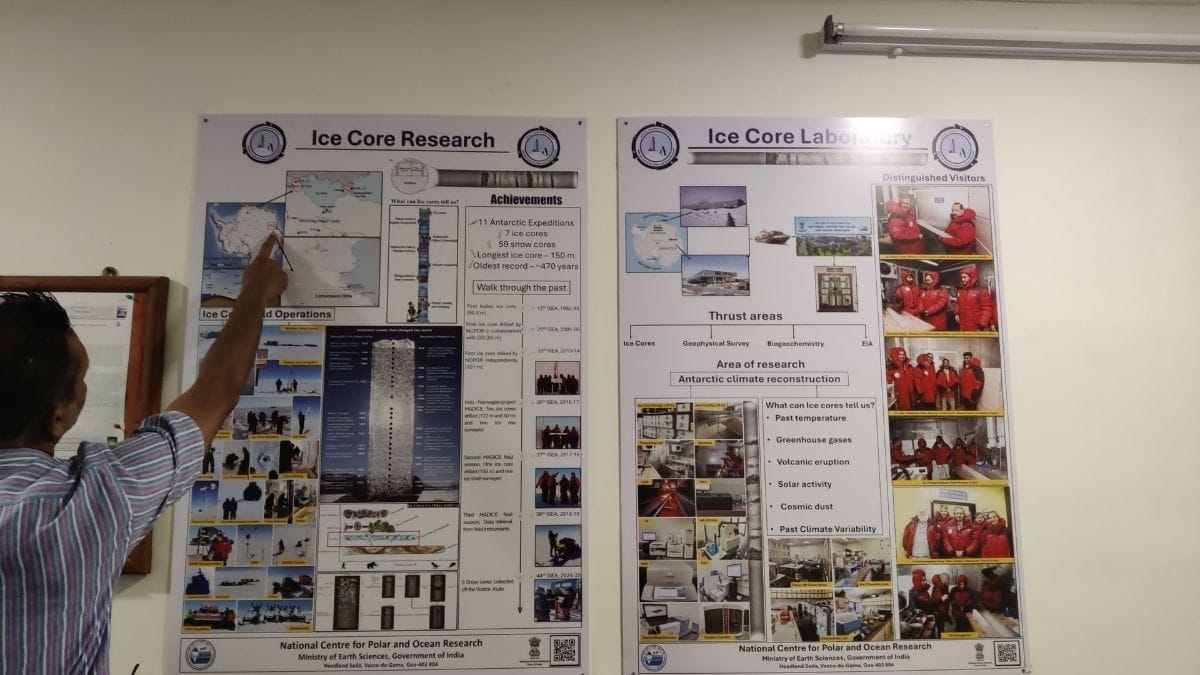

For years, NCPOR scientists have been drilling deep ice cores from the continent, containing layers of ice packed together. Each layer represents a year’s worth of snowfall, and the scientists bring it back to their headquarters in Goa to study. Their latest and largest core is 150 metres long and contains more than 400 years of snowfall. Now, NCPOR scientists are analysing the core and uncovering the history of Antarctica, one layer at a time.

“The thing with Antarctica is that it is the biggest source of uncertainty in all our global warming, climate change, sea-level rise estimates,” said Goel. “The only way to get rid of this uncertainty is to study its history. When we know its history, is when we’ll be able to tell its future.”

Also read: Uttarakhand forests are turning deadly for women. They’re victims of rising animal attacks

The Antarctic ice-core project

Inside the lush green NCPOR campus in central Goa is a room where the temperature dips to Antarctica levels, at -20 degrees Celsius. Known as the Ice Core Laboratory, it stores ice samples collected from Antarctica and the Arctic in large custom-made ice boxes. These boxes are the closest scientists can get to an archive of Antarctica.

This is also the primary laboratory of Prashant Redkar, an engineer who works at the Antarctic Cryospheric Studies Division.

“We drill the Antarctic surface using electro-mechanical and other machines, and retrieve a long, cylindrical block of ice to take back and study,” explained Redkar. “Ice is the best archive, because it doesn’t just freeze water but also air bubbles containing gases, trace particles of dust and metals, and isotopes of oxygen of previous years,” he added.

Clad in a bright red, puffy suit – much like the ones he wears on his trips to Antarctica – Redkar walks through a metal door into the freezing laboratory. The lab is equipped with saws and machines to process the ice without contaminating it. Since the Ice Core Laboratory was first established in 2005, there have been 11 different expeditions to Antarctica to bring back ice cores from different parts of the continent to study.

Antarctic ice is, simply put, the only record of the Earth’s past climate and atmosphere available to scientists. Ice freezes air bubbles and microbes for centuries and even millenia, so when it is extracted and melted, all the frozen material can be studied as it was in that time period.

Both of India’s stations are located in East Antarctica in the 1.5 million sq km expanse known as Dronning Maud Land, and this is where NCPOR’s ice cores are usually drilled from. Being near the Antarctic coast, the ice cores collected by NCPOR give special insights not just into Antarctica but also the Southern Ocean surrounding it.

When it is time to study, the cores are sliced into layers of 5cm, with each circular layer representing anywhere between a few months to several years in Antarctic history. Once it is processed in the lab, the layer is cut in half through the centre – one half is stored as ice, maintained as part of NCPOR’s archival ice records. The other half is melted into water and studied for its properties.

In 2006, a study by NCPOR scientists, including Dr Meloth, found that ice from the last nearly 500 years had volcanic tephra and sulphur particles in certain years, which corresponded with major volcanic eruptions that took place in the world. In another study in 2009, biologists from NCPOR were able to find living microbes in the ice layers buried deep inside, from hundreds of years ago. This showed how ice from centuries ago was not ‘dead’, but rather hosted living particles from that time period.

Ice core records, therefore, bring together atmospheric scientists, chemists, microbiologists, and even glaciologists. Together, they play history sleuths while unravelling how natural and man-made events have impacted the climate in Antarctica and the rest of the world.

The -20 degrees Celsius ice core facility is surrounded by other laboratories, such as a Class 100 clean room facility, which is circulated with clean air every few hours for chemical studies of the ice. There is also a room where mass spectrometry studies are done on the oxygen and other gas particles found in Antarctic ice, to understand temperature differences in history.

Also read: India’s first dengue vaccine has been in the making for 17 yrs. DengiAll has the world excited

Why NCPOR in Antarctica and the Arctic?

Antarctica has, for years, been the place providing clues for global climate change – the hole in the Ozone layer was first discovered over Antarctica, the continent stores over 70 per cent of the Earth’s freshwater locked up in its ice, and ice core drilling from 400,000 years ago has shown how global temperature and carbon dioxide levels have always been correlated.

But beyond this, Antarctica also has a strategic significance, and that is why NCPOR is in many ways a strategic organisation too. While officially placed under the Ministry of Earth Sciences, NCPOR isn’t like any other normal research institution.

“We carry out the Indian government’s priorities in the Arctic and Antarctic, and they extend beyond science,” said Meloth. “It has geopolitical significance.”

Meloth, who has been to Antarctica five times and holds the record of being the only NCPOR scientist to have been to Antarctica, the Southern Ocean, the Himalayas, and the Arctic (both Svalbard and Greenland), explained the strategic reasons for India’s presence in the polar areas.

Referring to US President Donald Trump’s recent stake over Greenland, Meloth said it was the best example of the growing importance of polar regions as global warming increases.

“The melting of the sea ice in the Arctic is opening up new strategic shipping routes, new resources like hydrocarbons and new mineral deposits in Greenland— now everyone wants a hold on it,” said Meloth. “Both Antarctica and the Arctic are rich in resources, fisheries, and they’re important transport routes – they’re the only regions available for the future. Of course, the Antarctic Treaty and the Madrid Protocol do not permit any mineral resourcing, but who knows what will happen in future? ”

Also read: Maharashtra’s Kham shows even ‘dead’ urban rivers can be revived—here’s the blueprint

History of NCPOR

India’s expeditions to Antarctica began in 1981, but it wasn’t until 2000 that a dedicated institution was established for polar and ocean research. With over 100 scientists, researchers and professors working in different fields of polar and ocean research, the organisation boasts of a ‘multidisciplinary’ faculty. It also offers opportunities for PhD scholars from Goa University and the University of Mangalore to conduct their research through NCPOR’s help, under their scientists.

As for the research itself, NCPOR follows the same themes that most of the other countries with bases in Antarctica do: geology, climate studies, ice core drilling and ocean-land interactions. The difference lies in the area of study.

“You have to understand that Antarctica is a huge continent, and one that has never been explored,” said Meloth. “So the kind of ice cores or glacial thickness we find in East Antarctica will be vastly different from central Antarctica, and so the studies and research will be different too.”

Even though both of India’s stations – Himadri and Maitri – are located 2,500 km away from each other, which is as far as Kashmir to Kanyakumari. At each station, some scientists work in remote sensing, others focus on marine studies, and still others study the microbial life deep within the Antarctic surface. Many NCPOR scientists also collaborate with other countries’ researchers from time to time, chipping away at the history of the continent one ice core at a time.

While Antarctica was the first destination for scientists, India now has a significant research presence in the Arctic too, with a research station, Himadri, in Svalbard. Most recently, NCPOR also established a station, Himansh, in the remote mountains of Spiti Valley to monitor the Himalayas.

As a glaciologist, Goel’s work is in the Antarctic Cryosphere and Environment section, and his research field extends across almost the entire continent, basically any place that has ice. He has been there five times already, including as part of a one-of-a-kind international mission to West Antarctica.

Going to Antarctica

Choppy helicopter rides, blizzards, and endless sunny and snowy days. In five visits to Antarctica in seven years, Goel has braved the extremes to gather knowledge that may resolve some of the world’s pressing questions. He has spent nights sleeping in a hovercraft, watched tents collapsing during sudden summer storms, and charted out courses in parts of Antarctica no human has ever visited before.

In his office, along with detailed maps of the Antarctic coast and the ice sheets, he also collects badges from each expedition he has completed — SENS exploring the Nivl ice shelf with Norwegian scientists, RINGS mapping the bed topography of the Antarctic ice sheet, and RAICA, exploring the Ross-Amundsen ice shelf in West Antarctica, with Korean and American scientists.

While ice is his mainstay, Goel’s work revolves around using geophysical tools like ice-penetrating radar, and seismic surveys and gravimetry to study the ice from the surface. He describes it as performing ‘ultrasounds’ over the ice sheet or glacier, to understand what lies underneath without needing to dig.

“Ice radar and ice core drilling go hand in hand – while radar measurements will give you a spatial, broad overview of the region and the thickness of ice and how many layers are there, drilling an ice core will give you the age of these features and provide a comprehensive history of the ice,” he explained.

His participation in the RAICA Expedition, which was the first time ice cores were being drilled in the remote West Antarctic region of the Canisteo Peninsula, was an example of how radar and drilling worked together. He was representing India in an expedition with Korea, USA, Norway and the UK to build an array of ice core samples from West Antarctica, the region that is melting the fastest yet has been explored the least.

Radar is also a great way for scientists to figure out where exactly to drill the ice. It gives a snapshot of the layers underneath, pointing towards areas with more ice, firmer layers, and ideally – a Raymond arch. This is an ice mound that stands out as a U-shaped arch within the ice, and is usually the best spot to drill ice cores in.

“The layers in a Raymond arch are pushed upwards, and are more compact than in the areas nearby. So if I drill 100 m in a Raymond arch, I might get 200 years of snowfall layers, but in another area just a few metres away, it might be less – maybe 100 years,” explained Goel.

This is the exact process he used for NCPOR’s next project, which is an ambitious effort to get ice core data.

Also read: The Guardian of the Aravallis and his 30-year fight

What is next?

Scientists at NCPOR also have in them a little bit of a historian. They live by Confucius’ famous adage, that one should study the past to define the future. For their next project, NCPOR wants to get an ice core that delves into the last 20,000 years.

20,000 years ago is a geologically young yet significant time – it was the period of the Last Glacial Maximum, or the last Ice Age that the earth underwent. Getting data from that far back can help NCPOR understand a lot about how snowfall, temperature and biology have changed since that time, and especially compare it with current climate change levels.

There were a lot of factors the NCPOR scientists had to consider. To drill such a large piece of ice, they needed to make sure the region was stable enough for their powerful machines. They also wanted to ensure accessibility to their research stations, and most importantly, they wanted the maximum amount of information possible from a single drilling operation.

It was up to Goel to scout for the ideal location. He spent days on his snowmobile apparatus, cutting a lonely path across the Kamelryggen ice shelf (KAM), sending radar signals into the ice to assess its thickness and layers. Days of hits and misses later, he stumbled across a striking site – One ice mound, or Raymond Arch, in the Kamelryggen ice rise (KAM) had layers of ice up to 20,000 years available 450 m from the surface.

This meant that the NCPOR scientists would need to undertake their largest-ever drilling mission and get the longest ice archive in the organisation’s history. The site was also close to the Maitri research station in Schirmacher Oasis, making it ideal for when actual drilling work begins.

Meanwhile, another line of inquiry takes NCPOR researchers back to their scientist-historian role –looking for a geological connection between India and Antarctica.

“India and Antarctica share a deep geological past, and we’re trying to study their joint history from the Precambrian era, before India made its northward journey towards the Eurasian plate,” said Meloth.

A billion years ago, when the Earth’s landmass was all part of a large supercontinent of Gondwana, the NCPOR scientists hypothesise that East Antarctica and the Eastern Ghats of India were actually neighbours. They are studying the rock varieties and formation types in both regions, looking for signs of similarity.

They might get lucky soon enough, too. They found that the geological bridge between India’s Eastern Ghats and Antarctica is the Larsemann Hills region in East Antarctica.

It is in this fragment of shared history that NCPOR decided to build its Bharati research station in 2012, roughly 130 million years after the continents had parted ways—in a quiet nod to the millennia that India and Antarctica had remained side-by-side.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)