Amroha/Sonipat/Moradabad: When Somveer’s wife first fell ill, they rushed from Amroha to Meerut. The doctor brushed it off as “just low platelets”. They spent money they didn’t have, waited, hoped, and eventually she seemed to recover. But last year, her health crumbled. Her body grew frail, bones jutting out, and dizziness became constant. A local physician ran a few tests and gave the verdict: leukaemia.

Somveer, 32, a tailor, couldn’t imagine affording cancer treatment. They set their sights on AIIMS Delhi, nearly 250 kilometres from their village in Amroha, Uttar Pradesh. Until despair led them to a name whispered in passing: OncoCare Cancer Hospital, located within the same district, less than an hour’s drive from their home. It was affordable, accessible, and within half a day, they had a bed. For the first time in weeks, Somveer and his wife could breathe.

“We don’t know if the treatment is cheap or expensive—we’ve never been to big city hospitals. We couldn’t afford to. We’ve already spent Rs 14-15 lakh since she fell ill two years ago. I’ve been borrowing money, just hoping she gets better. Thankfully, she is doing better now, and it helps that there’s a hospital near our village,” said Somveer.

Like Somveer, many Indians are now accessing cancer care not in distant metros, but in newly equipped hospitals closer to home.

Cancer erodes financial stability and mental resilience, creeping in silently but wreaking swift and often devastating impact. Over 2.5 million people in India are living with the disease. Each year brings 7 lakh new cases and more than 5.5 lakh deaths. But India is now fighting back, strategically and at scale. What’s changing is where the battle is being fought.

For decades, cancer care was synonymous with big-name hospitals in metro cities—AIIMS-Delhi, Tata Memorial, Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute & Research Centre. But the ground is shifting. Whether it’s Amroha in UP or Panipat in Haryana, quality treatment is no longer a distant dream. Small towns are becoming new epicentres of cancer care.

This shift is oxygenated by both public institutions and private pioneers, fuelled by a rising number of patients.

The government is executing reforms designed to bridge the long-standing urban-rural divide in care. Under the National Health Mission, plans are afoot to set up 200 new district-level day-care cancer centres in 2025 alone. The goal is to ensure that no Indian, regardless of pin code, is left without at least basic cancer care.

There was a time when stage 3 was dominant. Stage 4 was very common. Stage 2 was less, and stage 1 negligible. Now the trend is moving backwards

-Arun Kumar Goel, Andromeda Cancer Hospital, Sonipat

AIIMS branches in Bhopal and Jodhpur are developing a decentralised model that turns tier-2 cities into tertiary cancer care hubs linked to district and primary centres. Tata Memorial Centre is expanding beyond Mumbai, building new facilities in Kharghar and launching paediatric cancer units in places such as Varanasi, Guwahati, and Visakhapatnam through public-private partnerships.

But this isn’t just a top-down movement. There’s also a reverse migration of doctors, who are setting up cancer hospitals in their hometowns: Panipat, Sonipat, Meerut, Amroha. Highways and roads in tier-2 cities are plastered with towering hoardings featuring the faces of local oncologists, their degrees and patient counts written like medals, selling hope in bold, oversized fonts. Many have been trained at Fortis, AIIMS, Max, and other major hospitals.

They are driven by convictions in better access to cancer treatment— and also a greenfield opportunity. A market where need is massive, competition is limited, and the rewards are both human and financial.

“People are coming from all over the country to centralised hospitals like Tata Memorial, AIIMS, and BHU, which are now overtaxed. So we need small centres in tier-2 and tier-3 cities. That’s why the government is opening clinics for chemotherapy outside major metros like Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata,” said Pramod Kumar Julka, vice chairman, Medical Oncology, Max Institute of Cancer Care. “In Punjab, there’s a ‘Cancer Train’ that takes patients for radiotherapy and brings them back the same day. This shows how cancer centres are being established closer to patients, so they don’t have to travel far.”

Also Read: Haryana to Manipur—private hospitals struggle with Ayushman Bharat. Govt owes Rs 1.2 lakh cr

Cancer care in the hinterlands

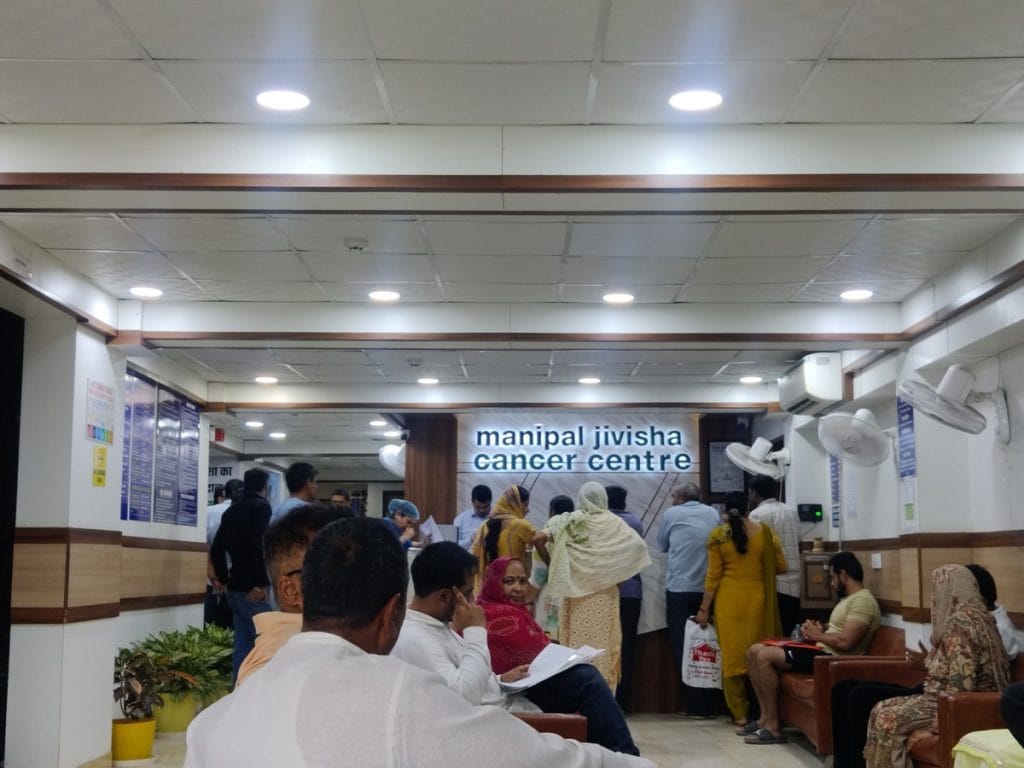

At the waiting area of Manipal Jivisha Cancer Centre in Sonipat, the silence is anything but calm. Patients clutch thick files, whisper into phones, or stare blankly ahead. Some chew their nails, others lean on loved ones for comfort. A woman rubs her temples, a child sleeps in her lap. They all looked worn out — fatigue hangs in the air, but so does hope.

This is one of the leading cancer facilities in Sonipat, and it didn’t exist until three years ago.

The hospital was founded by Dr Surender Dabas, 45, one of the country’s pioneers in robotic cancer surgery. Originally from Ladpur village in Haryana, he trained at Maulana Azad Medical College and later in the US. He became chairman of oncology at Fortis Hospital at the age of 36, and in 2016, India’s first trainer in robotic surgery, with over 150 doctors trained. But his roots called out to him.

“I wanted to come back to my hometown and give back,” Dabas said. “I saw the growing number of cancer patients in Haryana and felt the need for a hospital here. The vision is simple: to treat those who can’t afford expensive cancer care.”

At Jivisha, Dabas leads a 150-member team that travels across states conducting free OPDs. The hospital mainly treats lung, throat, breast, and bladder cancers. It doesn’t have a PET scan machine—patients are referred to Delhi—but offers chemotherapy, surgeries, and specialist consultations with a base fee of Rs 1,000.

“This hospital isn’t about making money,” he said. “That’s why I don’t aggressively promote it. More advertising brings more patients, and that can risk compromising the quality of care. That’s something I won’t allow.”

In the rural belt around Sonipat, dedicated cancer clinics and diagnostic labs are virtually absent. Government hospitals provide little beyond a Rs 3,000 monthly pension and free bus passes.

To bridge that gap, Dabas’s team conducts free OPDs in smaller towns across Uttar Pradesh and Haryana. They also offer free cancer screenings, with more than 25,000 people availing of this service over the past decade.

Just a few minutes from Delhi, the Andromeda Cancer Hospital in Sonipat stands out as the region’s only comprehensive cancer centre. Opened just a year ago, the 105-bed, doctor-led hospital offers chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, and houses Sonipat’s only PET scan machine.

There are too many quacks and too few real hospitals, so most people never even reach proper care. My mission is simple: anyone who walks through our door must get the best possible care. We see 4,000-5,000 new patients every year

-Dr Satyaveer Chauhan, founder of OncoCare Cancer Hospital, Amroha

Yet it is still not empanelled under Ayushman Bharat—an example, its directors say, of how small hospitals are left to fend for themselves in India’s cancer-care ecosystem. On a weekday, the building appeared deserted. Staff idled in consultation rooms or lounged in the canteen. Despite their medical expertise, the founders are caught in bureaucratic limbo, disheartened and frustrated.

“Some cancer treatment centres are coming up, but overall if you look at comprehensive facilities in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, there are much less compared to tier-1 cities,” said Nitin Zamre, director of Andromeda.

Decentralisation of cancer care has begun, but it’s far from equitable and progress is slow. Many specialists don’t want to shift to smaller cities, and infrastructure in peripheral centres is often compromised. Patients know this and so trust in the system is low. And so, those who can, still end up travelling to city hospitals.

“Setups that open up in the periphery sometimes do not put the infrastructure at a high level. They think that if the patient pays less, then we can put in a little lower quality infrastructure. So, then it tends to sort of feed into each other. The patient thinks that the infrastructure is less in the peripheral centres,” said Zamre.

Despite these systemic hurdles, increased awareness, education, and internet access have led to a crucial change: earlier diagnosis.

“There was a time when stage 3 was dominant. Stage 4 was very common. Stage 2 was less, and stage 1 negligible. Now the trend is moving backwards,” said Arun Kumar Goel, chairman of Surgical Oncology at Andromeda, who worked for years at Max Healthcare in Delhi before co-founding the Sonipat hospital. “Now, the proportion of stage 2 has increased, stage 3 is still significant, and the number of stage 4 upfront has reduced. And some patients have started coming in stage 1.”

The diagnostic divide, however, remains. India has no national cancer screening programme, unlike many countries in the West, and so detection is still often too late, according to Goel.

Trapped in red tape

In India, building a private cancer hospital outside a metro isn’t just a financial risk but a bureaucratic marathon. Despite growing demand for cancer care in smaller towns, those who try to bridge the gap face policy blind spots, heavy import duties for advanced equipment, and endless delays over NOCs and regulatory clearances.

“The most expensive piece of equipment in our hospital, a linear accelerator, the radiotherapy machine, costs Rs 21 crore. The problem is, it has to be imported because the machines made in India simply don’t meet the required standards. Imposing a 37 per cent import duty on something so essential is, frankly, criminal,” said Zamre.

The government has expanded customs duty relief on many cancer medicines, but numerous immunotherapy drugs and radiotherapy machines still face high taxes.

Even after a hospital becomes operational, securing Ayushman Bharat empanelments and clearances is painfully slow—the website crawls, verification takes weeks, and the process turns into a bureaucratic ordeal, despite being fully under government control

-Nitin Zamre, director of Andromeda Cancer Hospital, Sonipat

Costs are just one challenge. Systemic inefficiencies weigh new hospital projects down and precious time is lost. Zamre argued that the government needs to take a more practical, patient-centred approach to healthcare infrastructure. From construction permits to regulatory clearances, there is virtually no support at any stage, according to him.

“Even after a hospital becomes operational, securing Ayushman Bharat empanelments and clearances is painfully slow—the website crawls, verification takes weeks, and the process turns into a bureaucratic ordeal, despite being fully under government control,” he said.

Zamre added that doctor transfers are equally cumbersome, often taking months as they require multiple clearances from health departments, caught up in administrative cycles, backlogs, and political considerations.

“This lack of institutional support delays care and hits patients the hardest,” he said.

Meanwhile, India’s cancer-care sector is undergoing rapid corporatisation, pushing costs higher and narrowing access.

“You look at the majority of super-speciality hospitals in India—Max, Fortis, HCG, Manipal—all of them are getting corporatised,” said Goel.

This commercialisation drives up costs even in non-corporate setups. He compared his hospital to the Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute and Research Centre (RGCIRC), which is a trust hospital but still charges higher. “It is at least 35-40 per cent more expensive than ours, simply because it has become too big,” he said.

Caught in the middle are smaller, doctor-run hospitals trying to offer quality care without corporate backing. Most tier-2 hospitals are founded by oncologists who either take bank loans or bring in private investors, as Andromeda did. Without system-level support, they are left fighting both bureaucracy and market forces.

Despite being a 105-bed hospital, Andromeda’s outpatient numbers remain low.

“Ten to 15 OPDs per day is nothing,” Goel said ruefully. “The government has to really seriously think about it. It’s a very serious issue.”

Allopathy, Ayurveda, Ayushman Bharat

Vipul Goyal, 48, runs a jewellery shop in Moradabad. He has no shortage of money. But even that hasn’t made navigating cancer care any easier.

His younger brother has been battling colon cancer for three years. Weighing barely 40 kilos, he struggles to walk. “Whether he’s sitting on the bed or lying down, you can barely see him,” Goyal said.

The family has been through every major hospital from UP to Delhi, eventually landing at AIIMS, where his brother is now on immunotherapy. Each injection costs Rs 41,500 and must be sourced through a distributor in Delhi, as it’s not available at local pharmacies.

“I had colon cancer myself 10 years ago,” Goyal recalled. For him, the first signs were mysterious weight loss and pain. A colonoscopy finally revealed a small tumour.

“We went straight to Medanta (in Delhi). I lost 20 kilos and couldn’t move. But we caught it in time.”

This time, for good measure, they plan to supplement allopathy with Ayurveda.

“Chemo just poisons the body. Immunotherapy might help. Allopathy works in the beginning, but for the long run, Ayurveda is better,” he said. They’ve already been to an Ayurvedic doctor in Uttarakhand who has prescribed some herbs.

Many other patients too repose their faith in alternative treatments.

In Moradabad, Dr Mayank Sharma runs an Ayurvedic clinic, Ayurved Amritam, from his home. He sees 8-10 cancer patients at any time.

“Ayurveda is no longer slow,” he insisted. “We are advancing with research and studies every day. Ayurveda can stand on its own in cancer care, but for faster results, or to get the best of both worlds, we advise patients: get the surgery done first, then come to us. We’ll take care of the rest.”

Sharma, who has been practising for over 25 years, dreams of expanding his clinic to other cities and, as he put it, “taking the magic of Ayurveda to the world.”

Across UP, roadside posters promise Ayurvedic salvation: “Cancer cured naturally. No chemo. No radiation. 100% safe. 100% sure.” Even the roads seem to mirror the dilemma—billboards for oncology hospitals on one side, and, on the other, printed posters assuring ‘natural’ ways to get permanent freedom from cancer.

Patients face confusing choices. Cutting-edge Delhi or local hospitals, chemo or “miracle cures” promised in bold red and black fonts.

Within Moradabad, though, comprehensive cancer treatment facilities are hard to come by. Some hospitals offer surgery, others chemotherapy, but rarely everything under one roof.

At Cygnus Hospital, Dr Aabid Maqbool Lone handles it all. Originally from Kashmir, he chose Moradabad over Delhi despite better offers. “Both are far from home anyway,” he shrugged, one hand holding a telephone and the other scrolling through the medical histories of patients.

Since he joined in May, he has noticed an uptick in outpatient numbers: “Earlier, there were only 4-5 OPDs a day. Now, around 200 patients come in a month.” According to him, around 80 per cent are treated under Ayushman Bharat, at nearly half the cost of Delhi.

Also Read: Indian scientists, entrepreneurs are trying to understand chronic pain. Finally

Cancer care coming home

When Dr Satyaveer Chauhan left his private practice in Moradabad to open a bigger cancer hospital in his hometown of Amroha, it was a step toward bringing care to those who needed it most but could reach it least.

He had seen the problem firsthand: patients travelling hundreds of kilometres, spending money they didn’t have, just to get a diagnosis. In 2024, he opened OncoCare Cancer Hospital.

“There are too many quacks and too few real hospitals, so most people never even reach proper care. My mission is simple: anyone who walks through our door must get the best possible care. We see 4,000-5,000 new patients every year,” he said.

Chauhan hasn’t stopped at the hospital walls. He and his team go village to village, holding free screening camps in panchayat halls and under trees, telling people what they rarely hear about cancer: it is treatable if caught early. He is now building a women-only cancer centre, staffed entirely by female doctors and nurses, so women feel safe seeking care for cervical and breast cancers—the two most common, and the two most ignored kinds.

Chauhan’s efforts mirror a broader shift across India, as the government tries to close the urban-rural gap.

“All district hospitals to have daycare cancer centres,” Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced in this year’s Budget. Under the National Health Mission, 200 of these district-level day-care centres are due by 2025-26, bringing chemotherapy and diagnostics closer to home. Mass screening for oral, breast, and cervical cancers is being scaled up through the NPCDCS, a programme to prevent non-communicable diseases.

The 2025 Union Budget also cut customs duties on 36 cancer drugs, slashed GST from 12 per cent to 5 per cent, capped trade margins, and expanded low-cost generics through Jan Aushadhi and AMRIT pharmacies. The talent gap is being addressed too, with 10,000 additional medical seats announced and a target of 75,000 over the next five years.

Cancer is a silent epidemic in India’s villages, according to Chauhan. When he runs his medical camps in villages, people come in thinking they have a cough or a lump and many of them turn out to have cancer.

“One in ten people in some villages of Amroha has cancer,” he said. “That’s why we don’t wait for patients to find us, we go to them. We inform, screen, and treat wherever we can. Until enough hospitals exist, the only way to fight cancer is to take the doctors to the people.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)