As global divorce rates rise, studies show that India ranks the lowest in the world – at less than 1 per cent. Luxembourg has the highest rate, at 87 per cent, and the United States records 46 per cent.

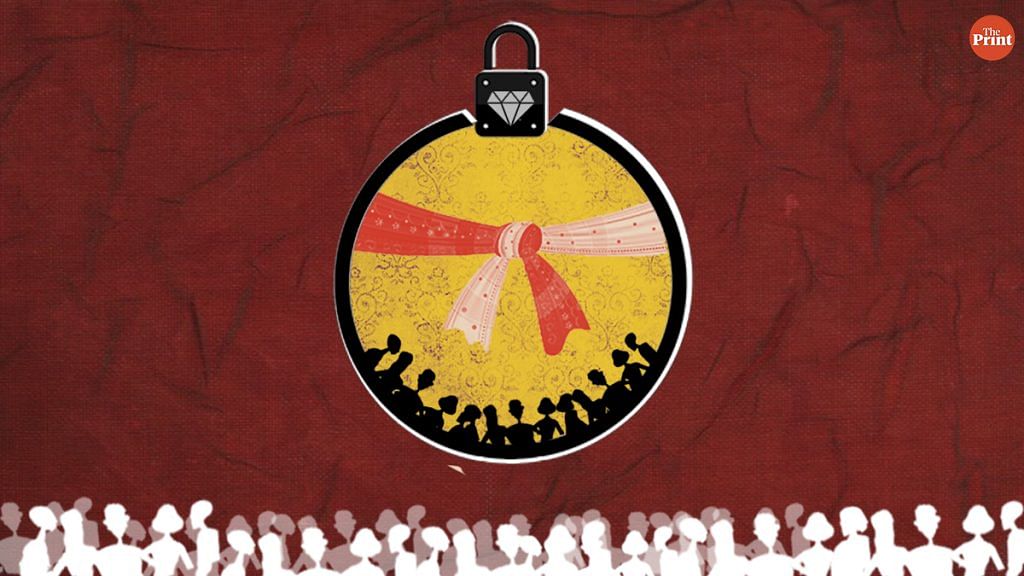

ThePrint asks: Does India’s low rank on global divorce rate indexes mean happy marriages or social pressure?

The ability to dissolve a marriage is a privilege most Indian women don’t have

Journalist, ThePrint

Out of 1000, only 13 marriages end in divorce in India. “1.36 million people in India are divorced. That is equivalent to 0.24% of the married population, and 0.11% of the total population,” said a 2016 BBC report.

On the face of it, this can be a heartening story. People in India are happily married. But here’s the caveat – most often, they are not.

For starters, most marriages in India are arranged. One agrees to spend the rest of the life with a person (and a family, in the case of a woman) one knows very little about.

The ability to dissolve a marriage is a privilege most Indian women don’t have. The reasons are both social and economic. A staggering number of Indian women are not financially independent, which limits their options severely. The social stigma of being a ‘divorcee’ is worse than being unhappily married. Then, there are children.

We have all seen unhappy marriages — from that aunt who lives with her abusive in-laws to that cook who goes home to a drunk, violent husband.

Why don’t they leave? They can’t. The ideal woman is groomed to sacrifice everything at the altar of patriarchy.

Low divorce rates don’t mean happy marriages; they just reek of a system that doesn’t allow agency or autonomy, especially for women.

The family unit is the atom in a capitalist system and a union in God’s eyes

Journalist, ThePrint

It definitely doesn’t mean happy marriages, but it’s also a lot more than just social pressure that prevents people from seeking a divorce — our entire socio-economic, cultural and political framework is built on the blueprint of the household unit.

The ‘legitimate’ family unit (read heterosexual and cis-gendered with children) is the first point of socialisation for an individual — we inherit a certain identity at birth. It’s one of the three basic economic units through which consumption and production are measured. It is the atom in a capitalist system, which requires private property to be accumulated and passed to ‘legitimate’ heirs. It is holy and sacrosanct in Hinduism — a union in the eyes of God. Any which way you look it, the boundaries of the family are fiercely protected by the institutions we have built around it. Add to this hegemonic mix, a large, all pervasive dollop of patriarchy, and you’ve found the perfect recipe for a 1% divorce rate.

Marriage is possibly the worst thing that has happened to women-kind, and men have made sure that it’s exceptionally difficult to get out of it. A legal divorce will mean alimony, possible child custody and in a lot of cases, freedom from oppressive control, and the patriarchal system just won’t allow it.

Separated couples don’t file for divorce, bringing down the rate

Associate editor, ThePrint

Divorce is still considered taboo in large parts of the country. In rural areas, the idea of divorce is still very outlandish. Although there are separations, couples often do not file for divorce legally.

Given the higher rate of arranged marriages in the country, divorces are often frowned upon because of the intense involvement of families on both sides. Family members often intervene and turn counsellors when a marriage is on the rocks. This integrated social structure, to some extent, impedes couples from taking the legal route.

Also, the lengthy legal process involved in divorce acts as a deterrent, at times. While an uncontested divorce takes anything between 7-9 months, a contested one can drag on for several years taking an emotional and financial toll on the couple and their respective families.

The social structure in India places a lot of emphasis on children. Couples are often told to have children in order to bring about stability in an unhappy marriage. So even though a couple may have separated, they often don’t formalise it. This may also be a factor in the low rate of divorce, because it goes unreported.

It’s no coincidence that married women commit highest number of suicides

Principal correspondent, ThePrint

Most Indians are conditioned to believe that individual happiness is somehow a bad, selfish thing. Women, especially, are raised to believe that the ability to compromise unconditionally for the sake of familial stability is a virtue they inherently possess. Compatibility, friendship and equality within marriages are secondary or simply alien ideas for most families. Their absence is seldom considered as a legitimate ground for separation or divorce. In fact, seeking them in a marriage is often considered an unrealistic, childish expectation.

It is no surprise that India has one of the lowest divorce rate in the world. But that by no means implies that Indian marriages are happy. It is no coincidence that married women are the highest group to commit suicide – contrary to the global trend of more men committing suicide than women.

The popular image of a doting mother, a loving wife and a dutiful bahu hides more about society than it reveals. It hides the daily humiliations and systematic corrosion of the self-esteem of scores of women in the name of familial honour and peace. It is our collective prioritisation of a façade of joy over real, meaningful happiness. While anecdotally, we may be compelled to believe that the rise of the ambitious, unapologetically assertive woman in urban India is a real phenomenon, at least for now, numbers tell another story.

The low ranking doesn’t mean happy marriages or people trapped in the institution

Web editor, ThePrint

India’s low rank on the global divorce rate index throws up some interesting thoughts. Are Indian men and women more able at steadying the boat when it gets rocky? Are Indians more self-aware now and are thus choosing more wisely? Or do traditional values dominate our DNA, no matter how liberal/modern a person is?

To cite just one reason is narrow-visioned. Why any marriage works or doesn’t is never due to one specific reason. The low ranking doesn’t mean more happy marriages or more people trapped in the institution. It’s a good mix of both.

Indians are more open to dating now; apps like Tinder and Bumble even have ads running on TV and social media. A lot more wives are able to hold jobs without husbands or families making too much of a fuss. This, in turn, guarantees a certain independence to the women.

There’s also the fact that more people are not willing to just ‘settle’ down. The pressure to be married is still there, but society is now a bit more accommodating to non-traditional set ups. Don’t worry, it still means you’ll get gossiped about if you’re living in with your partner, marry at 40, don’t have babies/adopt children, and just have a court marriage.

Marriage is anachronistic in 21st century, heaping social pressure on it even more unfair

Editor, Opinion, ThePrint

“Marriage is just paperwork for divorce,” a wise friend once said.

In India, marriages are predominantly arranged by parents, neighbours and relatives. So, everyone has a stake in making it last. Even when the marriages are not arranged, the larger ecosystem has a say in it. All of them, not just the couple, feel they have failed in some way if a marriage fails.

This kind of pressure on an institution that is anyway quite anachronistic in the 21st century is unfair. There’s a feminist saying that the institution of marriage was originally designed for ‘one-and-a-half’ persons. The woman is no longer ‘a half’, and raising children or social order no longer depends on the institution of marriage, like it once did.

More importantly, Indians measure a ‘successful’ or ‘good’ marriage in terms of its longevity. That is a fatal error.

Many married couples fight, abuse, continue heaping misery on each other, and grow apart, cold and indifferent, but stay together for the sake of families, children and finances. In fact, it is unhealthy and traumatising for children to grow up with unhappy, unfulfilled parents.

It is tragi-comic to see relatives celebrate the 50th anniversaries of such miserable marriages.

Marriage shouldn’t be made into an endurance test.

By Neera Majumdar, journalist at ThePrint.