Tweeting a GIF of an old man trying to stand up with the help of his crutch was Jofra Archer’s way of telling the world how a sensational debut centred around bowling 44 overs across two innings—the highest workload among England bowlers — at the Lord’s Test had left him bodily drained.

If his bowling left him drained, it left some of Australia’s batsmen broken, and the cricket-watching world in absolute awe. Then he did it again in the third Ashes Test at Leeds, picking six Aussie wickets in a devastating day of bowling in the first innings, and eight in total. Here is the phenomenon the game is always looking for but finds so rarely—a genuine tearaway whose fearsome pace and accuracy leave batsmen perplexed, defensive, and in danger of bodily harm. If this was boxing, Archer would be the heavyweight with lightning hands whose knockout punch opponents never see coming.

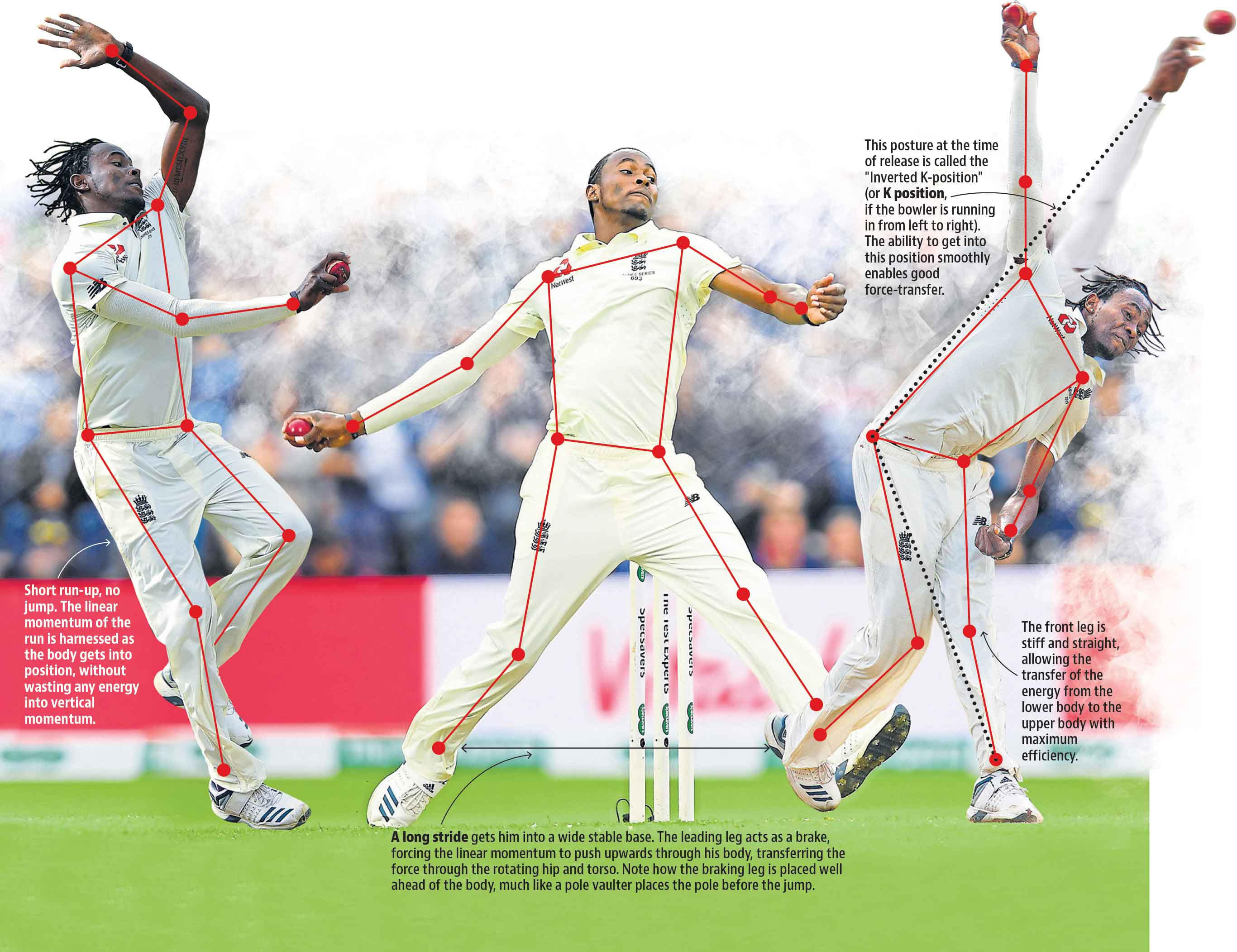

How does Archer do it? Is there something unique about him? How does he generate that speed, those variations without visible effort? With a short, languid run-up and barely a jump?

To look deeper into Archer’s bowling action, we took the help of Dr René Ferdinands from the University of Sydney, considered one of the leading experts in the world in cricket biomechanics.

Ferdinands investigates the biomechanics of fast bowling, and was one of the experts whose research helped the ICC introduce the 15-degree elbow extension leeway for defining legal bowling actions.

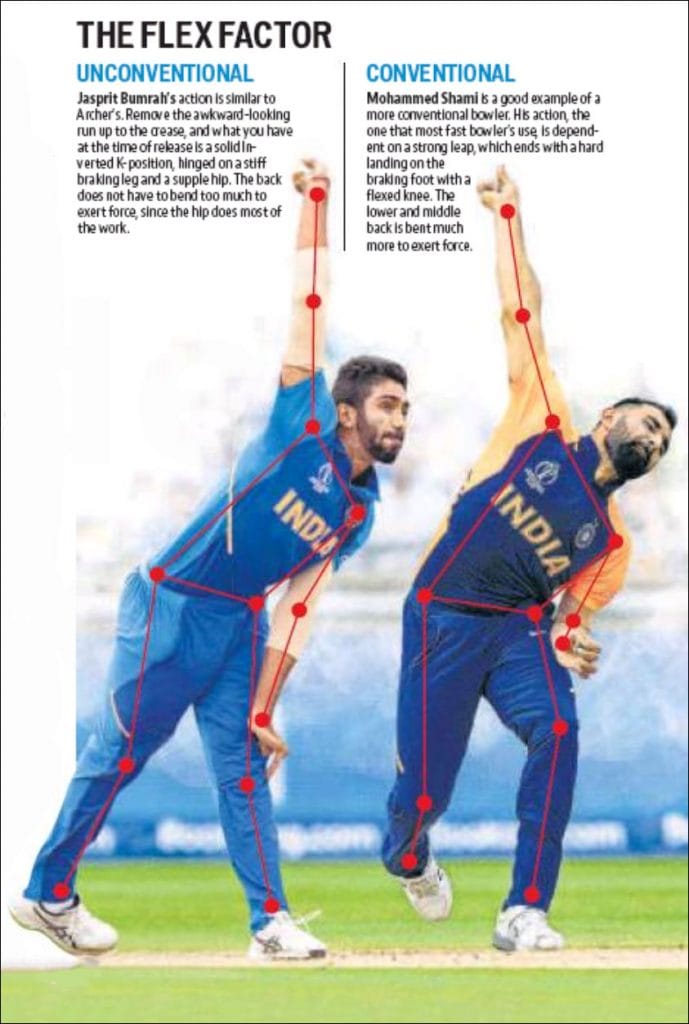

“The popular modern theory prescribes that, to bowl with maximum speed, the bowler must lift the front knee and the foot about stump high, and then whack a rigid braced leg into the ground, delay the bowling arm, pull the front arm as fast as possible into the hips and flex the trunk rapidly, while pushing the rear knee straight down the wicket,” said Ferdinands over phone from Sydney.

“I think it’s a misguided principle. There is a good case that there is more than one optimal way of bowling fast. And one such candidate is the Jofra Archer method.”

Let’s make that simpler. For conventional bowlers, the run-up creates a linear momentum that’s used to generate the leap. For the leap, the feet exert a downward force on the ground, and the ground exerts an equal and opposite force (remember Newton’s law?).

This vertical force travels through the body, through the rotation of the hips and the torso, and changes into angular momentum directed by the bowling arm and transferred into the ball.

“The really critical thing when you are bowling is to increase the linear momentum towards the batsman. If a bowler has an action that can use the horizontal momentum without wasting any momentum upwards, then that bowler could gain a mechanical advantage. Such an action, which relies more on the transference of horizontal momentum rather than on vertical momentum, does not require a high jump,” said Ferdinands.

Also read: These 5 cricketers show why size does not always matter

Momentum transfer

In Archer’s action, that’s exactly what happens. It’s what the eye sees as “smooth” or “effortless” (though there is plenty of effort involved).

His easy run-up ends with a barely lifted front knee, and a long final stride. With that long stride, he creates a wide, stable base.

Now the energy loaded into his body from the linear momentum of his run-up will begin its journey through the lower body to the upper body and finally, the ball. The key to the transfer is to rapidly decelerate the lower body by placing the braking front leg well ahead of the body, much like how a pole-vaulter places the pole prior to the jump.

“He builds up his horizontal momentum during the run-up, and then applies a very effective way of braking the lower body during the delivery stride, so that he can accelerate his upper body,” Ferdinands said.

At this point, as all of the forward momentum comes to a screeching halt with the front leg, the force travels back up through his body, through his rotating hips and torso, opening up his shoulders, and moving into his bowling arm. For that process to happen with minimum wastage of energy, the front foot needs to be rock-stable, especially at the knee joint. “If the knee bends during a period of time when the body needs to absorb some of the energy generated at front foot impact, it’s not a problem. Where you don’t want the knee to bend too much is when you are actually accelerating the upper body segments. That’s when you want the knee flexion angular velocity to be zero or constant (i.e. no increase in knee flexion),” said Ferdinand.

Now Archer is about to release the ball; all of his accelerating upper body has reached the limit of its movement, and the force has shot into his bowling arm completing its long, looping arc. His head leans over the front foot.

“It’s what we call the inverted K-position (or a K-position, if the bowler is running in from left to right),” Ferdinands said. “With a bowler who flexes the knee, there will not be such a pronounced K-position, although the head will still be over the front foot at release. In Archer’s case, he can hold that K-position for a short period of time even after the ball release. That means he has effectively used the front leg as a brake for a functionally significant period of time, enabling him to transfer a good proportion of energy to the upper body segments.”

Former fast bowler and South Africa captain Shaun Pollock concurs.

“When we did an analysis on him during the World Cup, we found there is a very big delay from when he gets into position to deliver until the right arm comes over,” he said. “That’s where he generates all his pace from.”

A 45° bend of the trunk

As Archer harnesses this efficient, supple and perfectly timed firing sequence of his muscles and joints, he relies less on the bending of the back to generate extra force, unlike most fast bowlers. At the point Archer releases the ball, Ferdinands reckons there is about a 45° bend of the trunk.

Most bowlers go well beyond that, even up to 70°. A superbly flexible and strong hip-joint serves as a perfect pivot for Archer, Ferdinands explained, unlike many other bowlers who compensate by using the lower and middle back area more as they rotate.

There is, in fact, another bowler whose action is very similar to Archer’s, though it may not look it from the way he approaches the stump—Jasprit Bumrah. “You look at (Jasprit) Bumrah as well. He is a great example,” said Warner during the third Test in Leeds.

“They are obviously all energy at the crease. Mitchell Johnson was the same. He had a slow run-up and then a thunderbolt. These guys, it takes time getting used to. It’s a rhythm thing.”

The final piece of the puzzle is Archer’s unchanged release action, irrespective of the length of the delivery. Normally, a pacer’s head tends to fall if he tries to bowl shorter since the release of the ball is late.

This is a signal that batsmen read. Archer’s deception lies in not changing the height of release at all, be it a bouncer, a yorker, or a length ball.

By special arrangement with ![]()

Also read: How the cult of Sanath Jayasuriya pulled India-Sri Lanka cricketing ties from drifting apart

Fantastic