New Delhi: With viewership in billions, surplus talent and administrative intent to harness athletes’ full potential, India has the potential to establish itself as a global sports power. There, however, still seem to be some impediments on its road to global dominance in sports, key among them being the absence of a robust anti-doping mechanism.

According to WADA’s (World Anti-Doping Agency) 2019 Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) Report, India ranks third among the world’s top anti-doping violators with 17 per cent Anti-Doping Rules violations in 2019. Russia, with 19 per cent violations, topped the list, followed by Italy with 18 per cent violations.

Doping in sports implies the use of illegal/banned substances prior to major medal events either to build more muscles or limit muscle fatigue, or effect hormonal changes to enhance one’s performance in a particular discipline. Set up as an independent body in 1999 by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), WADA was tasked with leading a “worldwide movement for doping-free sport”.

In India, the issue of doping in sports first made headlines in 1986 when three weightlifters and a boxer representing the country at the 10th Asian Games in Seoul were banned after they tested positive for doping.

Nearly four decades later, India’s anti-doping mechanism is marred by low testing, lack of awareness among athletes, coaches and trainers, and the absence of a stringent enough law.

Prominent names in Indian sports who are currently facing doping bans/suspensions include gymnast Dipa Karmakar, sprinter S. Dhanalakshmi, triple jumper Aishwarya Babu, discus thrower Kamalpreet Kaur and javelin thrower Shivpal Singh, among others.

In 2005, the Government of India formed the National Anti Doping Agency (NADA) to deal with matters related to doping in sports, but it was only in 2016 that the body got its first full-time director general (DG) and chief executive officer (CEO).

Talking to ThePrint, Ritu Sain, the sitting NADA CEO and DG, said the body has made changes in its approach to doping. “For the first time, we have gone ahead with action against a coach who indulged in doping. Time is changing and we are knocking on the right doors,” she added.

Sain was referring to Mumbai-based athletics coach Mickey Menezes who was slapped with a four-year ban by NADA in November last year, for injecting sprinter Kirti Bhoite with steroids. Bhoite was handed a four-year ban in 2020, which was later reduced.

In August last year, Parliament passed The National Anti-Doping Bill, 2021, which ensures disqualification proceedings and financial sanctions against athletes or coaches if found guilty of anti-doping violations.

On the role of NADA and doping in sports, Olympic medalist weightlifter Mirabai Chanu’s coach Vijay Sharma told ThePrint, “NADA is doing good work in terms of awareness programmes. Players at international level are well aware of doping violations and rules but it is important to increase awareness camps at grassroot level.

He added: “I also believe more than awareness, players, coaches need stringent laws against doping, so that they fear the law. The fear of consequences of the crime is missing.”

Asked what draws athletes to doping, Sharma said players “use it (banned performance-enhancing drugs) as a shortcut when either they do not train well or lack some capabilities naturally”.

He added: “Doping can get you some results which are even beyond human limits. Thus, if any player performs far better than his/her previous record, we do not clap, we rather doubt them for doping. This is the state of affairs.”

Also Read: India need not prepare extreme turning pitches to maintain home dominance in cricket. Here’s why

Testing pool & cost of testing

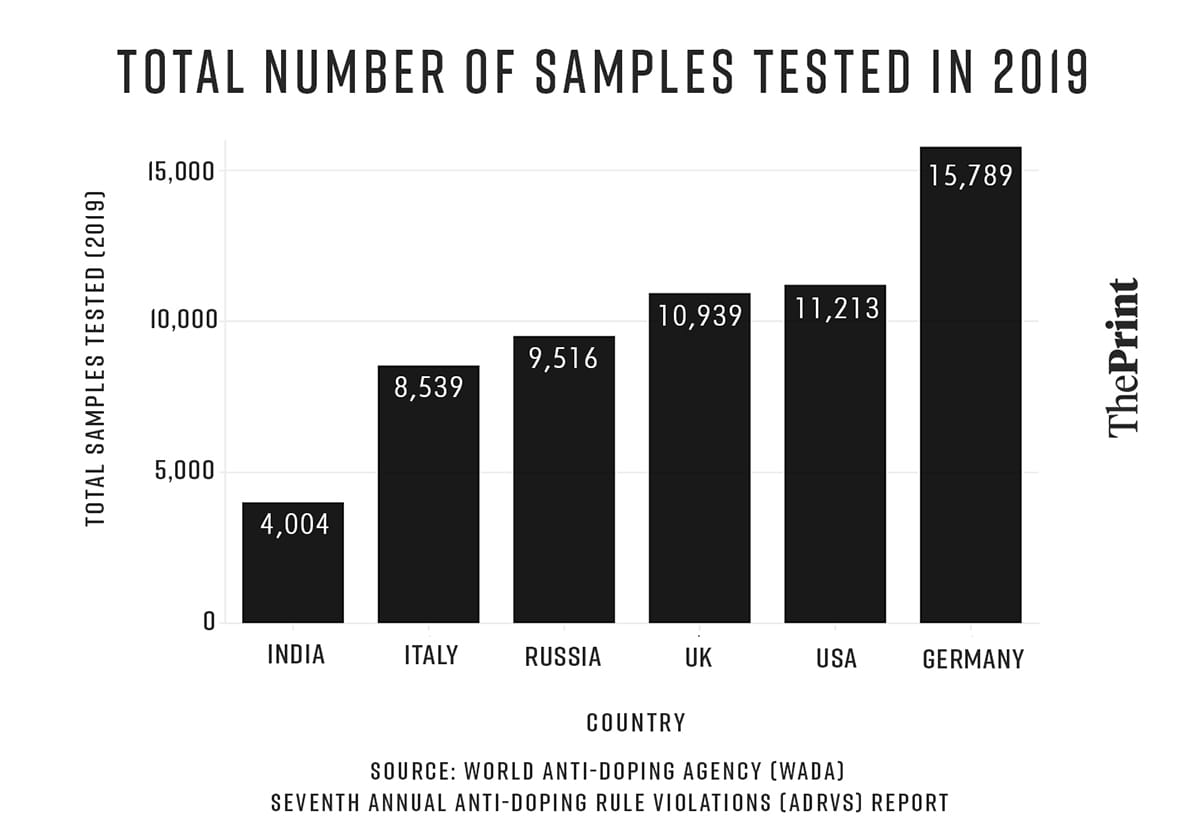

Low testing continues to be one of the key characteristics of India’s anti-doping mechanism. According to WADA’s (World Anti-Doping Agency) 2019 Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) Report, NADA tests around 4,004 samples in a year.

The data by ADRV includes testing of urine and blood samples.

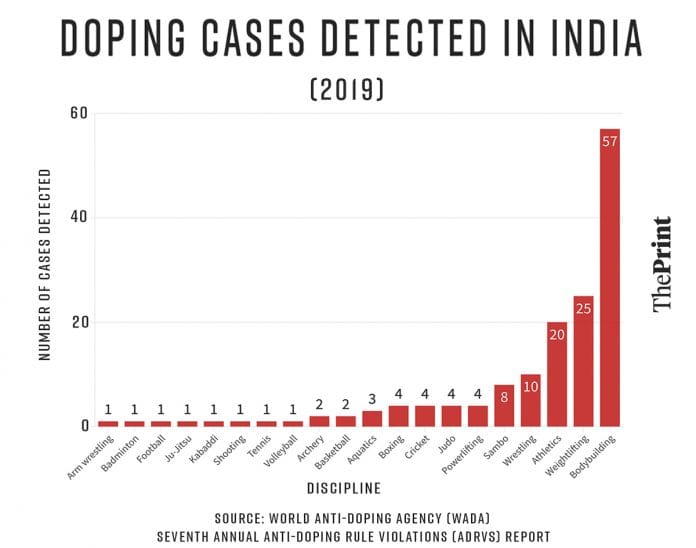

The report adds that, in India, the highest number of doping cases are reported in bodybuilding, followed by weightlifting, athletics and wrestling.

Ashok Ahuja has served for more than three decades as head of department of sports medicine and science at National Institute of Sports (NIS), Patiala.

“Only 4,000 test samples is too less a number, especially when even at domestic level competitions we have around 2,000 participants competing,” he said.

Ahuja added: “We see cases of doping as elementary at Khelo India-level, where school going kids have been found using doping products. Thus, it is crucial to increase the testing pool and expand it at domestic level competitions too. The problem is, testing at national level competitions or grassroot level competitions is too little or almost negligible.”

According to Ahuja, in most cases, athletes fully aware of anti-doping violations take the risk owing to perks that come with winning a major competition. “Since sports in India is booming and incentives range from a secure job to huge prize money, players choose shortcuts.”

Housed at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, the National Doping Test Laboratory (NDTL) is one of six WADA-accredited labs in Asia. However, NDTL was suspended by WADA in 2019 on account of discrepancies in sample results and for not complying with its standards.

Ahuja explains that this increased the cost of testing for Indian athletes since they had to send the samples to the WADA-accredited lab in Doha.

The cost of testing the first batch of samples is generally borne by NADA but if the test comes positive and he/she wants to get another test for confirmation, then the athlete has to bear the cost for subsequent tests. Earlier, urine samples were collected for tests but with advancement in techniques, athletes now have to submit blood samples.

Thus, it is not possible to cover every athlete and every event under anti-doping test drive, said Ahuja.

He added: “Even in the Olympics event, out of 10-11,000 players, 500-600 test samples are taken. So the idea is to at least expand the testing pool if not covering all.”

According to Raj Makhija, owner of Fitcart.com, a sports nutrition company which supplies to sports federations, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI ), the Indian Premier League (IPL) and hockey teams, “supplements that come from abroad are thoroughly checked with the help of third party test reports, analysis certificates but locally made products go unchecked for safety and efficacy”.

“Anyone can open and own a local supplement shop with just an FSSAI (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India) license which is granted within 10-15 days for a mere Rs 7,500 fee for a year,” he told ThePrint.

Lack of awareness, ‘wrong test results’

NADA has an Anti-Doping Disciplinary Panel and Anti-Doping Appeal Panel. The appeal panel is the highest body an Indian athlete can move to appeal against sanctions imposed by the Disciplinary Panel.

According to the 2021 Anti-Doping Rules of NADA, a player/coach/trainer may file the appeal within 21 days of an order passed by the disciplinary panel. The appeal panel is required to conclude the hearing within three months of the date of the order.

If the appellant is not satisfied with the decision of the appeal panel, he/she can appeal to Switzerland-headquartered Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS) — the highest international body for settling sports-related issues, established in 1984.

It has been observed that if caught doping, players often shift the blame on either their coach or trainer or supplement suppliers. In October 2022, when discus thrower Kamalpreet Kaur was banned, she blamed her supplements for her doping test returning positive. Kaur later admitted to the violation and the ban slapped on her was reduced.

“It is true that athletes at times take drugs to enhance their performance and even coaches support them too but at a lower level, many national players are not even aware of doping violations,” said Saurabh Mishra, a lawyer who specialises in sporting cases.

He added: “I have represented some athletes who never attended any anti-doping awareness camps and tested positive after unknowingly eating something that was a prohibited substance under WADA list. Not just that, sometimes even test results at NDTL are wrong.”

Case in point is fencer Chunni Lal and discus thrower Dharamraj Yadav, both of whom were handed four-year bans by NADA in 2019 after their samples tested positive for doping. The bans were lifted a year later when the same samples were sent for testing to WADA and the results came back negative. But by then, both had lost a crucial year of their career.

“Who will compensate for their loss? What about the career year they lost due to NADA’s negligence? The moment a player’s test comes back positive for doping, federations leave them fighting the psychological battle alone. The ideal practice is to provide them assistance in dealing with the issue legally or at least medically,” said Mishra, who represented both athletes.

There is also the case of an international-level triple jumper who claimed she took medicines prescribed by her doctor which resulted in her testing positive for doping, inviting a four-year ban. “We have filed an appeal to ADAP that the medicine she took for sickness had the banned substance and she did not take it deliberately to enhance her performance,” says Mishra, who has been representing the triple jumper — who did not wish to be named — before NADA’s Appeal Panel.

WADA’s guidelines have a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) which allows an athlete to take/use medicine which has WADA-prohibited substance, to treat an illness or condition.

Mishra explained, “Since under the act and by law, ignorance cannot be taken into account for the athlete to not fill the TUE form, even if a player claims that he/she was not aware of their legal rights and liabilities, it won’t be considered an argument. Players at international level are less prone to such mistakes than players at school/university or national level.”

A national level player who spoke to The Print on condition of anonymity said, “Even though NADA has these panels, I am unaware of my legal rights. There isn’t any rigorous awareness with respect to law in sports and we players come from such a family background, that most of us are not even that educated. Like I don’t know if there is any form to be submitted like TUE for taking medicine which has banned substances.”

But an even bigger problem, according to Mishra is that “cases take at times one or two years to resolve, whereas as per WADA guidelines, they should be resolved within three months”.

“What about the future of the athletes,” he asked.

“Educating athletes is crucial to a successful anti-doping campaign. State or national level players are more prone to using local supplements with no understanding of what they contains. Thus, awareness is important,” said Murali Shreeshankar, who won silver in the men’s long jump at the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games.

Solution: targeted testing & stringent laws

IPS Navin Agarwal, former DG and CEO of NADA (2016-2021) told The Print that when he came into the picture, he introduced an investigation mechanism to spot doping cases more structurally.

He added: “Not just that, we collaborated with our Australian counterparts to train our drug control officers and also introduced systematised testing procedures into the system. We also got the BCCI into NADA purview.”

According Mishra, NADA should go for targeted testing. This could turn out to be a cost-effective approach and will also help in achieving its target of clean events if the agency’s focus is on events that involve higher cash prize or job perks or major medal prospects.

Sain, meanwhile, said NADA has plans to launch “know your medicine mobile app by the end of this month where athletes can type the name of the medicine and get to know whether it has prohibited substances or not”.

In December 2022, NADA conducted an anti-doping training-cum-awareness camp for physical education teachers from Navodaya Vidyalayas of Hyderabad and Shillong. Earlier this year, the National Council of Educational Research and Training(NCERT) and NADA also signed an MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) to introduce value-based sports education to spread anti-doping awareness among teachers and students.

Moreover, NADA — as part of its bid to keep a check on supplements — is working with the FSSAI, Gandhinagar-based National Forensic Sciences University (NFSU) and the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education And Research (NIPER) in Hyderabad to develop enhanced testing capacity to check more supplements for prohibited substances.

NADA has also been working to fix the delay in cases before the consideration of NADA panels. Sain claims that most such cases were resolved within three months last year, adding that NADA is also trying to expand its manpower to be able to detect more doping cases and launch anti-doping campaigns more aggressively.

According to Sain, “There are two types of doping — intentional and unintentional. Intentional doping requires stringent action, which we are taking. Targeted testing and more testing have been our strategy”.

“When we talk about unintentional doping, it means a player unknowingly takes the banned substance. We have launched an intensive education program to empower athletes with the right information and awareness initiatives. We have got more than 100 educational events involving athletes, coaches and federations,” she added.

In 1928, the International Association of Athletics Federations became the first international sports body to ban doping. But it was only in 1966 that the world governing bodies for cycling and football introduced doping tests in their respective world championships. Thereafter, major doping scandals from around the world spurred bids to curb doping, like the 1998 Tour De France drug scandal which led to the formation of an independent international agency in the form of WADA.

In 2016, Germany passed an Anti-Doping Bill which criminalised doping in sports with punishment ranging between three to 10 years depending on the kind of substance in question.

The US Senate in 2020 passed an Anti-Doping Bill which allows authorities to initiate legal proceedings against those involved in doping rackets including coaches, officials, or suppliers, even if they are non-residents or if the doping took place outside the US. However, the law does not intend to target athletes but those who facilitate banned supplements.

When it comes to India, Mishra said the Anti-Doping Act, 2022 cracks down on violators, but “this menace will take longer to perish until stringent laws to criminalise doping” are not put in place.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Why India’s retired domestic women cricketers are left out of BCCI pension scheme