There will always be argument over which might be the most important or newsy year in India’s history and if you asked old reporters, each would name a favourite year, decided purely on the basis of when she broke a famous story. We reporters are like that only. Self-centred, competitive, take no prisoners, vain and a little bit crazed. I could be accused of having been all of these, particularly by those beaten on a story or two over these decades. But perhaps not even they would contest my claim that 1984 has been by far the newsiest year in India’s post-Independence history.

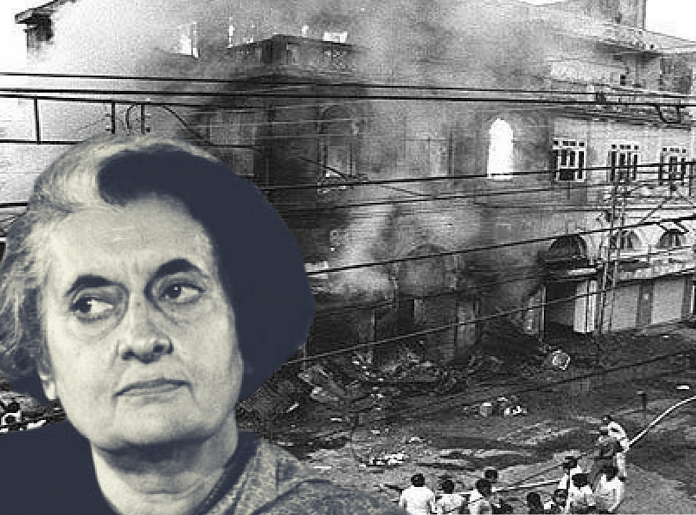

It had multiple turning points: Operation Blue Star, mutinies by Sikhs in some army units, Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the massacres of Sikhs, the rise of Rajiv Gandhi with his majority of 415 and, as if that wasn’t enough, the Bhopal gas tragedy and the Indian army’s historic ascent of the Siachen glacier. Each was a turning point and many still fester: the riots, Siachen, Bhopal.

It was the kind of year when newsrooms would feel a paucity of reporters and TV channels of OB vans. No, reporter’s vanity notwithstanding, I can’t claim that I covered each of these history-changers. I did not cover Bhopal at all, and can’t say that a transit halt on way to Jabalpur to cover the court martial of alleged Sikh mutineers would give me the right to claim the dateline. Many other stories, the elections, the anti-Sikh massacres, the assassination, consumed entire teams of reporters and all I can lay claim to is a reasonable slice of each. But a footnote: I did break the story of India’s move up to Siachen. Of course, three decades ago, the term “breaking news” wasn’t in vogue yet. I got my first opportunity to cover a big election too in 1984, and it was a trial by fire that I failed.

I was covering the Gwalior constituency where the young maharaja, Madhavrao Scindia, challenged Atal Bihari Vajpayee, whom we all so loved and believed he could never lose to an upstart. It was a genuinely sexy story. Vajpayee had gone to college on a scholarship given by Scindia’s father, his native home was just a couple of semi-pucca rooms with a kutcha courtyard and a hand-pump. In a story almost universally headlined King vs Commoner, Vajpayee was the obvious winner. So suggested inexperienced, stupid me, and was proven wrong as I have never been in calling an election. Once again, the only reporter who called even this election right was Tavleen Singh. It taught me the meaning of a wave. How it obliterates logic, reputations, history. This was so evident in this year’s elections as well, the first wave election after 30 years.

It was also, understandably, the richest year possible for old reporters’ tales. Some of stupidity (I just told you one, from Gwalior) and some of quick, life-saving presence of mind. On the first day of Operation Blue Star, for example, when you had still not realised the gravity of the intent with which the clampdown had been carried out.

Also read: Congress was involved in 1984 anti-Sikh riots – I saw & reported it

At least two of us — Brahma Chellaney and I of the three reporters who stayed behind when the army threw out the entire press corps to Delhi — probably thought we were still on some kind of riot/curfew outing on the morning of June 3, as we found ourselves in the same neighbourhood — we had never met before — along the outer precincts of the walled city. We were both drawn to the striking image of a few young Sikhs, clad in lungis, tied with ropes and being taken away by mostly six-feet-plus jawans of the Guards Regiment.

I had never seen human beings tied up like that before, and definitely not held by army jawans carrying SLRs (self-loading rifles), fingers on the trigger. I was made to regret my impetuosity just then, as a police patrol came rushing as I started taking pictures. In a state under such censorship, this is the last image anybody wanted out. Please see the picture, published on this page, and you’ll know what I mean. Now, I am glad Raghu Rai had left a camera with me (while he left for Calcutta to shoot with Mother Teresa for an American publication) and had taught me to use it too. But it did not feel like such a good idea then, as we spent maybe a couple of hours locked up in a walled city police station.

The station house officer was in a rage. “You so-and-sos (familiar expletives in Punjabi), ” he shouted, “our temple is being desecrated, the army has taken over everything, and you are taking pictures. You think this is a (expletive deleted again) tamasha?” He then threatened to shoot us and throw our bodies away and people could later decide who killed us, the army or the militants.

Both of us pleaded with him that we were harmless reporters. He flung my ID card and we soon figured out that while he was upset about the siege of the Temple, the greater provocation was the army encroaching on his turf. I tried calming him down by simply sucking up to him. We were outraged by the army operation too, I said, all Hindus prayed at gurdwaras and so on. But it was no use. This was a very angry policeman at 7.30 in the morning. I thought if we could still somehow buy a little time, simply get word across to somebody in the city that we were in this police station and alive, it would make his death sentence less untenable. Brahma was more idealistic, honest and courageous.

“Under which law are we being held?” he asked the cop with the permanent frown.

“Kanoon! Ai lo ji, eh puchhda kehdi dafa de andar phadia hai ehna nun (Law! He wants to know under which section have we caught them),” he said with a smirk and then turned to one of his minions, “Dassin bhai ehnun tun (Why don’t you tell him)?”

And before the minion could answer, he said, just shoot them and throw a couple of kilos of opium on their bodies, that will suffice, or maybe a pistol each, there are some kept only for this purpose. And then, in a turn straight out of a latter-day Vishal Bhardwaj/Anurag Kashyap movie, the minion woke up in alarm.

“Opium is quite enough, SHO saab bahadur, why are we wasting pistols, we don’t have that many and we keep needing them again.”

It may sound funny now, but wasn’t so then. I don’t know about Brahma, but I was very, very scared. What this exchange had done, however, was lighten the atmosphere just a bit as all the cops joined in the derisive banter. Brahma, in fact, was still protesting, ignoring even his driver who tried to calm him. I continued to beg to be allowed to use the phone just once, to call “Mr Aulakh, who is expecting to see me in his office at this moment very urgently, Aulakh saab, the head of the Subsidiary Intelligence Bureau (SIB) in Amritsar.” It was a complete bluff. M.P.S. Aulakh was indeed the IPS officer who headed the SIB there, he knew me well — we had even been neighbours briefly in Chandigarh — and I thought if it could impress the SHO into letting us make just that one call to him, it may save our lives. Name-dropping, pulling rank, are also legitimate reportorial tactics and after a while, it worked. Even the furious SHO did not want to override the possible wish of a senior IPS officer, particularly as everybody in the local police knew and respected him.

I called Aulakh’s home and his wife picked up. I told her an utter lie: that Aulakh must be waiting for us in his office for an urgent discussion but we were caught up in some disturbance, and now being looked after at police station division such-and-such. She understood the situation and was quick to call her husband. Five minutes later, the phone rang, the SIB office told the SHO we were needed by Mr Aulakh and that a Jeep was on its way to fetch us. That is where all the excitement ended, though I did get a gentle scolding from Aulakh later. The Aulakhs now live in retirement at their small country home on the outskirts of Chandigarh and I can now also reveal that the IB officer I mentioned in the second part of this series, who told me with dismay how his warnings to not underestimate the militant firepower or resolve in the Temple went unheeded, was none other than Aulakh, one of the finest intelligence officers I have travelled with in my journey as a reporter. Besides, indeed, being a life-saver gifted with a wonderful, generous and quick-witted sardarni.

Also read: 33 years ago, this day: burning flesh, smoking city, a nightmare lived—and reported

People are as central to reporters’ lives as money or cheque books to a banker or businessman. People are the capital of our working lives. Except, unlike any currency or most assets, they mostly become more valuable over time. And it is uncanny how they keep resurfacing in your lives. That’s why I had promised some “people” stories today.

I still cannot reveal the source of the Siachen newsbreak, the fact that our army had moved on to desolate heights in what was codenamed Operation Meghdoot, the eternal story of the world’s highest battlefield, which has defied solution for three decades now. But I can tell you about the two key commanders involved. Lieutenant General M.L. Chibber, then GOC-in-C, Northern Command, and Lieutenant General P.N. Hoon, then GOC, 15 Corps, Srinagar, and later director general of military operations (DGMO). I got a ringing admonition from him later when I went to see him to check on a follow-up story and addressed him as DMO, the old title for the job: “I am no bloody DMO, I am DGMO, young fellow.”

Both were proud of moving on to Siachen and beating the Pakistanis, who had apparently planned a similar operation, and each claimed he had played a more important role. In fact, when I somewhat breathlessly suggested to Hoon that it looked like we had outflanked the Pakistanis in a couple of chases to the top, he straightened in his chair in some alarm: “Outflanked? Who told you that word, outflanked? That was the word I used to plan my strategy.” Oops, I think now, I should have known I was looking at one of the future prime-time stars of the shouting channels decades later. Hoon later became a real hawk, even joined the Shiv Sena once. Chibber, on the other hand, became one of India’s foremost peaceniks and set up an NGO to talk peace with Pakistan. You never know what growing out of the uniform can do to you. Both continued featuring in our lives as reporters for decades.

As did General K. Sundarji, though in a very different manner qualitatively. After Blue Star, he became one of our most dashing and futuristic chiefs, shifting the entire outlook and doctrine from defensive to offensive, attack-and-halt to assault-and-keep-moving, terrestrial to airborne, pedestrian to mechanised. No other chief has left behind such an abiding doctrinal legacy in India’s history. He became one of my favourite people over the years, he indulged me greatly too (you may want to see the obit I wrote on him: ‘Soldier of the mind’, IE, February 10, 1999, iexp.in/wMG89512). But I had started with him on a really embarrassing note.

In my coverage of Operation Blue Star, which drew wide international notice, I had made what would be an inconsequential mistake for any civilian but was a truly idiotic blunder for someone with claims to being a defence reporter. I had made the mistaken assumption that the 25-pounders used by the army to maul the Akal Takht had fired in trajectory mode. What that would mean is guns firing almost vertically upwards and the shells then following a parabolic trajectory to hit the target. I described the risk it involved in a crowded locality and how brilliant our gunners were that hardly any strayed despite the summer breeze. It was just a hyped compliment to our gunners, but embarrassingly wrong. The guns had fired in the direct mode and from a very close range. Many soldiers pointed this out to me but none as rudely and colourfully as Sundarji. “Ha! You defence reporters,” he said, “You can’t even tell the difference between bore and calibre.” And then, turning the knife even as he laughed, enjoying his own joke, “You can surely be big bores despite having low calibre.”

We became friends, fellow travellers on the strategic conference circuit and he even wrote a column for me that I pleased him very much by naming “Brasstacks” (the codename of his controversial exercise that nearly took us to war with Pakistan in 1987). But he never stopped repeating that lesson on gunnery to me.

Reporters’ lives are rough, chaotic but fun. Which creates justification for a lot of excess. Overeating, some drinking, no exercise and smoking (though not that last one in my case). In the summer of 1984, therefore, I weighed 83 kg (73 now). One of the fittest members of the hack-pack was always Satish Jacob, Mark Tully’s much-loved deputy at the BBC. We first met in Assam in 1983, when he was covering the aftermath of the Nellie massacre. He immediately told me I had to learn to exercise and by the time action was peaking in Amritsar, brought me from London my first pair of running shoes, an Adidas. You couldn’t get athletic shoes in India then and by teaching me to run, Satish added several energetic years to my life. As far as Satish and I are concerned, our fitness connection has just entered the fourth decade. His Bosnian daughter-in-law, Vesna Tericevic Jacob, is among Delhi’s topmost trainers, mine too, and isn’t she unforgiving!

In early enthusiasm, however, you can even overdo exercise, and in different ways. Like they say for the neophyte mullah chanting Allah’s name all the time, I wanted to run all the time, including under the burning late-afternoon sun on Amritsar’s curfew-bound, empty, tree-lined streets. One such afternoon, on Day 5 of Blue Star, I froze as a small convoy of machine-gun mounted Jeeps appeared from around the bend, and jawans jumped out, rifles in firing positions. And then I heard a comforting, familiar voice, “Oye yeh toh Shekhar hai, tere saare baal hi jhad gaye teen saal Northeast mein (Oh this is Shekhar, you’ve lost all your hair in three years in the Northeast)?” It was my friend and next-door neighbour from my bachelor annexe in Chandigarh’s Sector 33, Amarjeet Dhesi. A major in 12 Guards (anti-tank missiles), he played serious hockey, a game I loved watching. Further, he was a nephew of Balbir Singh Sr, India’s triple Olympic gold medalist, now listed by the IOC among the 16 greatest Olympic athletes ever, along with the likes of Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis. He introduced me also to another fellow major, tall, strapping, with a missile badge on his chest, along with his name, Tejinder. He is Lieutenant General Tejinder Singh, who resurfaced in our lives two years ago when the outgoing army chief accused him of trying to bribe him and he responded by suing him for libel. I caught up with Col Dhesi, who now lives in California, last winter, where else but in Chandigarh, at his uncle Balbir Singh’s home as I went to record a Walk the Talk interview with that greatest living Indian sportsman, now a lively 91, and one who should have got the Bharat Ratna before many others, even if one of them is called Sachin.

Also read: 72 Hours, 21 Years

If you are still not convinced that people keep coming back in reporters’ lives, usually more importantly than before, and that we need to preserve our notebooks and memory, think about a Kingfisher flight from Delhi to Mumbai about five years ago. There was only one other passenger in the front cabin sitting across the aisle from me, and I thought he looked familiar. He had a weather-beaten face, tough, firm, broad-shouldered demeanour and soldierly countenance, even as he pored over what looked like a sheaf of Excel sheets. We exchanged some where-have-I-met-you-before glances and then he broke the ice. “I bet you won’t remember me, but I haven’t forgotten,” he said.

He asked me if I recalled that in 1981, in Aizawl, I was bitten by awful dim-dam flies and a CRPF patrol had taken me to their company sickbay for treatment. His name is Balwan Singh Gahlawat, and he commanded that company. Then he asked if I remembered unauthorisedly hanging out at a camouflaged and fortified medium machine-gun nest on the top of a building in Amritsar’s Braham Buta Akhara, overlooking the Golden Temple during Blue Star. He was now the commandant of that CRPF battalion providing the assault troops covering fire. “And you must be wondering what am I doing sitting here on this plane, ” he asked, with a smile.

He said his sons had set up a business in Mumbai and he goes there often to help them out, particularly as they also have large property developments.

“What business do your sons run?”

I asked.

“India Bulls, ” he said.

Of the many days spent on the pickets in that story-studded year, one particularly endures. Having realised the stupidity of a media clampdown in Punjab, the army had now given me permission to go and witness the GCM (general court martial) of alleged Sikh mutineers (following Blue Star), in Jabalpur cantonment.

Nobody put any restrictions, nobody censored anything. It was like any other court hearing, albeit with uniformed officers. One uniformed “mutineer” after another was seated on a chair in front of judges and lawyers. Each, very young, innocent, shaken and contrite, each with the same story. That in his unit far away from home, he heard rumours that all young male Sikhs were being slaughtered, women being mass-raped, gurdwaras desecrated and destroyed, the Golden Temple reduced to rubble. There was no way of checking, no one to believe, nobody trusted Doordarshan or even the newspapers. Actually, most of this was fiction. Even the Golden Temple stood more or less unscathed, barring some stray bullet holes, though the Akal Takht and much else had been destroyed. But it confirmed yet again, if any confirmation was needed, that nothing harms a society and a nation more than a deliberate denial of truthful information to its citizens, particularly in a period of trauma. It leads to a tragic situation where all rumours are seen as true, and the worst rumours the truest. And that leaves an angry, isolated soldier with little option other than to pick up his rifle, march on Delhi and shoot anybody who tried to stop him. I know nothing can justify mutiny in any army, but these hapless boys were not the only ones to blame in 1984.

Also read: During 1984 riots, even Manmohan Singh’s family home was about to be burnt down