Bengaluru: Saturn’s largest moon Titan may harbour surprisingly deep lakes filled with methane atop hills and plateaus in its northern hemisphere, data from the Cassini mission has revealed.

A joint initiative of the United States’ NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, the Cassini mission ended in September 2017.

The new findings are published in the journal Nature Astronomy as two papers.

That there are larger ‘seas’ of methane on Titan has been a known fact, but finding smaller lakes and lake systems that are not only deep but also at high elevations reveals more about the geology of the moon than previously known.

Titan, one of over 60 Saturn moons, is the only other body in the solar system to have a liquid cycle like the Earth’s water cycle: Methane and ethane rain down and evaporate to form clouds.

On Earth, these are gases, but on frigid Titan, the temperature is low enough for them to exist as liquids on the surface.

Titan is, in fact, the only other body in the solar system to have liquid on its surface.

As on Earth, the flow of these liquid hydrocarbons has carved out geological land-forms. Titan has rivers, seas, mountains, plateaus, lakes, and more, as if it were a shrunk Earth.

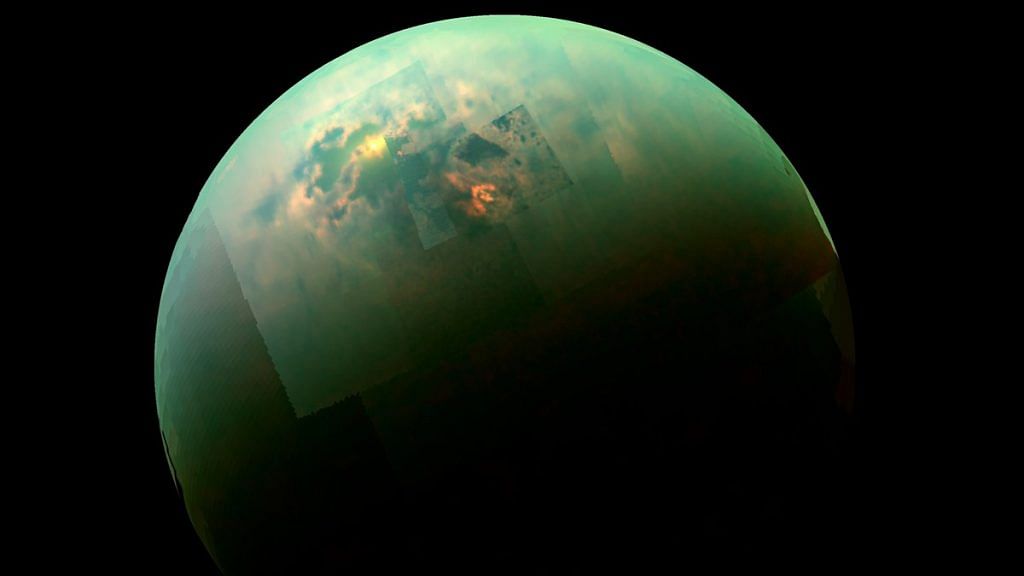

Titan is about twice the size of our moon. It is enveloped in a dense cloud of atmosphere, which makes it the only moon in our solar system to have one.

The air primarily comprises nitrogen with methane and ethane in smaller quantities. The moon even sees seasonal changes in weather, and retains an average surface temperature of −179.5 °C.

Also read: First private landing on moon fails as Israel’s Beresheet lander crashes

Digging deeper

On its last closest approach to Titan, on 22 April 2017, Cassini flew over the northern hemisphere of the moon and fired up its radar to probe the depths of the lakes there for the first time.

Scientists have earlier measured Titan’s seas, but the specific details of the northern lakes were unknown.

Cassini’s inspection revealed large seas with low elevation, islands in the middle, and large canyons on the eastern side, and small lakes of liquid methane at high altitudes, on top of several separate high hills or buttes, on the western end.

Radar data revealed that these lakes were surprisingly deep, more than 100m. The findings also suggest that Titan may host yet another feature similar to Earth: Caves. On Earth, these are formed when water erodes rock, and scientists believe the same is possible on Titan as well.

This argument is bolstered by the detection of Titan’s high-altitude lakes, which were likely created when rock forms caved in and created craters for the liquid to settle in.

Seasonal changes

Scientists also discovered three lakes with exposed beds, called ‘phantom lakes’.

These are similar to exposed shorelines earlier observed in the southern hemisphere of Titan, which are believed to have been caused by the seasonal evaporation of liquid methane.

One Titan year, which is also one Saturn year as the planet goes around the sun causing seasonal changes on the moon, is equal to 29.5 Earth years. One Titan day is one rotation of the moon, which takes 15 days and 22 hours. As the moon is tidally locked, a single revolution of Titan around Saturn also takes the same time.

The dryness of the phantom lakes indicate that there are also shallow ponds in the northern region along with the really deep lakes that last as liquid through colder seasons. These lakes that change seasonally are called transient lakes.

What makes these findings interesting is that Cassini, which reached Saturn in 2004 and flew by Titan, had earlier spotted these liquid lakes. The lakes had dried up by the time the craft returned to the site.

Radar and infrared data from these northern lakes show that even these lakes undergo long seasonal changes over a period of three decades.

These findings support the theory that methane rain feeds lakes, which then both evaporate back into the atmosphere as well as seep through the soil, creating vast underground reservoirs of liquid hydrocarbons.

Also read: The world gets its first look at a black hole. Here’s how we got there