A team of researchers at IIT Hyderabad has combined the power of four algorithms to yield clear answers at great speed.

Bengaluru: A trick developed by researchers at IIT Hyderabad promises to sift through tons of noises in the universe to identify key data points in a jiffy, and thus help scientists unlock some more mysteries of the infinite expanse.

The IIT Hyderabad team’s machine learning method can help identify pulsars from astronomical scans of the sky at least 10 times more efficiently than astronomers do today.

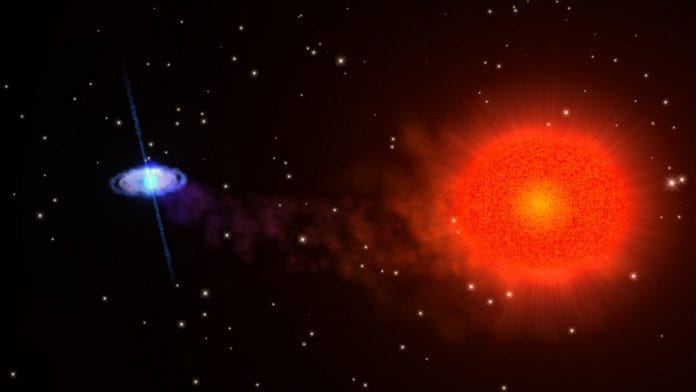

Pulsars, spinning neutron stars that emit pulses of radio waves at regular intervals (imagine a lighthouse), act as reference points and are used to understand other complex phenomena in the universe.

Also read: Jargon-less research is latest ISRO tool to bring the universe to our living rooms

Their emission is often precise enough to rival atomic clocks, and they can be used for timekeeping for satellites, as well as for the accurate positioning of spacecraft.

They also help in exoplanet detection, and acted as the guide for the very first discovery of a planet outside our solar system in 1992. Pulsars helped detect the very first gravitational waves as well.

With the help of computers

While humans had observed and catalogued 2,613 pulsars as of April 2017, it is estimated that the number of observable pulsars could be over 100,000 in our galaxy alone.

Today, detecting and searching for astronomical phenomenon has become the work of computers. Manually scanning through telescopic data is an intensive and time-consuming exercise.

That is why algorithms that help identify patterns in large quantities of data are periodically developed and improved, making our science more accurate.

Also read: India wants to build a computer 10,000x faster than today’s best, and beat China to it

However, most algorithms in use today throw up millions of potential pulsars, from which astronomers pick out the genuine candidates after eliminating thousands of other radio sources.

The method devised by the IIT Hyderabad researchers — a combination of four machine learning algorithms — dramatically increases the rate and accuracy of pulsar detection. The four algorithms are the Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Adaboost, Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), and XGBoost; the ANN being the only one in use currently for machines searching for pulsars.

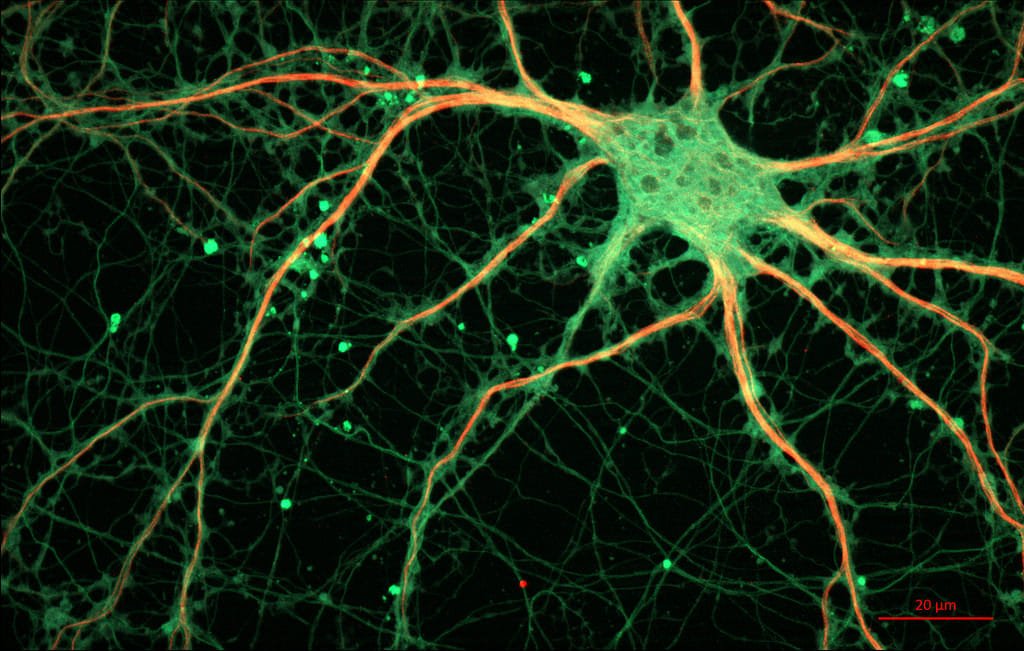

Inspired by the human brain

ANN draws inspiration from how human brains work, which explains the name. The network of algorithms is made up of ‘neurons’ that are layered and stacked till they are all connected, mimicking the human brain.

Each algorithmic ‘neuron’ is responsible for taking an input, processing it, and providing an output. Using this algorithm to sift through sky survey data to identify pulsars would take an average of 300 seconds per candidate, which means over 80,000 human hours, or roughly 10 years would be required to identify 100,000 pulsars.

Two of the other algorithms, Adaboost and GBC, use a flow-chart like approach.

“One starts at the top of the flowchart and lets the data answer the questions at every point of the flowchart which determines where to go,” said Suryarao Bethapudi, lead author of a paper on the findings that was published earlier this year.

“For instance, if the data has many positive values, go right; otherwise, go left,” he added, “This traversal is done until the end of the flowchart is reached, at which point a decision is made.”

The fourth algorithm, XGBoost, is a combination of these two types.

Using their techniques on a sky survey set that had led to the discovery of pulsars four years ago, the researchers were able to drastically bring down the number of false positives (i.e. radio signals that are shortlisted as pulsar candidates).

To decode old research

For the researchers, their study offers the hope of tantalising answers about the universe.

“What if all the pulsars discovered until now are just small-scale celestial labs?” Bethapudi told ThePrint on email. “What if we discover a pulsar that shows all the pulsars studied until now to be just ‘regular’ pulsars? We could grasp insights that would revolutionise our understanding.”

The IIT Hyderabad algorithms can be applied retrospectively to existing sky surveys to identify pulsars that might have been missed earlier.

Also read: First moon outside the solar system found. It’s the size of Neptune.

“If a dataset from another pulsar survey is readily available, we can immediately apply our methods to it,” said Shantanu Desai, co-author of the paper. “Our codes for this analysis have been made publicly available. We hope that other pulsar researchers will notice our work and apply these algorithms.”

In fact, this method doesn’t necessarily need to be limited to identifying pulsars.

“The versatility of machine learning is that the same algorithm can be trained to work on different datasets to solve different problems,” said Bethapudi, citing as an example fast radio bursts (FRBs) discovered in 2007 from a 2001 data set. A flurry of papers on new pulsars and FRBs is to be expected in the near future, he added.