Bengaluru: On the morning of 16 July 1945, a blinding light tore through the still-dark sky over the Jornada Del Muerto desert in New Mexico. It was the birth of the Atomic Era, but theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s response was a curt, “I guess it worked”— at least according to his brother Frank Oppenheimer.

Years later, in an NBC news documentary, Oppenheimer recited a line from the Bhagavad Gita when talking about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

This powerful and chilling quote features twice in Christopher Nolan’s 2023 biopic of one of the most celebrated and vilified scientists in history. But the movie Oppenheimer is not just about Oppenheimer. It also illuminates the evolution of the Manhattan Project and the alliance of brilliant minds working to create the world’s first atomic bomb.

Overall, it’s the story of an era when World War-II ignited a race to harness the atom’s hidden power after the discovery of nuclear fission by German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman in 1938. For all its destructive capabilities, or perhaps because of it, the atomic bomb became a symbol of power.

Just as artificial intelligence and quantum mechanics are central to the current scientific epoch, the exploration of atomic energy and nuclear fission powered the science of the 1940s.

But the film’s gaze, focused on Oppenheimer, offers only glimpses of his scientific contemporaries —some, recipients of the Nobel Prize— whose contributions were pivotal to shaping the course of modern physics.

Its lens also did not capture parallel developments on the other side of the globe in India, where Homi Bhabha was leading the country’s quest for atomic energy.

In 1948, for instance, Bhabha had urged Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru that the development of atomic energy be “entrusted to a very small and high-powered body composed of say three people with executive power, and answerable directly to the Prime Minister without any intervening link.”

Here’s a look at some key figures from the atomic era, some portrayed in the film and others whose roles remained beyond its scope.

Also Read: Oppenheimer — ‘father of atomic bomb’ swore by Gita, put it all at stake to oppose hydrogen bomb

A rough start

Robert ‘Oppie’ Oppenheimer (played by Cillian Murphy) was born into a wealthy New York Jewish family in 1904. After getting his undergraduate degree in chemistry from Harvard, he went to Cambridge University to study physics.

He did not see instant stardom. As shown in the movie, he was so bad at experimental work that he was miserable. It was also in Cambridge that he met soon-to-be Nobel laureate Patrick Blackett (James D’Arcy), featured in the movie as the professor he tried to poison with an apple. While no one ate the apple, his mischief became known and his parents had to convince authorities to not press charges.

Notably, Homi Bhabha, later to be known as the father of the Indian atomic programme, studied in Cambridge in the late 1920s, and worked at the Cavendish lab, which Oppenheimer wanted to join.

But Oppenheimer left Cambridge battling severe depression and in 1926 moved to Germany where he completed his PhD in physics. He was 23 years old, and Europe was still uneasy in the aftermath of the First World War. Mussolini had seized power in Italy and Hitler was just rising in popularity in Germany.

Early encounters with friends & foes

During his stay in Germany, Oppenheimer cultivated relationships with several fellow colleagues, some of whom would become future collaborators.

Among them was Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi (Danny Deferrari). While he joined the Manhattan Project relatively late, he played a role in selecting Japanese targets. In the 1930s, Bhabha also collaborated closely with Fermi while he was on the Isaac Newton scholarship in Rome.

Significantly, it was Fermi who alerted military leaders to nuclear energy’s potential and is renowned for creating the first nuclear reactor. He won the 1938 Nobel Prize for his work on radioactivity and discovery of transuranium elements— the synthetic element fermium is named after him.

Like Oppenheimer, Fermi opposed the development of hydrogen bombs. He defended Oppenheimer in the security hearing in 1954 when the latter was accused of being a Soviet spy during the McCarthy era.

Oppenheimer also became close to Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), a German theoretical physicist whose legacy includes the uncertainty principle and the 1932 Nobel Prize for “creation of quantum mechanics”.

However, Heisenberg was also the principal scientist in the Nazi nuclear weapons programme during World War-II, and contributed to West German nuclear reactor development.

The movie shows Oppenheimer’s team in a race with Heisenberg’s to develop the bomb, but in reality, Heisenberg never came close to success on this front. In fact, it is believed that conscientious German scientists secretly sabotaged the research.

Heisenberg, notably, spent time in India in the 1920s as a guest of Tagore, indulging in deep discussions about philosophy, life, and science.

In Germany, Oppenheimer also became friendly with Hungarian-born physicist Edward Teller (Benny Safdie), whose calculations were often referred to in the movie. The relationship between the men, however, eventually soured.

Teller and Oppenheimer disagreed about the type of weapon to prioritise in the Manhattan Project. Teller was a proponent of developing hydrogen bombs, and, in fact, came to be known as the father of the hydrogen bomb. In the closed-door hearing, he testified against Oppenheimer.

Onscreen, Teller can be easily identified by his sweaty eyebrows. He is the person with whom Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty refuses to shake hands.

Another member of Oppenheimer’s circle in Europe was Polish-American physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi (David Krumholtz). In the film, Rabi is featured in a scene where Oppenheimer is about to give a lecture in Amsterdam. Rabi offers to help a Dutch scientist translate Oppenheimer’s lecture into English. However, Oppenheimer surprises everyone by speaking in Dutch himself, a language he learned in just a few weeks.

Rabi was a lifelong friend of Oppenheimer, and in the movie, he is the only one who talks about Oppenheimer’s religion, addressing it in the train scene. He won the 1944 Physics Nobel for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, which is used in MRIs today. His work also led to the development of the microwave oven.

Return to America

When Oppenheimer returned to the USA in the late 1920s, he received job offers for professorships at both UC Berkeley and Caltech. He opted for the position at Berkeley while also taking on a visiting teaching role at Caltech.

At this time, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and spent time at a New Mexico ranch to recover. He fell in love with the region, where he had also been sent as a teenager to recover from dysentery. It was here that he would later set up his secret Los Alamos laboratories.

In Berkeley, in the 1930s, he worked with another Nobel Prize experimental physicist, Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett). Oppenheimer was introduced to the Manhattan Project through Lawrence, who later became an H-bomb proponent.

In the early days of their relationship, Oppenheimer and Lawrence were very close, with the latter even naming his son Robert. The two fell out later due to political disagreements, but Lawrence refused to testify against Oppenheimer in 1954.

Meanwhile, what is now called the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen had become another big hub for theoretical and nuclear physics research in the late 1930s. Here, Homi Bhabha worked with the likes of Wolfgang Pauli, Hans Kramer, Enrico Fermi, and, of course, Neils Bohr (Kenneth Branagh) himself.

Bohr, who discovered the internal structure of an atom and showed that electrons orbit the nucleus, was involved with the Manhattan Project only for a short time, but is known for his work on quantum theory, for which he won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physics. He was involved in the establishment of CERN. After the war, he became a proponent of international cooperation on nuclear energy.

Bohr had visited India on a couple of occasions, upon the invitation of physicist Alladi Ramakrishnan, who had him deliver lectures in Chennai. Bohr was particularly taken with the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), and was very supportive of the Indian nuclear research programme.

In the movie, he can be seen handling the poisoned apple, which was not intended for him, and asking Oppie to listen to music instead of reading sheet music.

Communism, a car named Garuda, marriage

Many of Oppenheimer’s political and spiritual beliefs coalesced in the years leading up to World War-II.

In the early 1930s, his interests expanded to encompass languages, myths, and religion. Mesmerised by the Bhagavad Gita, he learned to read Sanskrit and even named his car ‘Garuda’ after the divine vehicle of Lord Vishnu.

Through this decade, Oppenheimer studied cosmic rays, nuclear physics, quantum electrodynamics, as well as relativity and astrophysics. However, the onset of World War II in 1939 forced many scientists, including Homi Bhabha, to return to their home countries.

By this time, Oppenheimer had adopted many ideas for social reform that came to be categorised as communist. While he never was an open member of the Communist Party of USA, he donated money through communist channels for social causes.

In the film, Oppenheimer’s wife, Katherine “Kitty” Puening (Emily Blunt) is depicted as testifying to this effect during her hearing.

Kitty, whom Oppenheimer met in 1939, was a huge influence in is life and remained by his side until his death. A German-born American botanist, she was a former member of the communist party.

Before Oppenheimer had even joined the Manhattan Project, an FBI file was opened on him in 1941.

Also Read: Sabotage or accident? The theories about how India lost nuclear energy pioneer Homi Bhabha

Manhattan Project kicks off

Oppenheimer’s work in quantum mechanics and nuclear physics had caught the eye of many scientists, and his ability to be an informed liaison between scientists and defence forces led to General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) handpicking him as a “genius” to lead the Manhattan Project. The two are often credited together for producing the world’s first atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer started off by holding a summer school for bomb theory in Berkeley, involving many of his colleagues and students, including Robert Serber (who was romantically involved with Kitty after Oppenheimer’s death) Teller, and German-American theoretical physicist Hans Bethe (Gustaf Skarsgård).

Bethe was personally asked by Oppenheimer to join the Manhattan Project and oversee its theoretical division. He is best known for his work at the confluence of astrophysics and nuclear physics, winning the 1967 Physics Nobel for his work on stellar nucleosynthesis, the process by which heavier elements are created in stars.

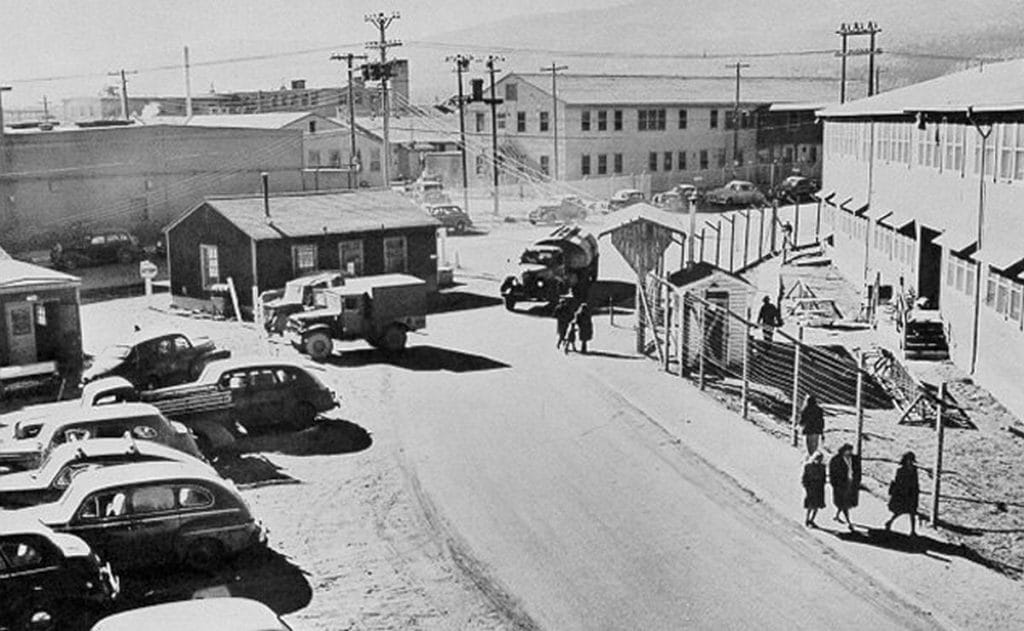

In 1942, the plans for a secret lab in Los Alamos were in place. The US military notified the local Indian tribes living in the area that they had 24 hours to vacate, and usurped the land.

Set up at the Los Alamos Ranch School, the Manhattan Project grew from 1943 to 1945 to include thousands of people. Oppenheimer ran the project efficiently, and was noted for his administrative ability among scientists and military personnel.

At the same time as the establishment of Los Alamos in US, a premier institute of research was being established in India. At the time, Bhabha was a professor at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore (now Bengaluru), and was working with JRD Tata and Nobel laureate Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar to establish TIFR in Mumbai.

‘The world will never be the same again’

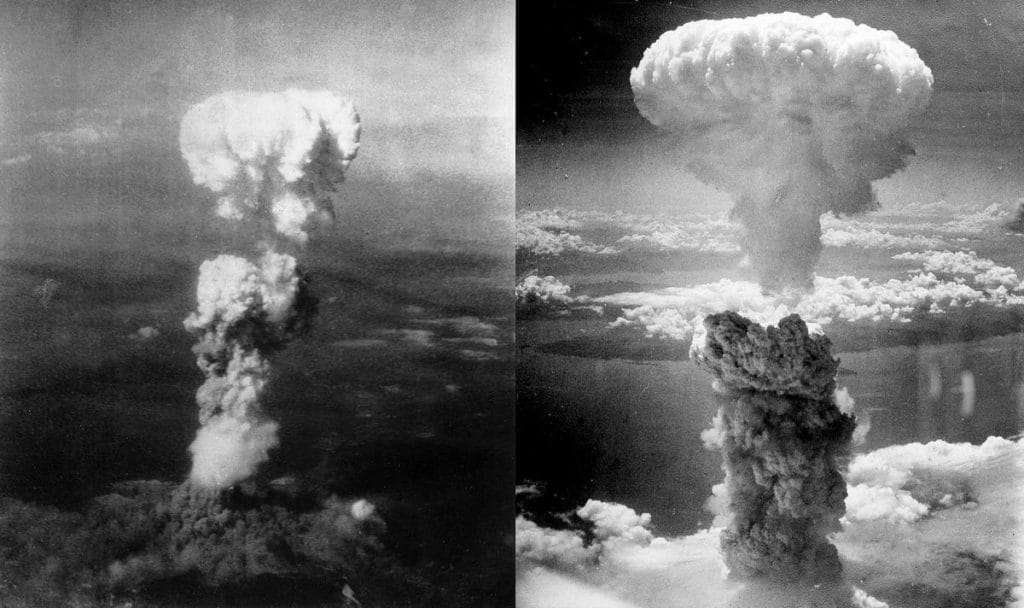

In 1945, the Trinity test marked the world’s first atomic bomb trial, and the first occurrence of a mushroom cloud.

Richard Feynman (Jack Quaid) claimed to be the sole person to witness the test without protective glasses. The famous (or infamous) physicist was a graduate student when he joined the Manhattan Project, Feynman contributed to safety protocols for uranium storage. His work in quantum electrodynamics earned him the 1965 Physics Nobel.

After the test, Oppenheimer famously remarked that the world would never be the same again.

Indeed, the Trinity test released nuclear fallout into the atmosphere, which continues to persist today and has contaminated modern steel. This led to the use of “low-background steel” or pre-Trinity steel in modern physics experiments and radiation-sensitive devices like Geiger counters. Sunk WWII submarines have long been illegally scavenged for their pre-war steel.

Moral doubts & Szilárd petition

After the test, as shown in the movie, some scientists at the project began to express their moral qualms about dropping the bomb on civilians.

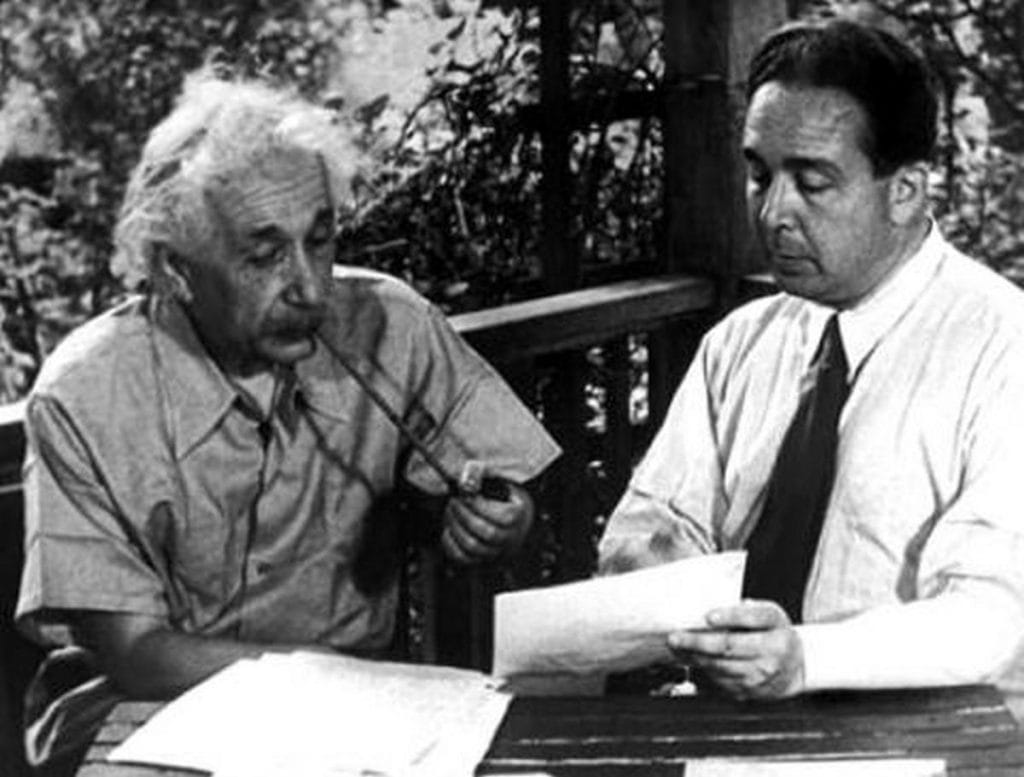

In 1945, Hungarian-German-American physicist Leo Szilárd (Máté Haumann) initiated the Szilárd petition, co-signed by 70 Manhattan Project scientists. The petition advocating for the US to forewarn Japan and to deploy the bomb in unpopulated islands.

Szilárd, the first to conceive nuclear chain reactions, drafted the letter for Einstein’s approval of the Manhattan Project. But despite his involvement, he became a vocal anti-nuclear warfare proponent.

Notably, he briefly resided in India during the 1930s while his wife worked with children. He interacted with many Indian scientists, including Obaid Siddiqui, founder-director of TIFR’s National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS).

One of the signatories of Szilárd’s petition was Lilli Hornig (Olivia Thirlby), who had originally joined as a typist at Los Alamos. Her scientific skills, however, proved prodigious. While she wanted to work with plutonium, there were concerns among the men that the radioactive element could be dangerous for the female reproductive system, as depicted in the movie. Hornig, therefore, worked with high-explosive lenses instead.

She later became a chemistry professor at Brown University and played a key role in establishing the Korea Institute for Science and Technology.

American nuclear physicist David Hill (Rami Malek) also signed the Szilard petition.

In the movie, he is shown giving a searing testimony in 1959 against U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) chairman Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) and his treatment of Oppenheimer— but more on that later.

Manhattan Project scientist Luis Walter Alvarez (Alex Wolff) also makes an appearance in the film. He is depicted as the scientist running out of a shop to tell Oppenheimer the news of German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann achieving nuclear fission.

Alvarez won the Nobel Prize in 1968 for his work in designing a liquid hydrogen bubble chamber which could take photographs of subatomic particles. However, his most enduring legacy is arguably the Alvarez Hypothesis, which he co-developed with his geologist son Walter Alvarez. The hypothesis states that the extinction of dinosaurs was caused by an asteroid impact.

Post-war tumult

After the Manhattan Project and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Oppenheimer grew disillusioned with atomic and hydrogen bombs.

He subsequently took over as the director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and later chaired the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission, while other nations pursued their own nuclear programmes, including India, where the Atomic Energy Commission of India was set up in 1948 under Bhabha’s leadership.

But Oppenheimer’s left-leaning communist ideals caused the US government to become suspicious of him as fear of USSR’s technological and military advances grew.

Adding to these suspicions was his on-and-off affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), a communist party member. The two intermittently shared a relationship both before and during his marriage with Kitty. Oppenheimer even named the 1945 Trinity test as a tribute to her, as she had introduced him to John Donne’s sonnet that said “Batter my heart, three-person’d God”.

The two last met in 1943 when Oppenheimer was already under FBI surveillance. And while Tatlock was found dead by suicide in 1944, at the age of 29, the affair had ripple effects even a decade later.

The pall of doubt over Oppenheimer’s ideological leanings led to a hearing by the AEC in 1954 that resulted in the revoking of his security clearance and effectively his role in the US atomic energy establishment. This initiative was backed by politician and then AEC chairman Lewis Strauss, depicted as Oppenheimer’s prime antagonist in the movie.

Upon hearing the news of Oppenheimer’s treatment, many in the scientific community were outraged and offered shelter to him in other countries.

Homi Bhabha was upset too. He was friends with both Robert and Kitty Oppenheimer and often dined with them when he was in New York. Bhabha went as far as to urge Prime Minister Nehru to invite Oppenheimer to immigrate to India after the 1954 hearing.

Oppenheimer, however, refused to leave the US, claiming it would not be inappropriate until he was cleared of all charges.

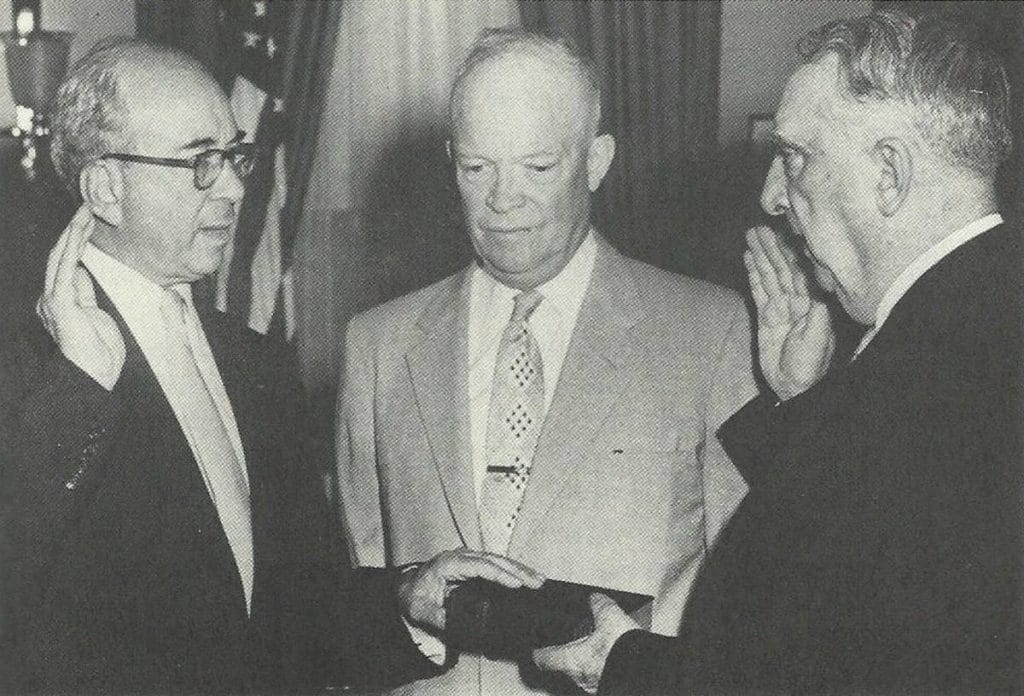

Significantly, the controversial hearing led to a backlash against Strauss too. In 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Strauss as Secretary of Commerce. But in the hearing to consider his nomination, depicted in black and white in the movie, many senators questioned his qualifications, specifically in the view of the Oppenheimer controversy. Strauss’s nomination was ultimately rejected by the Senate.

Epilogue

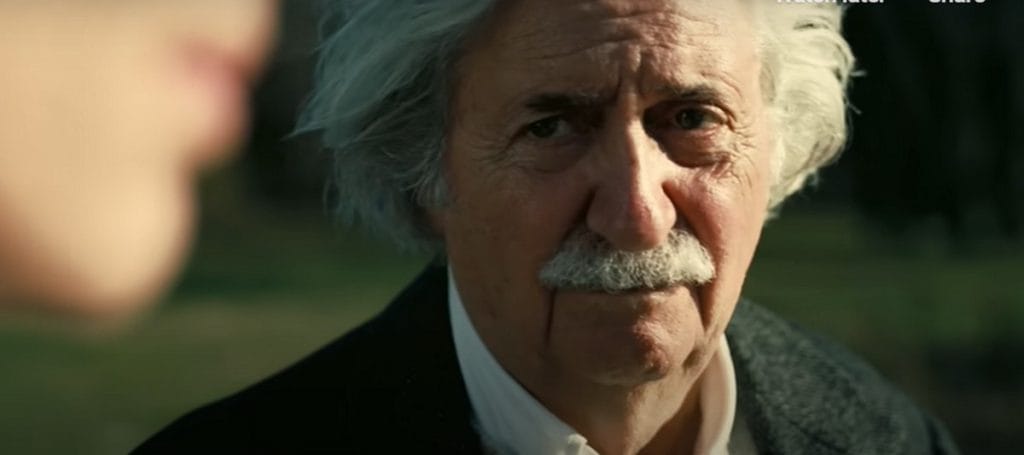

Oppenheimer’s time at Los Alamos and outside of it was full of legends of physics. The most well-known of these was, of course, Albert Einstein (Tom Conti).

A key scene in the film shows Oppenheimer seeking advice from Einstein about calculations suggesting that a nuclear explosion could destroy the earth.

However, as director Nolan has acknowledged in interviews, this interaction did not happen. Oppenheimer did seek similar advice, but he went to Arthur Compton, a Nobel Prize winner and director of Manhattan Project’s centre at the University of Chicago.

In real life, Einstein and Oppenheimer did become friends, but were closest when they worked together at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. It was here where Oppenheimer served the last years of his career, retiring in 1966. A year later, he died of throat cancer.

In December 2022, shortly after the release of the trailer of the biopic, the 1954 ruling to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance was nullified, citing a flawed process.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Oppenheimer joins the ranks of Wolf of Wall Street. A biopic that lionises the hero, no warts