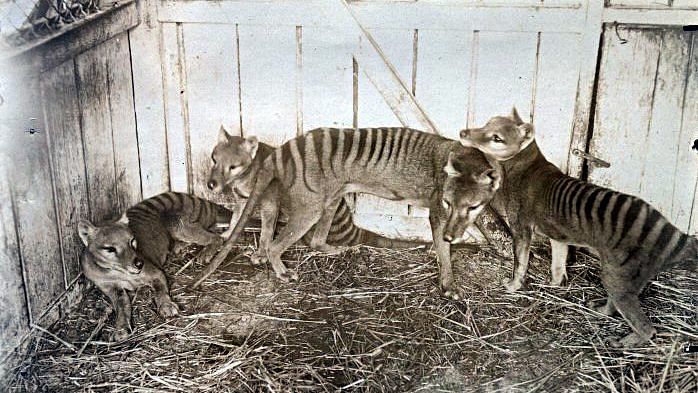

Bengaluru: The evasive Thylacine goes by many names in its native Tasmania, including the Tasmanian tiger and the Tasmanian wolf. The animal was native to mainland Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea; it was the largest known carnivorous marsupial.

The last member of its species was captured by humans in the 1930s and died in captivity in 1936; the species was thought to have gone extinct shortly after.

Along with the dodo and the passenger pigeon, it is considered to be one of the biggest symbols of human-induced extinction.

However, a new study documents thousands of verified and unverified sightings of the animal since 1910 up until the early 2000s, and concludes that the animal might have survived up until a couple of decades ago.

The study, currently under review, performed a detailed reconstruction and mapping of the spatio-temporal (space and time) distribution dynamics, and suggests that there is an unlikely chance the animal might persist in the wild today. The authors also conclude that such modelling is important to preserve other rare and unusual species currently on the verge of extinction.

History and extinction

Before Tasmania was colonised in the 1800s, the small island to the south of Australia was a secure habitat for the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus). The animal had already gone extinct in mainland Australia as a part of a larger wave of megafauna extinctions (dying of animals larger than 50kg) beginning about 10,000 to 5,000 years ago.

In the 19th century, the animal was hunted rampantly by fur traders and as a means to protect humans from their predatory nature. They were also threatened by the introduction of dogs to Tasmania, which both competed with their prey, like emus, as well as hunted the animal.

The last captive member of the species died in Australia’s Hobart Zoo on 7 September 1936, and the date is now commemorated annually as ‘Threatened Species Day’ in Australia. Fifty years later, in 1986, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) formally declared the thylacine extinct.

However, there have been many unconfirmed sightings since the 1930s in the Tasmanian wilderness, especially from former trappers, poachers and members of indigenous tribes. Some authorities too have reported sightings, and there have been many high profile searches for the animal over the past few decades.

Also read: Global ice melt accelerating at record rate, finds new study

Study findings

The researchers prepared a comprehensive database of sightings since 1910, traced their sources, geotagged them, confirmed their veracity and citations with support, obtained photographic and video evidence, and tallied all of them with government records to map the spatio-temporal distribution of the animal.

The result was 1,237 separate sightings, with 99 physical records of the animal and 429 observations made by experts. Of these, 271 actual sightings were made by experts who were professionally familiar with the animal, like former trappers, forest officials, scientists, and even bushmen. The animal was reported to have been sighted every year since 1910, except in 1921, 2008, and 2013.

The last unverified sighting was in 2019.

While mapping the sightings, the researchers were able to deduce a pattern of local losses through shrinking habitat, starting in places where agriculture and animal farming was widespread.

By the 1990s, the animal had shrunk in the wilderness as well, owing to human activity, dogs, and disease. The researchers state that the animal most likely became extinct in 1998.

Convergent evolution

The thylacine is a textbook example of what is known as convergent evolution.

In evolutionary biology, convergent evolution is the independent evolution of very similar physical features and traits in species that are separated by space or time.

The thylacine, which is endemic only to the Southern Hemisphere, eventually evolved to look like dogs or wolves that were not natively found in this part of the world. Dingos or native Australian dogs originally came to the continent from Asia with traders, and are thought to have been a driving force for the thylacine’s extinction. Thylacines were also similarly sized to dogs, and weighed between 20 to 30kg as adults, with an average length of 45 inches and a height of 20 inches.

The thylacine also evolved to have tiger-like stripes that radiated from the top of its back, which provided it with camouflage. The animal had soft fur, for which it was hunted. Its coat coloration had various shades of brown and its belly was white or cream coloured.

Both canids (wolf or dog-like animals) and tigers have placentas but the thylacine is a marsupial, which evolved to have an external pouch, like kangaroos and koalas. It also had a stiff tail like the kangaroo, which it was able to use to prop itself up on its hind legs.

But unlike kangaroos, the thylacine was a carnivorous marsupial, like the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii). It was the largest of its kind and was an apex predator. The animal was also able to open its extremely muscular jaws up to nearly 80 degrees for catching and carrying large prey.

However, while its genome is sequenced, its genetic history traced, and some inactive genes also activated in specimens, much is still unknown about this evasive and extinct animal, including the nature of its primary prey and hunting habits.

Researchers encourage the use of camera traps and other digital technology to scout for any remaining individuals of the species.

Such technology has worked in the past to identify live animals that were thought to be extinct, such as the Zanzibar leopard. The new study, yet to be peer-reviewed, is likely to provide useful assistance to both identifying any potential members left in the wild as well as protect other vulnerable species.

Also read: Dinosaur fossils found in Argentina could be of the largest animal ever lived on Earth