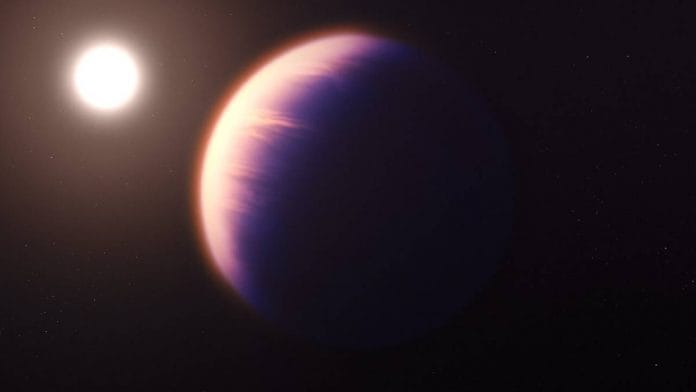

Bengaluru: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected the first definitive evidence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of an extra-solar planet. The alien planet outside our solar system is a gas giant that orbits a sun-like star 700 light years away in the Virgo constellation.

The planet, WASP-39b, has a mass equivalent to a quarter of Jupiter’s (or roughly the same as Saturn), and is 1.3 times the diameter of Jupiter. Its surface temperature is estimated to be 900 degrees Celsius and it orbits very close to its host star.

The planet completes its orbit in just four earth-days, at about one-eighth the distance from its star as Mercury is from the sun.

The planet was discovered in February 2011 by the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) project, and previously made news in 2018 when the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes discovered large quantities of water vapour in its atmosphere.

Carbon absorbs light at longer and more infrared wavelengths than water vapour does. Therefore, the JWST was able to detect carbon dioxide in its atmosphere when the Hubble and Spitzer couldn’t.

By knowing the proportion of carbon and oxygen present in WASP-39b’s atmosphere, scientists can obtain an understanding of the formation and evolution of the planet with relation to its star.

“Detecting such a clear signal of carbon dioxide on WASP-39b bodes well for the detection of atmospheres on smaller, terrestrial-sized planets,” said Natalie Batalha of the University of California at Santa Cruz, and team lead for Webb’s transiting exoplanet group, in a press release.

Also read: Exoplanet and its host star assigned to India set to get Sanskrit or Bengali names

Transiting exoplanets

WASP-39b was detected by the transit method, meaning that when viewed from earth, it can be seen passing in front of its star in its orbit. Such planets dim the light of the star they pass in front of ever so slightly, but enough for scientists on earth to be able to perform complicated calculations about the nature of the planet.

While some starlight is dimmed, some passes through the planet’s atmosphere as it passes in front of the star. The atmosphere filters out certain colours, depending on its composition. This can also be observed in our own skies that display fiery and colourful sunsets when there is particulate matter or increased pollution in the atmosphere.

Different gases absorb different combinations of colours across a spectrum of wavelengths, and this can be observed in the spectrum of the transmitted starlight from behind the exoplanet. By observing the missing colours, astronomers can deduce exactly the gases present in the atmosphere of a planet.

This method is known as transmission spectroscopy.

The spectrum of the planet itself is the most precise obtained for an exoplanet so far, showing large details and differences at a sensitivity never seen before, especially at the 3-5.5 micrometres range.

“As soon as the data appeared on my screen, the whopping carbon dioxide feature grabbed me,” said Zafar Rustamkulov, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University and member of the transiting exoplanet team. “It was a special moment, crossing an important threshold in exoplanet sciences.”

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also read: US team including 2 teenagers discovers ‘planetary lab’ with a rocky super-earth