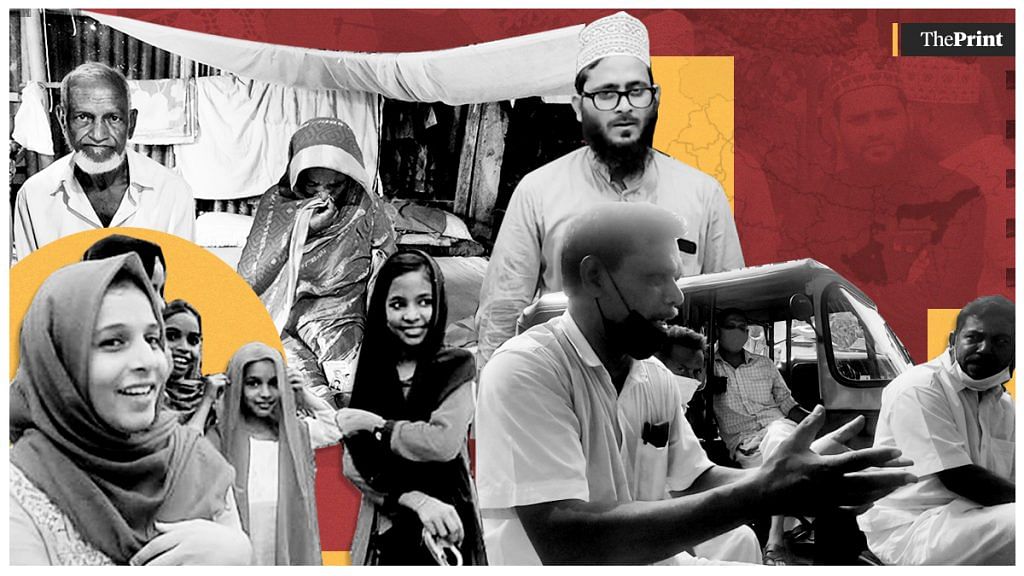

Fatima Khan, Senior Correspondent at ThePrint, travelled across various districts of the three key poll-bound states — Kerala, West Bengal and Assam — each with a large Muslim vote of 26, 30 and 34 per cent, respectively. But there are sharp political distinctions between the regions.

In Kerala, the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) has been integral to the Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF). West Bengal has a new dimension with the rise of fiery cleric Abbas Siddiqui’s Indian Secular Front (ISF) in challenge to Mamata Banerjee. And in Assam, Badruddin Ajmal’s All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) and the Congress, who have so far competed for the Muslim vote, have joined hands against the BJP.

Fatima found stirrings of change and political reassessments in all three states, especially among the young. While the three states have complexities, common themes across all remained the young Muslim’s desire for representation, abhorrence for being seen as any party’s captive vote, and a yearning for an unapologetic style of identity politics. Many older Muslims are uncomfortable with this and say they would still rather vote for the supposed ‘secular’ parties.

Read her detailed report:

Jahira Hossain’s father, a Haji, has a long beard, and her mother wears the hijab (head cover).

As Bengali Muslims, they have had their fair share of having to prove they are Indian, not Bangladeshi. But that one incident left a scar on Jahira’s mind, and reshaped her politics.

“We got into a long argument with the guard about why we are expected to prove we aren’t Bangladeshis. The humiliation has stayed with me,” said Jahira, who teaches literature at Kolkata’s Surendranath College.

Four years hence, Jahira, now 29, is set to support the newly-formed ISF floated by Furfura Sharif cleric Abbas Siddiqui, which hopes to win the votes of Bengali Muslims. Jahira is a voter in South 24 Parganas district’s Bhangar constituency, where Abbas’s brother Naushad Siddiqui is a candidate.

“As Bengali Muslims, we are used to being otherised every step of the way. Maybe that is what ISF will address — we might go from being otherised to finally being recognised.”

Also read: Didi or family? Furfura Sharif cleric’s family divided over whom to back in battle for Bengal

Najma Thabsheera and Abdul Nishad got married in February 2020 — barely a month before the Covid pandemic consumed the country. As young lawyers in Malappuram’s Tirurangadi region, both used their time during the lockdown to work towards a common cause — become more active IUML members.

Malappuram, a Muslim-majority district in Kerala, has always been the IUML’s stronghold. But while Nishad grew up in an IUML-supporting, politically charged family, Najma only began gravitating towards the party while at university.

“As a Muslim woman, you are not expected to talk about or be interested in politics. Even after all the education, I was told that my sole aim in life is to marry,” said Najma, 25. But while pursuing graduation in law at Calicut University, she came across Harita — the women’s wing of IUML’s student body Muslim Students Federation (MSF).

“Here, I met women actively talking about their aspirations, about being self-sufficient in every way possible. It was very inspiring,” Najma said.

While IUML has had women candidates in its municipal elections, this is the first time in 25 years that the party has fielded one for the assembly — Noorbina Rasheed in South Kozhikode. But Najma isn’t too bothered by that long gap.

“(The party is) getting there, bit by bit, working on various issues in society,” she said.

The IUML is the Indian successor to the pre-Partition Muslim League, and has been contesting elections for the last 70 years. It has had a minimum of two MPs in every Lok Sabha since 1962.

“The IUML has ensured that it echoes the grievances and demands of the Muslim community as a mainstream political party, without ever alienating any other community through its discourse,” said political analyst and writer-social commentator Shajahan Madampat, who is now based in the UAE but has lived in Kerala for most of his life and written extensively on the state and the IUML.

Madampat also made a distinction between a ‘communal’ party and a ‘communitarian’ party, putting the IUML under the latter umbrella.

“A communal party claims to represent sections of the society by projecting an enemy, whereas a communitarian party protects the interests of a community by being in the mainstream and not creating bad blood with any other community.”

Many commentators, in fact, cite an example from the past as proof of the IUML’s inclusive credentials — its senior leader, former Kerala education minister and now a three-time incumbent MP from Ponnani, E.T. Mohammed Basheer, launched the Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit in Kalady in 1994.

And yet, others point to the IUML’s descent from the Muslim League to attack it, such as when Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adityanath called it a “virus” last year.

“That’s the thing — just because the party has the term ‘Muslim’ in it, it will be seen a certain way. No one looks at how much IUML emphasises education and development,” said Nishad.

Also read: ‘They’re taking our girls to ISIS’: How Church is now driving ‘love jihad’ narrative in Kerala

But in all three states, their supporters state with full conviction that the parties shouldn’t just be identified with a single community — their aspiration is to be mainstream, that is to get votes from other parts of the electorate too.

“Bengali Muslims are in the majority among all the Muslims in the state. Urdu-speaking Muslims aren’t anywhere near the number of Bengali-speaking Muslims. So, why should we indulge in minority politics? We cannot afford to just because of the history of oppression. That would be reactionary,” said Abid Hossain, a 30-year-old documentary filmmaker who hails from Murshidabad, one of the two Muslim-majority districts in Bengal (Malda is the other).

Hossain refers to ISF founder Abbas Siddiqui as ‘bhaijaan’, as do several other supporters including young voters who have never met or interacted with the cleric but feel ‘seen’ by him.

This includes 27-year-old Sarah Ahmed, a queer person from Howrah who is now studying in Kolkata. She has felt discriminated against as a Bengali Muslim and been subject to slurs like ‘Go to Bangladesh’.

“Bengali Muslims are mostly from rural areas. But whenever we step outside, it is assumed we know Urdu. For the first time, we have a leader who speaks nothing but Bangla,” Sarah said. In fact, Abbas’s grandfather Abu Bakr Siddique is said to have begun the practice of giving the prayer khutbah or sermon in Bengali, to make it accessible to the masses.

Sarah isn’t quite sure where Abbas Siddiqui stands on issues of homosexuality, but is willing to give him a chance. “He is a cleric after all, so I am not sure what his view towards queer rights would be. But then, the ISF is part of the Left alliance which has shown commitment to LGBTQ+ rights, which is good,” she said, referring to the CPI(M)’s 2019 Lok Sabha manifesto.

Also read: ‘Mamata deceived Bengal Muslims’ — Furfura Sharif cleric launches party ahead of polls

Hamim Ahmed, an Assamese Muslim and lawyer in the Gauhati High Court took a sabbatical from his practice in 2014 to join the BJP.

“I am a five-time namaaz-offering Muslim, so my family and friends were surprised at my decision to join the BJP. I had this strong urge to do something for my community, to ensure welfare and development for Muslims,” Hamim told ThePrint.

Initially, he said, he got a lot of respect from the party, and was included in the state minority morcha and then made the chairman of the state Haj committee as well. However, gradually, he realised that the respect wasn’t due to his “Muslimness”, but more specifically the “Assamese Muslimness”.

“I came to the BJP as a Muslim, but I realised that the party’s emphasis is to court the votes of the indigenous Muslims alone, the ‘sons of the soil’. Then NRC came, and the undercurrent was entirely about us (local) versus those (‘foreigner’) Muslims, and I just began feeling very uncomfortable.”

Hamim quit the BJP in 2019 when he couldn’t live down the contradiction any longer. Today, he has become “apolitical” and has only one aim: To unite the Muslim community.

It a tough task due to the sheer size of the chasm, which Bengali-speaking Muslims are well aware of, especially since the NRC updation. ‘Miya’ is a common slur used for Bengali Muslims in Assam, but in 2016, members from the community turned the word on its head and began writing what is now known as ‘Miya poetry’, in their native dialects, describing the discrimination they are subject to.

In 2019, 10 ‘Miya poets’ got into trouble when an FIR was registered against them for depicting a “xenophobic” image of Assam in their poems.

Farhad Bhuyan, a resident of the Bengali Muslim-dominated Barpeta district, was one of the 10 poets named in the FIR, and told ThePrint why his work was important. “If we don’t talk about our struggles, who will? My poetry has only always talked about eliminating differences between the two identities (Assamese and Bengali),” he said.

Bhuyan whipped out his phone and recited his favourite, titled ‘Mandela is Coming’, which talks about young school girls under a tree reciting the ‘O Mur Apunar Desh’, the state song of Assam written by Lakshminath Bezbarua. Bhuyan has written the poem about his Miya identity, and the related oppression, but said he chose to write it in Assamese and not the Miya dialect to make it more accessible for everyone:

Jai gosor tole tole

Konmoina hotor

O mur apunar desh.

Also read: In Congress-AIUDF alliance, Assam’s Muslims see hope to keep vote intact, defeat BJP

This is because the ‘Muslim parties’ themselves were launched or gained momentum as an assertion against these ‘secular parties’, to not have their vote taken for granted anymore.

Political analyst and researcher Hilal Ahmed said Muslims have always been erroneously perceived to be a ‘bloc’, when that’s never been the case. “I have been tracking Muslim voting behaviour since 1962. Muslims aren’t a monolith,” said Ahmed, the associate professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS).

“Muslim voters aren’t just state-specific; they are also constituency-specific. At the constituency level, Muslims do vote by negotiating with various political parties as a survival strategy. But there is no such thing as a Muslim vote bank,” he added.

Trinamool chief and West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee has time and again been accused of ‘appeasement’ politics, and in 2019, she chose to counter that allegation by comparing the Muslim vote bank to a ‘cow to be milked’.

This did not go down too well with many Muslims. “If she’s calling us that, it just shows where we stand in the eyes of the party — as a captive vote,” said Sarah Ahmed.

The other allegation that always comes the way of ‘Muslim’ parties is that they serve to cut the anti-BJP vote — in Bengal, the ISF is likely to dent the TMC’s final tally. “But who is to say which party is cutting into whose votes? So many TMC MLAs have joined the BJP in the last few months. At least we won’t feel that kind of uncertainty while voting for the ISF,” said Jahira.

But things do get complicated when the AIUDF ties up with the Congress in Assam, because unlike the IUML in Kerala, Badruddin Ajmal’s party has opposed the national party since it was launched in 2006. Ajmal has been hugely popular among “insecure” Bengali Muslims, analysts say.

“The primary reason behind this alliance is to defeat the BJP. The Muslim middle class in Assam doesn’t want to be a captive voter of any party either, but then they know that if the BJP is to be defeated, this alliance is the only option,” said Sushanta Talukdar, senior political analyst based in Guwahati.

Senior BJP leader and Assam minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has repeatedly used the phrase “clash of civilisations” while referring to the AIUDF’s politics.

Talukdar said: “Phrases like these blur the lines between Assamese Muslims and Bengali-origin Muslims because they feel this sense of consolidating together against the BJP, and all other divides tend to get overshadowed by this.”

Also read: Behind BJP’s rise in Assam, a quiet RSS push that began before Modi, Shah & Sarma were born

Mohammed Sajjad, a 19-year-old literature student in Kozhikode, is strongly opposed to the IUML for this very reason. “The IUML does a lot of good work, especially for Malappuram. But outside a few pockets, it can’t make an impact in the long run. It starts many of its rallies from mosques; all decisions are made by the men in the party… It needs to be more flexible,” Sajjad said.

Benazir Ajmal, a 28-year-old Urdu-speaking Bihari-origin Muslim brought up in West Bengal’s Howrah, had similar views about the ISF, given that her family has no real connection with Abbas Siddiqui or the Furfura Sharif shrine. “Voting for the TMC is not a matter of choice. Muslims have to vote for the TMC to keep the BJP out. Moreover, if the ISF is headed by a cleric, it is bound to be conservative and orthodox. How much can I trust a religious cleric after all? It’s much better to vote for a tried and tested party,” Benazir said.

But it’s not just youngsters — several older Muslims across the three states, in their 50s and 60s, would much rather bank on the ‘secular parties’.

Basheer Sheikh, 51, is a transport worker in the UAE, but, being a committed Left Democratic Front supporter in Kerala for over two decades now, he returns home for a few weeks every election cycle to participate in campaigning.

“In Kerala, there is no need for a separate party for Muslims. We need a government that works for all people and the LDF is precisely that,” he said.

While a vast chunk of Muslims ThePrint spoke to say their experiences have forced them to be more invested in politics, a lot of poorer, more marginalised Muslims, have completely isolated themselves politically — mostly out of sheer disappointment.

Faizal Vyapari from Barpeta spent three years in a detention camp from 2016 to 2019, after being declared a ‘foreigner’ under the NRC in Assam. After getting bail, he returned home to find that three of his six sons had died. The family said all three died by suicide a year after Vyapari was taken to the detention camp.

“They were under great duress; their incomes took a hit, and the idea that their father might never be able to come out of the detention camp perhaps got too much for them,” said Vyapari’s wife Sabar Bano.

Faizal Vyapari used to make fishing nets for a living, and his family says it had to borrow and spend over Rs 5 lakh to travel back and forth from court hearings for bail in his three years in jail. Now, the family is in the grips of penury, and says it doesn’t have time for politics.

“We lost our three sons because of all this, how will we ever be at peace now?” the 70-year-old Vyapari asked.

Saddam Ahmed, a 31-year-old also from Barpeta, revealed that he was reeling under depression and anxiety.

“In the last three decades, every few years something comes up — either the D-voter (dubious voter) list, or then the NRC, or the detention camps… It’s exhausting and very depressing,” said Saddam Ahmed, who works as a contractual employee at a civil hospital.

But despite all this, Saddam Ahmed said he has not once considered moving out of Barpeta or Assam. “Politicians make life difficult, but the people here are largely good. There is a brotherhood that has sustained despite all odds, and that’s the only thing that makes life liveable,” he added.

(Edited by Shreyas Sharma)

Also read: Assam’s wave of ethnic anxieties now just an undercurrent. That’s what Modi-Shah achieved