New Delhi: When Nagaland got its first ever women MLAs this month — Hekani Jakhalu and Salhoutuonuo Kruse of the Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party — the jubilation overshadowed another milestone in a second northeastern state, Tripura.

The results of the Tripura assembly polls, announced on 2 March, showed that 15 per cent of the victors were women — the highest such proportion in any state assembly or Lok Sabha election over the past 25 years.

While the 15 per cent in itself — nine MLAs in a House of 60 — may not seem a significant number, it assumes importance in the context of women’s representation across legislatures.

ThePrint looked at Election Commission (EC) data for 150 assembly elections across states and six Lok Sabha elections (excluding by-elections for either assemblies or the Lok Sabha) held over the past 25 years, to analyse how women have been represented in different legislatures, and how this has changed.

Of a total of 21,161 MLAs elected in the past 25 years across all states and Union Territories (those re-elected are counted separately each time), only 1,584 were women, ThePrint’s analysis showed. This means that more than 92 per cent of all MLAs elected during this time were men.

The analysis also found that the average proportion of women elected in assembly polls between 1998 and 2023 has remained constant at 7-9 per cent.

When it comes to the Lok Sabha, women’s representation has seen a continuous rise over the past 25 years, from a mere 43 MPs in 1998 to 78 out of 543, or 14.4 per cent, in 2019.

Incidentally, Nagaland’s overall tally of women MLAs matches the number of women it has ever elected to Parliament — just two since 1963.

What factors could explain women’s poor representation, and what helps in improving it? ThePrint’s analysis found that possible indicators such as education and gender ratios, the size of the House, or even the presence of a woman leader at the top often fail to impact the outcome.

Sanjay Kumar, professor and co-director of Lokniti, a research programme at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), said, “There are some sections of voters who are not willing to vote for women candidates because they believe that if a woman gets elected, she won’t be as good a representative in a state assembly or Lok Sabha to represent their interests, but that is not the basic reason.”

According to Kumar, the Women’s Reservation Bill, which proposes to reserve one-third of all seats in the Lok Sabha and assemblies for women, would guarantee a minimum level of women’s participation in electoral politics. But 13 years after the bill was passed in the Rajya Sabha (March 2010), it is yet to be brought to the Lok Sabha.

Speaking to ThePrint, Fauzia Khan, a Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) Rajya Sabha MP from Maharashtra, said, “Women have always been at the forefront of service. Whether it’s any crisis, women are at the forefront (of fighting it). Sadly, the deep-seated historic, cultural, socio-economic barriers prevent women from taking their seat at the decision-making table so that resources and power are more equitably distributed.”

Khan added, “They (women) have always been at the lowest paid jobs and many in extremely vulnerable forms of employment. Many audits have shown that not more than six per cent of women have got a leadership role. So, we must think about it.”

Also read: Sonia, Mamata, Mayawati era receding. India is only grooming men as gen-next politicians

‘Parties don’t give poll tickets to many women’

Till Tripura’s milestone this month, it was Haryana (2014 election) and Chhattisgarh (2018) that had elected the highest proportion of women MLAs in the past 25 years. The figure was 14.4 per cent for both states.

This is particularly significant for Haryana, which as of the 2011 Census had the worst sex ratio (number of females per 1,000 males) among all Indian states, 879.

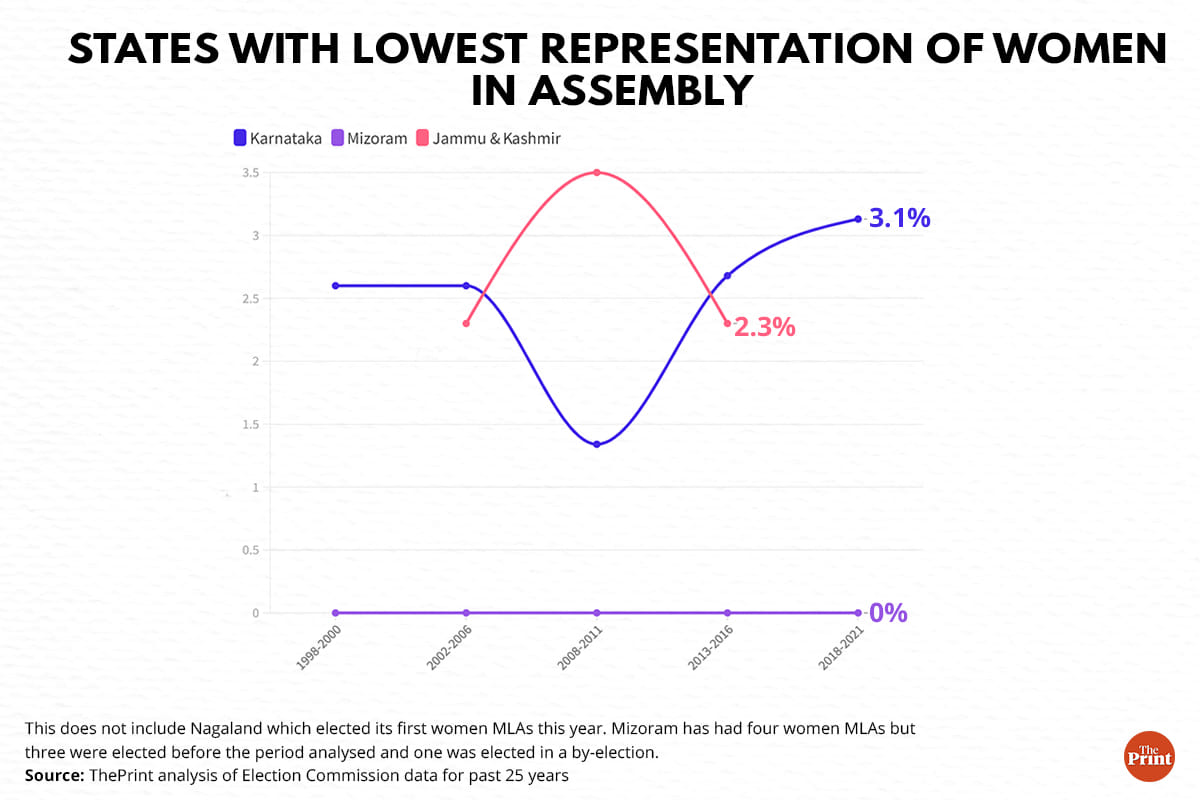

By comparison, Karnataka, set to go to polls this year, has been a consistent poor performer. The state’s best tally was in 2018, when it elected seven women MLAs in a House of 224 — just 3.12 per cent.

Some northeastern states fare worse. While Nagaland has just elected its first two women MLAs, Mizoram has only had four in its entire history. Three of them were elected before the 25-year-period analysed by ThePrint, and the other won her seat in a 2016 bypoll. The state’s last assembly election in 2018 resulted in an all-male House.

The percentage of women elected to the Jammu and Kashmir assembly (before the state’s bifurcation into the Union Territories of J&K and Ladakh in 2019) was also low — between 2.3 and 3.5 per cent — in the period analysed by ThePrint.

Experts, however, believe that the problem may not be that fewer women are being elected, but rather that fewer women are contesting elections.

“In India, votes are given based on political parties and parties do not give adequate tickets to women. If women contest as Independents, the winnability becomes very low,” said Kumar.

He added, “The basic reason parties don’t offer tickets to a large number of women candidates is that they think women will find it difficult to win elections. If parties don’t give tickets, women are not able to get elected to state assemblies and Lok Sabha. In some constituencies, women candidates also find it difficult to get elected because of the money and muscle power used by male members of their constituency.”

It is perhaps because of this that political analyst Rasheed Kidwai feels that, at least at the entry level, being connected to a political family helps women candidates.

“What concerns me the most is the fact that women workers are not able to come forward at the ground level,” Kidwai told ThePrint.

Literacy, sex ratio, women CMs fail to guarantee representation

There are no clear indicators of what helps in improving women’s representation in electoral politics.

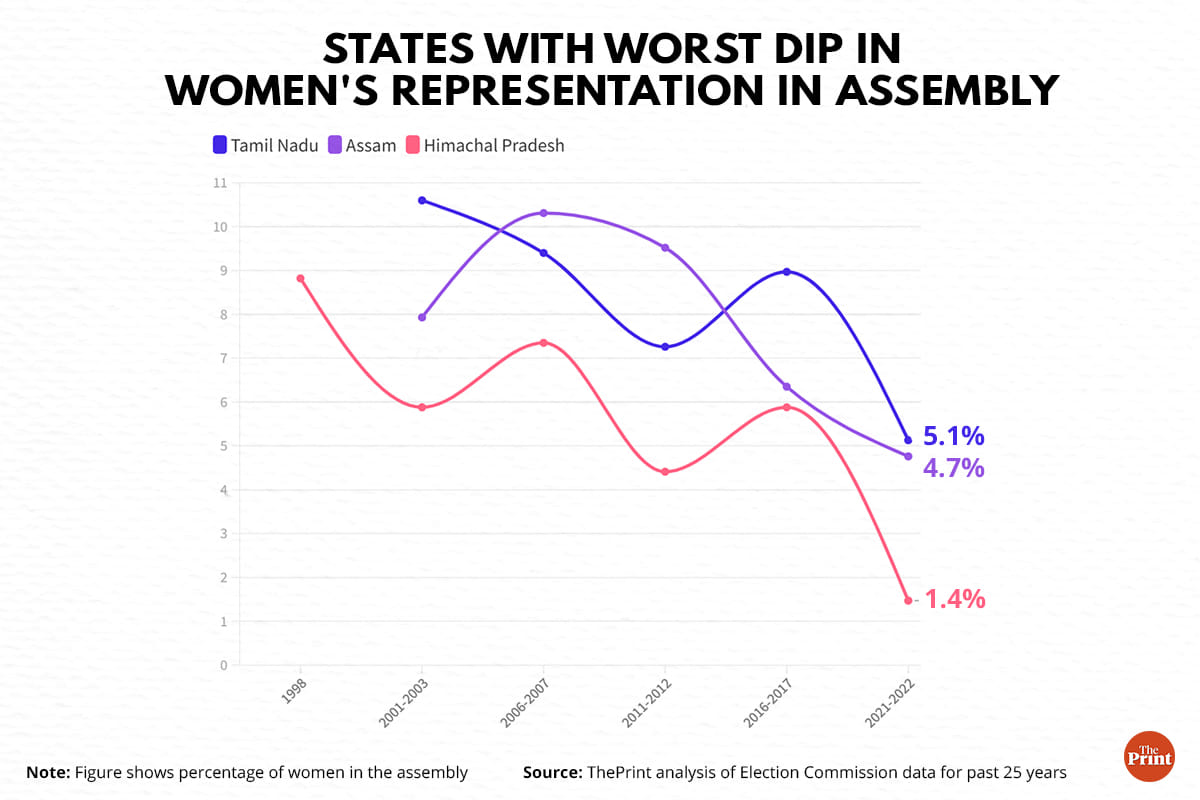

Take Assam, for example. In its past four elections, the proportion of women MLAs has gone down continuously from 10.3 per cent in 2006 to 4.7 per cent in 2021.

A research paper by three Assam-based scholars, titled ‘Political representation of women in legislative assembly elections of Assam’, was published in the journal WJARR last year. It cited several possible reasons for women’s limited presence in the state’s politics: a low literacy rate (66.27 per cent for women as of the 2011 Census), the burden of household chores, and low participation in the workforce (less than 40 per cent according to the paper).

But if literacy is a factor, the most literate state doesn’t paint a rosy picture either. Kerala — which had a 94 per cent overall literacy rate (92 per cent for women) as of the 2011 Census, as well as the highest sex ratio (1,084) — only has 11 women MLAs in a House of 140 (7.86 per cent).

Similarly, Mizoram, with just four women MLAs in its history, has the second highest women’s literacy rate at 89.27 per cent according to the 2011 Census.

Then, does having a woman chief minister help? States throw up mixed statistics.

In Tamil Nadu for example, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) sent its greatest number of women MLAs to the assembly between 1991, when J. Jayalalithaa became CM for the first time, and 2016, when she died. The 1996 election — won by a Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)-led front — was an exception.

In contrast, the 2021 election — the first one after Jayalalithaa’s death — saw the AIADMK send just three women MLAs to the assembly, whereas the victorious DMK sent six.

However, Delhi under Sheila Dixit, India’s longest-serving woman CM, shows a conflicting record. While the Union Territory elected nine women MLAs, its highest number in the past 25 years, in 1998 — the year Dixit became CM — the number dipped over her next two terms, dropping to just three in 2008. The Delhi assembly has a total of 70 members.

According to Kidwai, women at the helm do little to help their “fellow travellers”.

“Most of them (women CMs) keep the power structure in line with the patriarchal system. Women leaders have to act like men… More ruthlessly, no nonsense. They do very little to promote women’s representation,” he said.

Kidwai added, “Even in matriarchal societies like Kerala and the northeast, women’s representation is poor.”

Push for Women’s Reservation Bill

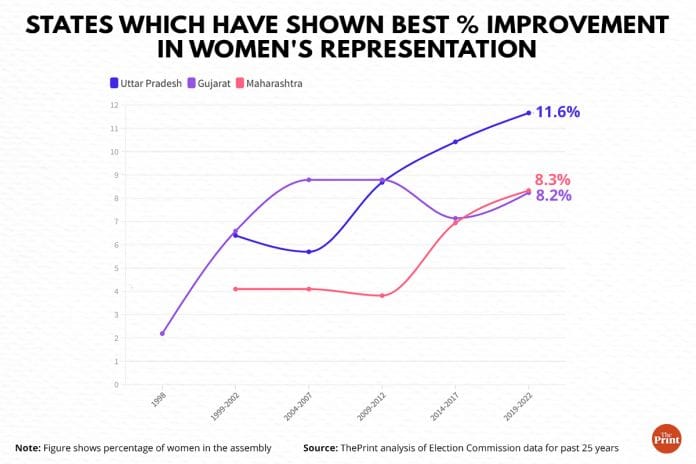

Among bigger states — those whose assemblies have more than 100 members — Uttar Pradesh has shown the most improvement in women’s representation in the assembly in a 20-year period. The state went from electing 26 women MLAs in 2002 to 47 in 2022, in a 403-member assembly. Maharashtra has shown the second-best improvement, from electing 12 women MLAs in 1999, to 24 in 2019, in a 288-member assembly.

Gujarat under former CM Narendra Modi also showed improvement, ThePrint’s analysis has shown.

The number of women MLAs in Gujarat went up from four in 1998 to 12 in 2002, Modi’s first election as CM. (He had already become CM in 2001 after being chosen by the BJP leadership to replace Keshubhai Patel.) Eight of the 12 women MLAs elected to the Gujarat assembly in 2002 were from the BJP. While Modi resigned as CM to become prime minister in 2014, the trend has continued: Gujarat elected 15 women to the 182-member assembly last year.

States that were created in the new millennium, meanwhile, throw up varying records.

After being carved out of Madhya Pradesh in 2000, Chhattisgarh elected an assembly comprising six per cent women MLAs in 2003. The same year, the Madhya Pradesh assembly had eight per cent women members. In the latest election in 2018, however, while Chhattisgarh elected 14.44 per cent women MLAs, the figure was only 9.13 per cent for Madhya Pradesh.

On the other hand, Telangana, carved out of Andhra Pradesh in 2014, has seen the percentage of women MLAs drop from 7.56 per cent to 5.04 per cent over the past two elections, in 2014 and 2018. Andhra, too, has seen a dip between 2014 and 2019, from 10.29 to 8 per cent.

One woman leader from Telangana, K. Kavitha — an MLC of the ruling Bharat Rashtra Samiti — has been trying to highlight the issue of women’s poor representation in legislatures. She sat on a day-long hunger strike at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar earlier this month demanding that the long-pending Women’s Reservation Bill be passed.

“If India needs to develop at par with other countries of the world, then women should be given more representation in politics,” Kavitha said.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: How women have come to hold the top post in 13 out of 45 countries in Europe