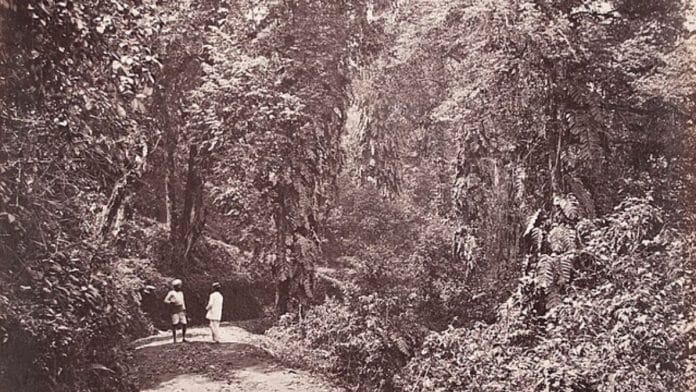

Up to the time of the Mughals, and well into the eighteenth century, India’s forest cover had remained pretty much intact. The great Terai belt of forest, running along the Indo-Nepal border extended from north Bihar to much of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Rohilkhand and past the Siwalik hills right up to the flood plains of the river Indus. Tavernier wrote of the region around Gorakhpur being ‘full of forests’ in the middle of the seventeenth century.

The southern parts of the plains of the Indus was largely scrub land or enclosed by the desert as it is even today. These extended from the Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Sindh up to Saurashtra. This area was home to the cheetahs, lions and wild asses and many of the imperial hunting grounds of the Mughals were located here.

The most extensive unbroken stretch of forest in Mughal times, much of which has survived to this day, was in Central India, extending from Orissa through Bastar, Bihar, southern Bundelkhand and Madhya Pradesh right up to Gujarat. Irfan Habib has termed this the ‘Great Central Indian Forest’. The forest belt extended down the Western Ghats to the tip of Kerala and covered most of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh along the beds of the Krishna-Tungabhadra and Godavari rivers. Large herds of elephants, tigers and all manner of game were found in the rich teak, sandalwood, rosewood and other exotic timber forests in these places.

Delhi lay at the foothills of the Aravalli range and was home to some of the most prized shikargahs under the Mughals. Its outlying areas—like Palam, Mehrauli, Najafgarh and Hauz Khas—were famous for their large antelope, leopard and tiger populations, while the extensive riverside khadar to the north and east was the natural habitat of a variety of game.

In the neighborhoods of Agra and Delhi, along the course of the Gemna, reaching to the mountains, and even on both sides of the road leading to Lahor, there is a large quantity of uncultivated land, covered either with copse wood or with grasses six feet high. All this land is guarded with utmost vigilance; and excepting partridges, quails, and hares, which the natives catch with nets, no person, be he who he may, is permitted to disturb the game, which is consequently very abundant.

Abu’l Fazl notes that elephants were found in large numbers in the provinces of Agra, parts of Berar, Allahabad, Malwa, Bihar, Bengal and Orissa.

Also read: 17th-century India was an Eldorado for the French—Taj Mahal, jewel mines, unimaginable wealth

The semi-arid regions of western and central India were the most fertile regions for hunting the cheetah. Pakpattan, Bhatinda, Bhatnair, Nagaur, Merta, Jhunjhunu, Dholpur and Hissar Firuza are all mentioned as shikargah-i muqarrars for providing great quantities of cheetahs.

In 1624, Jahangir used a lion hunt in Mathura as an opportunity to flush out farmers who had used the protection of thick jungles to indulge in acts of defiance by refusing to pay taxes to the jagirdars and to commit highway robbery. Bari in Dholpur was a famous shikargah where Jehangir was attacked by a lion and only saved by the valiant intervention of Anup Rai and Prince Khurram, the future Shah Jehan. Jehangir also refers admiringly to the Empress Nur Jehan shooting tiger in the vicinity of Mathura.

The forests surrounding the water bodies around Hissar and Karnal also had a great concentration of game for the chase, such as antelopes and nilgais, and were particularly famous as cheetah terrain, an animal that could be trained to hunt alongside the emperor. The thick forests along the river Brahmaputra in Assam, and more generally in the Northeast, were home to all manner of game, especially wild elephants, rhinoceros, tiger and deer, which remained virtually untouched till the arrival of the British who started to exploit the timber commercially and started planting tea gardens in the foothills.

The Mughal penchant for cutting vast swathes of forests that hindered the movement of troops and their love of hunting resulted in the absolute decimation of wildlife in different parts of the subcontinent. Many rich breeding grounds of elephants were destroyed; the great Indian one-horned rhinoceros disappeared from the Indus Valley; the cheetah teetered on the brink of extinction and the majestic lion became confined to the western extremities of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Saurashtra.

This was to prove the afterglow of the day; the sunset was fast approaching.

When the British first established their hold on India, first in Bengal, Carnatic and then slowly over the rest of the country, they were confronted by the country’s vast forests and, for them, its terrifying beasts—tigers, elephants, snakes, wild buffaloes and lions, which seemed to be the carrier of dreaded diseases like malaria, typhoid and cholera.

The gloom of the forests had to be cleared, in part because timber was required for building ships and wooden ties for railway lines, but also because land was needed for growing commercial crops like cotton, tea, coffee, cardamom, rubber, spices and opium. Animals that destroyed these crops would necessarily have to be culled, so hunting acquired a new prestige. Sporting and hunting were an ancient tradition linked to the aristocracy in England. This was now carried to India as a marker of identity separating the colonizer from the colonized.

Generations of young British recruits inducted into India were brought up on the idea that hunting was a gentleman’s sport and that India’s forests were a sportsman’s paradise that provided unlimited opportunities to pursue and kill wild animals. Hunting was a sign of being seen as a pukkasahib, and the ability to hunt became a distinguishing mark of aristocratic privilege that attended the right to rule.

Hunting was also presented as a way of protecting the ‘natives’ from the ravages of ‘savage beasts’. Animals were thus termed as vermin and game that had to be exterminated in order to preserve peace in the countryside. Rewards were announced for destruction of carnivores which included rewards for killing tigers (Rs 7), leopards (Rs 5) and others such as bear, hyena and wolf (Rs 3).

The ninety years between the establishment of Crown rule in India post the Great Uprising of 1857 and India’s Independence in 1947 saw a marked change in the forest cover of the country and its wildlife population. Gone forever were the great herds of wild elephants in the dwindling forests of the Sundarbans, Nilgiris and Central Indian plains. Gone too were all signs of the rhinoceros from North India, who were now confined to the Brahmaputra basin in Assam. Lions were now extinct in all parts of the country except Gujarat and the feline grace of the cheetah would forever be lost to the subcontinent.

According to Mahesh Rangarajan, over 80,000 tigers, more than 150,000 leopards and 200,000 wolves were slaughtered in the fifty years between 1875 and 1925.

Following on the heels of the British were the maharajas and princes of the erstwhile semi-independent princely states. They reserved the right to hunt in their territories. However, stories abound of their organizing, with pomp and splendour, elaborate hunts for their colonial masters. Kings and queens, archdukes, presidents and viceroys, political and district officers were often royal invitees.

As Mahesh Rangarajan has remarked, ‘In the annals of the hunt, the Indian princes stand out in a league of their own. Despite recent attempts to rewrite their role as precursors of modern-day conservation, their record was not always an edifying one.’

This excerpt from An Officer and a Tiger by Yogesh Chandra has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from An Officer and a Tiger by Yogesh Chandra has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.