Foreknowing that the matter would end in their favour, Hindu orthodoxy, financed by the ever-calculating shetyas, did away with the expensive Macpherson this time. The old duo of Vicaji and Mankar were good enough for the consul’s nominal role in the farce.

Latham being away in England, Rukhmabai was represented by Inverarity and Telang. Realizing that there was little they could do to alter the course pre-set by the appellate court, Rukhmabai and her consul did not even care to object to the case being tried by Farran who, as a lawyer before his elevation to the Bench, had drafted Dadaji’s original plaint. They had no use for technical trivia. Their gaze was fixed elsewhere. After the requisite procedural steps had been gone through before the Bombay High Court, they would take the case to the Privy Council in London. Latham had even made their intention known to the appellate court. Meanwhile, they would maintain a high moral ground which was likely to improve their chances before the Privy Council.

The farce opened with usual solemnity in Farran’s court. Vicaji, speaking for Dadaji, recapitulated the facts of the case. The judge then called upon the defence for its evidence. To that Inverarity responded by demonstrating the futility of the exercise. He could, he submitted, produce evidence to corroborate Rukhmabai’s contention that she had not consented to the marriage into which she was being dragged. But the appellate court had already invalidated that. He could also prove that Dadaji, who claimed her company, was unhealthy and too poor to maintain her. But that had been ‘practically admitted’ in the testimony of Dadaji himself and his witnesses in the court of Justice Pinhey.

Rather than attempt any exercise in futility, Inverarity concluded his brief spirited presentation by saying that he would ‘content himself with protesting against the decree which the court would no doubt consider it proper to make’.

Also read: How Ram Guha’s editor helped him capture rise and fall of India’s bilingual intellectuals

Their Lordships – Sargent and Bayley – had in their farce assigned Rukhmabai the role of a foredoomed silent victim. She, instead, came up with an utterly novel form of resistance and frustrated the entire plot. With due deference to the court, she declared that she would not obey its order to go to Dadaji. She would rather submit herself to the maximum penalty admissible under the law: six months’ imprisonment and/or forfeiture of property.

She, who dreaded to go to a court of law, was ready to brave six months in jail. She, who would need to fend for herself as a single woman, was ready to forego all her property.

She would not go to that man.

The ‘enslaved daughter’ – Rukhmabai’s collective self-description for India’s womanhood – had had an epiphany. No power could keep a free soul in bondage. She would be a free soul. She had glimpsed the power of moral resistance. Anticipating the power of satyagraha before satyagraha was known, she had turned a notoriously no-win situation into a triumph.

That was 1887. Here is a contrast to appreciate Rukhmabai’s action. Four years prior to this, Surendranath Banerjea, the fiery male nationalist, was hauled up for contempt of court for writing a spirited article in his weekly, the Bengalee. Advised by W. C. Bonnerjee, the eminent lawyer who would two years later become the first president of the Indian National Congress, Surendranath tendered an apology forthwith. The apology, ironically, could not save him from going to jail.

Farran had no option but to complete the farce scripted by the appellate court. Saying that the case was for institution or restitution of conjugal rights, he ordered Rukhmabai to ‘go or return’ to Dadaji’s house within a month, and inform the court of compliance with the decree.

The judge and the rival consul were, or pretended to be, untouched by the grandeur of Rukhmabai’s defiance. So at least their immediate conduct showed. They seemed to want her to be taught a lesson for her intransigence. So, when Inverarity asked Farran to reverse his decision about costs, the peeved judge remarked that had Rukhmabai ‘expressed her intention of obeying the decree’, he would have made Dadaji pay. Similarly, Dadaji’s consul refused even the request for advance notice of the despatch of the bailiff to Rukhmabai’s house.

The effect in the world outside was electrifying. Rukhmabai’s sworn opponents – the leaders of Hindu orthodoxy – were the first to sense the power of her defiance. They were jubilant, and relieved, that they had, in a mere year and a half, got rid of Pinhey’s dangerous verdict. But this was not the triumph they had planned. They had meant to crush Rukhmabai in a way that would serve as a deterrent to future Rukhmabais. That had not happened.

Shrewd men of the world, they sensed that the young rebel had brilliantly outmanoeuvred them. Any attempt to execute the court’s decree would give her just the chance she wanted. She would court the requisite punishment, emerge as a martyr and make Hindu culture a laughing stock in the entire civilized world.

Even if Rukhmabai chose not to court punishment and appealed against Farran’s decree, Hindu orthodoxy would gain nothing. The reversal of Pinhey’s judgment had done what they needed. Hindu law had remained unscathed. Further litigation could culminate in an appeal to the Privy Council, which might restore Pinhey’s ruling. The orthodox were most keen to avert that danger.

They were keen to make the decree a dead letter. They had used Dadaji as a pawn to serve their cause and brought him tantalizingly close to getting hold of his wife. Now the cause required them to sacrifice the pawn.

The orthodox, shrewd men of the world would not, of course, admit to having been frightened by the young woman. Forced to try and forestall any more litigation, they provided a new fillip to Rukhmabai’s character assassination which had begun after Pinhey’s verdict. Besides compensating for their supine surrender, that would help create the illusion that the reason for not enforcing the decree was that no respectable man would deign to live with a ‘loose’ woman like Rukhmabai.

Rukhmabai’s story resonates with the struggles of many women in colonial India, including figures like Rukmini Devi Arundale, who also defied societal norms. Her journey in the world of Bharatanatyam and her refusal to conform to expectations highlight the broader fight for women’s rights during this tumultuous period.

The lead in fanning this pathological fury against Rukhmabai was all along taken by Tilak’s powerful weeklies, the Kesari and the Mahratta. Within three weeks of Pinhey’s judgment, on 13 October 1885, the Kesari had pruriently alleged that the judge and the lady were ekaroopa, one and the same. After Rukhmabai’s defiance in Farran’s court, the weekly became more vile and vulgar. On 29 March 1887, in a burlesque entitled ‘The Final Scene in the Rukhmabai Farce’, it portrayed Rukhmabai as a self-indulgent, licentious woman who would rather go to jail than to her lawfully wedded husband. Was such a woman worth living with?

A close second was Dr Kirtikar, the irrepressible England-returned surgeon and self-professed social reformer. Speaking, of all places, at the Bombay Prarthana Samaj, and claiming first-hand knowledge, Kirtikar detailed Rukhmabai’s ‘roving sensational life’. Denying that she was a champion of women’s emancipation, he said:

Rukhmbai is dependent on her well-wishers. Where is her independence? … Does it constitute a state of freedom to secure the opportunity of living in association with educated European friends instead of an uneducated husband?

Kirtikar topped his innuendo with the question: ‘What will happen to her after another ten years?’

In distant Bengal, its most esteemed weekly, the Hindoo Patriot, called Rukhmabai a ‘golden lady’ and ‘Girl of the period’, and conjured up a titillating description of her daily routine:

… an accomplished young lady who can sing and dance and playon the piano, and whose proper sphere is the ballroom at night, and the Apollo Bunder or the Bandstand at time of the setting sun …

Facts, when it came to Rukhmabai, succumbed to febrile imagination even in the case of these otherwise educated, cultured and honourable men. Everyone knew that Rukhmabai, unlike Dadaji, could not marry again. That, in Malabari’s unforgettable phrase, she could not escape the ‘brutal embrace’ of her nominal husband.

Yet, condemning her as a woman who had been led astray by her beauty and corrupted by Western lifestyle, Prachar, an otherwise respectable Bengali monthly, confidently predicted that she would pick a new husband from among the many vilayati and ‘native’ sahebs she had befriended.

Their hearts bleeding for Dadaji, those sadist men chorused in unison: a licentious woman like Rukhmabai was not worth living with. Some even addressed Dadaji directly, like Kirtikar, who advised him to bid Rukhmabai ‘a distant good-bye’.

Hindu orthodoxy was unhinged by Rukhmabai.

Even the stolid colonial dispensation was completely taken aback by her defiance. Discreet enquiries confirming that the young lady was ‘determined not to obey’ the decree, the Bombay government hurried to request the Government of India to forestall the impending crisis.

The Viceroy, to whom the request was addressed, was himself no less rattled. The same day as the Bombay government despatched its request, the Viceroy sent the following telegram to his Law Member:

‘I hope you are keeping your eye on the Rukhmabai case. It will never do to allow her to be put into prison.’

Burdened with their civilizing mission, the white rulers did not wish to be seen – in India, in their own country and in the wider world – as sending a woman to prison for daring to follow her conscience.

Dufferin understood something else, too, which shows how well he appreciated the real power of Rukhmabai’s defiance and the dynamics of its operation. Months after his telegram to his Law Member, he wrote: ‘It would be a good thing for the cause if Mrs or Miss (?) Rukhmabai were sent to prison; but still we must prevent it somehow.’

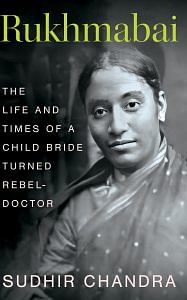

This excerpt has been taken from Sudhir Chandra’s ‘Rukhmabai: The Life and Times of a Child Bride Turned Rebel-Doctor’ with permission from Pan Macmillan India.

This excerpt has been taken from Sudhir Chandra’s ‘Rukhmabai: The Life and Times of a Child Bride Turned Rebel-Doctor’ with permission from Pan Macmillan India.