On the evening of 14 April 1986, just after American F-111 bombers struck targets across Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, President Ronald Reagan invoked the lesson of Munich 1938. In justifying the raid, undertaken in retaliation for a West Berlin discotheque bombing ten days earlier, the president said that ‘Europeans who remember history understand better than most that there is no security, no safety, in the appeasement of evil’.

He was not alone in conjuring up the ghost of Munich. In defence of Neville Chamberlain, some historians have argued that the Munich Pact allowed Britain time to prepare adequately for war. Fredrik Logevall and Kenneth Osgood, for example, contend that ‘for Chamberlain, Munich indeed represented a tactical victory of sorts. It provided England with a breathing spell to build its strength in preparation for the likely showdown with the Nazi juggernaut.’

In a similar vein, some have suggested that in the present time the collective West – including the United States, NATO and the non-NATO allies – could defeat Russia in a direct conflict, given the imbalance in population size, economic strength, technological prowess, commercial sophistication and military budgets, all of which favour the West. But this assumes a unified West that could agree on the nature and seriousness of the threat, succeed in mobilising and coordinating its efforts, and accept the real risk of a thermonuclear conflict against a great power.

All of this seems very doubtful given the current state of affairs. Moreover, as noted earlier, while Ukraine’s motivation in its fight for survival outweighs Russia’s fight for a more favourable regional security architecture, Russia’s motivation in turn outweighs that of many Western allies. Thus, while the conflict in Ukraine seems in some ways like a ‘Munich moment’, it may prove necessary for Western leaders – as it was for Chamberlain – to play for time lest, in attempting to re-establish deterrence, they instead suffer a major defeat that would destroy it.

By the start of 2024, it had become clear that the military power of Ukraine, augmented by erratic and often delayed Western supplies of money and materiel, could not defeat Russia or force it out of Ukrainian territories.

Instead, for Ukraine to stave off defeat and remain an independent sovereign state, both Ukraine’s Western backers and its civilian and military leaders in Kyiv needed a fresh approach which upped military and other forms of assistance in a manner that could off set Russia’s improving battlefield prowess, its inherent numerical advantages and its growing defence industrial sector strength (with Chinese help), and could defeat a leader in Vladimir Putin who had wagered his presidency on victory. And they would have to do so in a way that did not require an open-ended financial commitment to Kyiv, which the politics of the West is unlikely to permit.

While it might have been desirable, at some point in the past, for the West to draw a red line for Moscow, signalling the limits of acceptable Russian territorial expansion (such as by establishing a clear trigger to automatically include Ukraine in NATO) and thus threatening direct conflict beyond a certain point of advance, this option got caught up in Western political ambivalence. President Biden’s weak formulation immediately prior to the invasion – that if Russia mounted anything more than a minor incursion, there would have to be a ‘discussion about consequences’ – hardly suggests a willingness to accept such risks.

Also read: Losing OCI was an intimate shame at first. It freed me later: Aatish Taseer

If Ukraine loses the war – that is, if Russia once more exercises control over Ukraine’s political, economic and social life, even in the absence of physical occupation of Ukrainian territory – the long-term, strategic implications for the democratic world would be both profound and negative. Ukraine under those circumstances would become a ‘non independent state’, like the Republic of Karelia inside the Russian Federation, or a Russian dominated neighbour like Belarus, or, at best, it would be subject to Russian control of its foreign, defence and internal policy. The current leadership of Ukraine would be killed, jailed or forced into exile.

In so doing, they and ‘NATO’ (as the proxy for the West) would be blamed for the war, and the United States and its allies would see a further catastrophic degradation of their deterrent capability, thereby encouraging adventurism among every adversary on the planet. Moscow, for its part, would probably seek to install a puppet president heading a government made up of Ukrainians loyal to Russia. Ukraine’s independent media would be silenced, with no political opposition permitted.

A systematic campaign against pro-independence Ukrainians would ensue, almost certainly leading to a civil war within unoccupied areas of Ukraine, and a guerrilla resistance war against Russia in areas occupied by Russian troops. Ukraine’s economy would again be dependent on Russia, with Ukraine and Russia together dominating the global export of grain, weaponising the commodity with severe implications for import-dependent economies.

Inside Russia, instead of Putin having to deal with the impact of a Russian defeat in Ukraine, Russian society would take a further step towards authoritarianism. Buoyed by success in Ukraine, Russia would continue its war preparations and transformation into a war economy, Soviet-style.

The next target for Russian influence, in the assessment of the Finnish regionalist Kari Liuhto, would likely be Moldova (Transnistria), followed by the Caucasus (Armenia and Georgia), and thereafter the Balkans. It would not necessarily stop with Putin. In this environment, any successor would very likely need a regional conflict, if not an open war, to strengthen his image among the Russian siloviki (literally, strongmen).

The European Union would have to prepare for millions of new war refugees from Ukraine. EU countries would need to increase military budgets, diverting resources away from other areas, an effect potentially worsened by floods of Sahelian refugees encouraged by Russian actions in Africa. EU unity is already weakening as some seek accommodation (and profit) with a resurgent Russia; it would only weaken further in the event of a defeat, as the search for European culpability for the ‘loss’ of Ukraine began. Such stresses would be intensified by the loss of US deterrence, which would be likely to result in a crumbling of the transatlantic relationship as the era of extended US deterrence in respect of European security ended.

Elsewhere, Beijing’s intimidation of Taiwan would take a step forward as Xi Jinping took account of the absence of any effective US deterrent. The chance of an invasion of Taiwan – or of the island perhaps falling without a fight – would allow Xi to make his name in history by reuniting Taiwan with mainland China, thereby risking the first of the ‘chip wars’.

More generally, Ukraine’s loss and Russia’s victory would strengthen and unite authoritarians worldwide at the expense of democrats, increasing the likelihood of regional conflicts as Western powers, discredited by yet another defeat, lost their ability to deter. The United Nations would fragment further, and regional alignments such as BRICS would grow in influence.

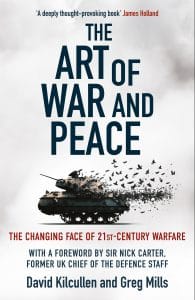

This excerpt from ‘The Art of War and Peace: The Changing Face of 21st Century Warfare’ by David Kilcullen and Greg Mills has been published with permission from Bonnier Books UK.

This excerpt from ‘The Art of War and Peace: The Changing Face of 21st Century Warfare’ by David Kilcullen and Greg Mills has been published with permission from Bonnier Books UK.