I was once travelling solo in a cab in Varanasi. The cab driver who found it necessary to declare to me that he was a proud Yadav, a descendant of Krishna, asked me matter-of-factly—aapki shaadi hui hai? (are you married?) I said no. Hamaare yahaan bina shaadi ke, ladkiyaan aise akeli baahar nahin aati (here unmarried women do not come out alone like this). Essentially, he was saying, women ‘are not allowed’ to come out alone.

Later in the day, I was in another cab, where the driver again asked me the same question. Since I was smarter now, or so I thought—I said, ‘yes, I am married’ with great confidence. Quickly he said, in this region married women only come out with their husbands. Not alone like this.

Doomed this way. Doomed that way.

What happens in Carnatic music, especially with women percussionists, is not very different. Not wearing a saree may be an issue. But that doesn’t mean wearing a saree makes the path a bed of roses.

In 1933, E. Krishna Iyer, an eminent lawyer and freedom fighter, recorded an incident in his book Personalities in Present Day Music. The incident is about C. Saraswati Bai, an exponent of kathakalakshepam (a form of religious or musical discourse combining storytelling, song, poetry). ‘When she first attempted to appear in public,’ says Krishna Iyer, ‘she had to meet the prejudices and opposition of most of the male musicians.’ Once a performance of hers had been arranged by a music sabha in George Town in Madras. On the day of the performance, however, it had to be cancelled since the professional male musicians had threatened to boycott the sabha if they went ahead with her performance. Kathakalakshepam at that time was dominated by men and Saraswati Bai’s foray into this genre was seen as a threat by them. Her performance was later organised by another patron at his residence in Mylapore.

The year was 1974. Sukanya was about seventeen when the family of Kothamangalam Subbu, the famous Tamil poet, writer and filmmaker had organised a harikatha (similar to a kathakalakshepam) performance in his memory. Singer and composer K.C. Tyagarajan was performing the harikatha that day and he had taken young Sukanya along to play the mridangam for him. The men in the gathering were visibly unsettled to see a girl in a pavadai (long skirt) enter. One of them called Tyagarajan aside and said, ‘We do not want women to perform here. Could you send her back and get a male accompanist?’

Essentialising of the woman’s body in Carnatic music, therefore, has a long history that is complex and layered. Almost everything about the woman is codified—how she must dress, how she must move, how she must think, speak or act. Women who sing or play melodic instruments such as the veena or violin, often ‘perform’ (also, are expected to perform) this ‘image’ of the quintessential woman. However, when it comes to percussion-playing, the woman’s body is slightly a misfit in that it does not fully comply with prescribed conventions. As Carnatic vocalist, author and activist T.M. Krishna writes in his book A Southern Music: The Karnatik Story, ‘women were supposed to personify the feminine side of music; therefore, their music was all about elegance, beauty and tenderness.’ In relation to these set standards, a woman’s body playing percussion sits and moves in a manner that makes it ‘un-feminine’. Such a body challenges established ideas and stereotypes and asks questions—precisely what the system disallows women to do.

In music, as in other areas of life, experiences of rejection and effacement are not uncommon to women. If there is one point that Sukanya ji and I argue about and many a time disagree with each other, it is on the question of how we respond to the various shades of everyday misogyny. Our approaches are different. I have to admit that my threshold of tolerance is quite low. She, on the other hand, has astounding levels of patience.

A senior music scholar told me some years ago, that a celebrated mridangam player, needless to say, a man, had once said to him, ‘If there are sarees on stage, who will look at me?’

However, to think that blatant misogyny is a thing of the past, is to be thoroughly mistaken. One such incident happened as recently as ‘just before Covid’. Sukanya ji was scheduled to play at an important music festival in Bangalore. That morning, she called me saying that the secretary of the sabha had called to ‘inform’ her that the esteemed mridangam player for the day, a senior man, had declined to play with her and so she need not make the effort to come that evening. This particular senior mridangam player had in fact played with her in the past, but now, apparently, he had decided to no longer play with women!

Many male musicians today who refuse to perform with women consider it a matter of great pride, even some sort of ‘inner spiritual evolution’. They are invariably camouflaging their misogyny with the most unreasonable logic. This is true of the said mridangam player too.

Also read: ‘Don’t call me Boomer.’ On being young, young-old, and old-old

I was livid when I heard this. Sukanya ji was calm. I was even more livid because she was calm. That concert organisers even had the gumption to dismiss her rather than dismiss the mridangam artist was something I could not fathom.

Following this, I happened to share my disquiet with a peer mridangam player, a young man. He simply justified the senior mridangam player’s stance. ‘There is a reason why seniors take such decisions. You must not question. And you are too young (in the field as a percussion player) to understand all this,’ is all he had to say.

In patriarchal systems, ‘whatever is’ must be accepted as natural. It calls for ‘uncritical acceptance’. Experiences of rejection that women have in all phases of learning, practicing and performing the art they love so dearly, are considered, to quote the American art historian Linda Nochlin, but ‘minor, peripheral, and laughably provincial sub-issues.’

It is within this matrix that I must then ask the critical question that Linda asks in her groundbreaking essay written in 1971, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In this context, ‘why have there been no great women percussionists in Carnatic music?’

In my early years as a student of the percussion, this was an existential question for me. As a woman playing percussion, I wanted to know my lineage. If temple sculptures, miniature paintings and murals across India are documents we can go by, then we know that women have routinely played percussion since medieval times. By this time then, history should have supplied us with scores of names of women percussionists. But as we know, it hasn’t. Or at least it is not immediately visible. The lamps of documented history only illuminate select areas. On the other side is the shadow. Unknown to us, are the vast umbra-penumbra regions where exist voices that for long have been silenced, suppressed, marginalised and invisibilised. Nonetheless, many of these continue to survive, speak and subvert—if not like perennially flowing gurgling streams, at least as quietly trickling rivulets. We will find them only if we care to see patiently; if we care to listen attentively.

In any case, history can sometimes be shrewd. When posed with difficult questions like this, from a long list spanning decades or even centuries of artists, who are supposed to have created history with their artistic excellence it pulls out names of a few women—one here, one there, as tokens, so that the question can be put to rest. Therefore, when the question ‘why have there been no great women percussionists in Carnatic music?’ comes up, the answer will always be ‘oh! but there are women’—pointing to the few that we know from recorded history.

The only two percussion playing women, both seniors to my guru, whose names I had known before I started my search were N.S. Rajam and Dandamudi Sumathi Rama Mohan Rao, both acclaimed mridangam players. Rajam (who also happens to be sister of flute maestro N. Ramani) had a seven-decade long career as a mridangam player. She had accompanied several eminent artists like M.L. Vasantakumari, D.K. Pattammal and Trichur Ramachandran. I never met her. But the septuagenarian Sumathi ji continues to play and I have had a chance to meet her a couple of times.

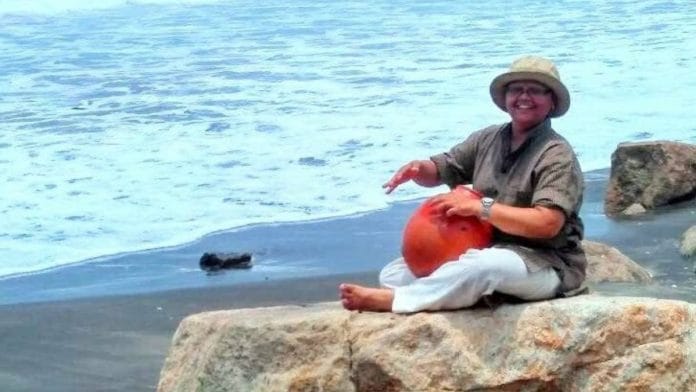

This excerpt from ‘Song of the Clay Pot’ by Sumana Chandrashekar has been published with permission from Speaking Tiger Books.