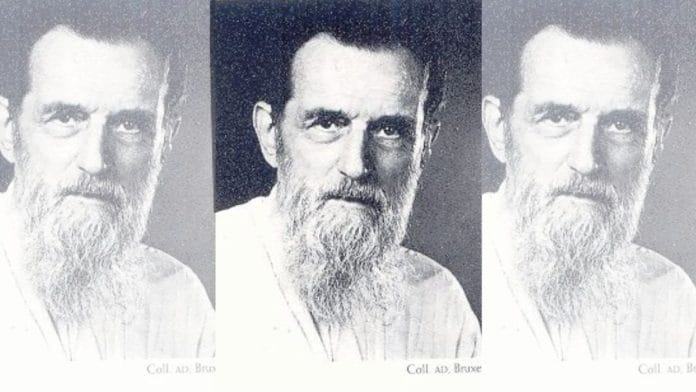

During his lifetime, Camille Bulcke appeared to be an enigma, leaving several of his acquaintances nonplussed to see a devout Christian, an ardent missionary and an ordained priest with such inherent and infinite reverence for Tulsidas and his Rama bhakti. Indeed, Indian spirituality and religious traditions have attracted a fair share of Westerners, who left their homes to adopt India and embrace its religious and cultural practices. This illustrious list includes luminaries such as Annie Besant (England-born Annie Wood), a renowned Theosophist and a prominent campaigner for Indian independence; Sister Nivedita (Irish-born Margaret Noble), who became the disciple of Swami Vivekananda; Mirra Alfassa, or the ‘Mother’ of Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry; and Mirabehn (Madeleine Slade), a follower of Mahatma Gandhi. Undoubtedly, for these foreigners, India’s cultural and spiritual values were the initial attractions, though most of them ended up participating in the independence movement that was pursuing self-respect, self-rule and anti-colonial nationalism.

Camille was an exception; he joined the anti-colonial nationalist struggle but not as a political activist. Instead, he participated as a cultural campaigner seeking the respect and restoration of Hindi to its rightful place, by challenging the hegemony of English well beyond the formal end of British colonial rule. Unlike Sister Nivedita, Mirra Alfassa and Mirabehn, Camille came to India as a Christian missionary, and did not have a living person as his guide, mentor or patron; instead, he chose Tulsidas, a sixteenth-century Hindu devotional poet as his anchor.

Tulsidas as the core of Camille’s personal, literary and spiritual life is all the more puzzling given that the Indian poet did not figure even remotely in Camille’s world when he took the life-changing decision to renounce and become a Christian priest and later to take up missionary work in India. He considered it a divine command to give up worldly affairs and take his priestly vows, drawing inspiration from Father Constant Lievens, the well-known Belgian missionary who served in the Chhota Nagpur region in India.

It was only upon reaching India that Camille witnessed the hegemony of the colonial language, English, over the indigenous Indian languages. It reminded him of his own struggle during his student days for his mother tongue, Flemish, in Belgium, and he developed a natural affinity for the local language, Hindi. It was his prior commitment and personal pledge to oppose language hegemony that inspired him to not just take a firm stand for the honour of Hindi, but convinced him to master the language of the people. It was during the very early stages of learning Hindi that Camille discovered Tulsidas, his sublime poetry, the poet’s devotion to Lord Rama and his spirit of lokasangraha, or universal welfare and universal well-being.

However, despite Camille’s oft-expressed adulation for Tulsidas, should one read only Ramkatha: Utpatti Aur Vikas, also considered his representative work, an astute or even a casual reader would conclude that the Indian poet is just one of the subsidiary sources to this work. Given Camille’s self-proclaimed reverence and professed admiration for Tulsidas, one would imagine that the legendary Indian poet would eclipse all the other raconteurs, poets and writers of the Ramkatha in Camille’s representative work. However, Camille’s most popular contribution to Indology (also his PhD thesis and later book) puts all the limelight on Valmiki’s Ramayana, while Tulsidas and his Ramcharitmanas are a mere sideshow. It would seem an anomaly that Tulsidas, Camille’s most revered figure in all his later works, does not form the core of either his inquiry or his arguments about the Ramkatha.

This contradiction is all the more pronounced in the light of Camille’s affirmation that his esteem for the Ramkatha was but an offshoot of his devotion to the poetic genius of Tulsidas. Therefore, it would be fascinating to explore how he developed such a single-minded and lifelong devotion towards Tulsidas, given that the Indian poet is not a significant presence in Camille’s most celebrated work. Camille aimed to pursue his PhD on ‘Tulsi’s Devotion to Rama’ and started to collect material on this topic (C. Bulcke 2009, p. 14). As the first part of his thesis, he intended to gather sources on the origin and genesis of the Rama story. He managed to collect such a broad range of unexplored material on the genesis of the Rama story that his supervisor asked him to develop only this aspect into a complete thesis. Thus, instead of focusing on Tulsidas and his devotion to Rama, Camille ended up exploring only the pre-Tulsidas phase of the development of the Rama story. Subsequent to the publication of his thesis and book, he began to focus exclusively on Tulsidas and his writings.

Camille explained the significance and import of the Indian poet to his life in one of his most popular articles, ‘The Faith of a Christian: Devotion to Hindi and to Tulsi’. He narrated that several people seeking inspiration from the Sanskrit quotation ‘अध्याहृतानुयोगी मुनिर्जन’, meaning that any question can be put to a sadhu, asked him all kinds of personal questions. ‘Such as: learned though you are, how is it you have such a strong faith in Christ? Though you are a Christian how do you have such devotion to Tulsi?’ (C. Bulcke 2010, p. 134). He was convinced that Christ, Hindi and Tulsidas reigned over his life and regulated his personal, literary and spiritual pursuits. He did not see any contradiction between his faith, the missionary activities and his scholarly work.

This excerpt from Ravi Dutt Bajpai and Swati Parashar’s ‘Camille Bulcke: The Jesuit Exponent of Ramkatha’ has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.

This excerpt from Ravi Dutt Bajpai and Swati Parashar’s ‘Camille Bulcke: The Jesuit Exponent of Ramkatha’ has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.