A Note from the Translator

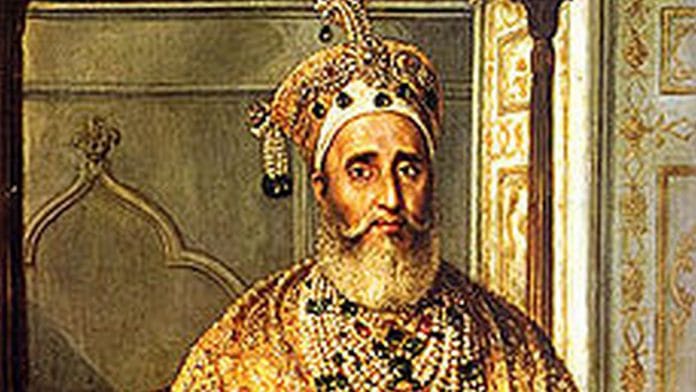

The Uprising of 1857, also called the First War of Indian Independence, was a watershed moment in Indian history. In1857, the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II (r. 1837–57) popularly known as Bahadur Shah ‘Zafar’, the nom de plume under which he composed poetry, was deposed and exiled to Rangoon by the British East India Company, spelling the end of the Mughal Empire. A year later the East India Company was liquidated, and power was transferred to the British Crown by the Government of India Act 1858.

Though much has been written about the Uprising by both British and Indian authors, and it has been the subject of many novels, the fate of the Mughal survivors and its aftermath remained unknown to the public. There were around 3,000royals living inside the Red Fort at the time of the Uprising. These included the Emperor and his immediate family, and the descendants of the previous emperors known as salatin. The Red Fort and the Salimgarh Fort that adjoined it were densely populated. Immediately after the fall of Delhi, the British secured the walled city of Shahjahanabad and the Red Fort. Harsh and punitive punishments were meted out to the Mughal ‘loyalists’ and the royal family. In fact, knowing the importance of the Mughal Emperor and the royal family among citizens of the empire, it was only after dealing with them that the British ensured they took action against other ‘rebel’ centres.

The houses and mansions of the princes and salatins were demolished once the two forts were captured by British forces on 20 September 1857.

Khwaja Hasan Nizami wrote 12 books on the events that unfolded in 1857, all based on eyewitness accounts of survivors. Of these, the most popular collection of stories was Begumat ke Aansoo which was first published in 1922. It had gone into thirteen reprints by 1946 and was also published in Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Bangla and Marathi. However, a complete English translation of the collection has not been attempted so far. Khwaja Hasan Nizami was born in 1879, when many of these survivors were living in and around Delhi. He met them personally and collected their stories. Begumat ke Aansoo is an important document of the events and its catastrophic after-effects on the survivors, the rough and ready and often cruel punishments meted out to the Mughal family often based on false evidence.

Also read: Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal who would rather have been a poet

Excerpts from Begumat ke Aansoo by Khwaja Hasan Nizami

If Bahadur Shah had not been involved in the ghadar [1857 Rebellion], he would have lived the life of a dervish with comfort and ease. But he got caught in the trap set by the rebel forces and spent the last days of his life in great misery.

My mother heard from her father, Hazrat Khwaja Shah Ghulam Hasan, that the day the emperor left the Qila of Delhi, he went straight to the dargah of Mehboob-e Ilahi. He was in a state of despondency and despair. Only a few eunuchs and the porters carrying his sedan chair were with him. His face was lined with worry and his clothes were covered in dust. His white beard was matted with dirt.

On hearing that the emperor had come to the dargah, my grandfather presented himself before His Majesty. He found him leaning near the head of the shrine. A faint smile appeared on his face when he spotted my grandfather. He sat in front of the emperor and asked him about his well-being.

The emperor replied with great simplicity, ‘I had said these accursed rebels were headstrong and trusting them was a mistake. They were bound to go down and take me with them. This is what has transpired. Now they have run away. I am a mendicant, but I am a descendant of the Timurid race, which has the instinct and courage to go down fighting. Even though my ancestors went through tough times, they never gave up hope. But my end has already been revealed to me. I am undoubtedly the last Timurid to sit on the throne of Hind. The lamp of the Mughal dynasty is about to be snuffed out: it shall last only for a few more hours. Why then should I indulge in unnecessary bloodshed? That’s why I left the Qila myself. This country now belongs to God and He can bestow it on whomever He pleases. For hundreds of years, my ancestors ruled Hindustan through force and fear. Now it is time for others to rule. We will become the ruled and they shall be the rulers. There is no reason to mourn, for we too removed someone from the throne and destroyed their dynasty to establish ours.’

On completing his monologue, the Badshah handed over a box to my grandfather, entrusting it in his care. ‘When AmirTimur conquered Constantinople, he acquired this box from the treasure of Sultan Yaldram Bayazid. It has five strands of hair from the blessed beard of our beloved Prophet. It has been passed down in our family as a special blessing. Now there is no place for me in this wide world, and I don’t know where I can take it. I am placing the box in your care as you are the worthiest person I know. These strands of hair have provided much solace to my weary heart over the years. Today, on the most calamitous day of my life, I must part with them.’

My grandfather took the box from the Badshah, and carefully placed it in the treasury of the dargah. The box remains with us even today, and on every twelfth day of Rabi al-Awwal visitors to the dargah might catch a glimpse of it.

Also read: The ruin of Zafar Mahal: Mughal era’s last holdout is now a den of drug addicts and gamblers

[Having discharged his duty towards his precious charge] the Badshah told my nana sahib, ‘I have not had time to eat the last three meals. If there is some food in the house, please bring it for me.’

‘We are also standing at the edge of death and no one has had any time, or peace, to cook. But I will bring whatever I can for you. In fact, why don’t you grace my humble abode with your blessed presence? As long as my children and I are alive, no one can touch you. We will die before anyone can harm you,’ nana sahib said.

‘I am grateful for your kindness, but I will not jeopardize the lives of my pir’s children to defend this old body. I have paid my respects to Mehboob-e-Ilahi, and I have entrusted you with my beloved treasure. Now, if I can eat a few morsels, I will go to Humayun’s tomb. Destiny will fulfil what fate holds in store for me.’

Nana sahib rushed home and asked if there was something to eat. He was told that only besani roti, a chutney made of vinegar, and some relish were available. He took the food on a covered tray and presented it to the badshah, who ate it and thanked god for His mercy.

Thereafter, he left for Humayun’s tomb, where he was arrested and later exiled to Rangoon, where he continued his spiritual pursuits. Until he breathed his last, he was a forbearing and pious dervish.

This tale should serve as a warning to all humans. After hearing it they should give up pride and ego. Only then can man become human.

This excerpt from ‘Tears of the Begums: Stories of the Survivors of the Uprising of 1857’ translated by Rana Safvi has been published with permission from Hachette.

This excerpt from ‘Tears of the Begums: Stories of the Survivors of the Uprising of 1857’ translated by Rana Safvi has been published with permission from Hachette.