A policeman is a very social creature. Working with people, for them, and making a direct impact on their lives is the most satisfying aspect of a policeman’s life. Seeing a policeman engage with the community this way nurtures trust about the police in the minds of the citizenry. They support police work and maintain peace and order in their own communities. This police–public partnership is the leverage that makes it possible for a few thousand policemen to maintain peace in cities of tens of millions. Here’s a story that illustrates this idea.

In Mumbai, before cricket became the one sport to rule them all, football was very popular. In the 1970s, Rovers Cup was one of India’s premier football tournaments. Clubs from all over India participated. And since Mumbai (known as Bombay then) had working populations from all over the country, each club had deep and passionate backing. The Goans supported Dempo and Salgaocar; the Bengalis thronged for Mohun Bagan and East Bengal, the Muslims among them had extra love for Mohammedan Sporting. Mumbai’s textile mills like Mafatlal and Orkay had their own teams. Each of these communities were very vocal about football, and after a few drinks, the passion would boil over into verbal and physical volleys against the opponents of the day. Quarrels and fisticuffs were commonplace.

The Cooperage Football Ground near Nariman Point, now the home of some Mumbai Football League clubs, was the home of Rovers Cup. The 30,000-seater stadium in the heart of Mumbai was always packed to the rafters, and there would be long queues to enter well before the matches started. Stragglers, hawkers, ticket-scalpers and other opportunists added to the numbers and the general melee. Naturally, we deployed a good number of lathi-wielding policemen to maintain relative calm. And since prevention is better than cure, I would strike up conversations among the fans, engage in friendly banter and break up petty squabbles. This served the dual purpose of helping me get a sense of which match was likely to get more heated based on the pre-match debates, and also made me a familiar figure among the regulars, the most passionate fans.

In 1977, Tata Sports Club and Dempo were playing the semi-final of the Rovers Cup. The stadium was packed; the game was in full swing. In the twelfth minute, Tata had possession. The ball was passed into the penalty area, and their forward slipped it in. A goal in the first fifteen minutes. Ten thousand people erupted in celebration. Another ten thousand let out shocked gasps. But then, the referee signalled off-side and disallowed the goal. The celebration and gasps were reversed in the stadium. The Tata team would have none of this. They were not going to be denied the goal. When the referee refused to back down, they walked off the field. Obviously, there were no video replays back then which could’ve helped.

There was stunned silence for a minute or two in the stadium. Then it hit the fans—if the team had walked off, the game would be cancelled, and they would not get their hard-earned money’s worth. This was not okay. Slowly, chants of ‘Paisa vaapas do! Paisa vaapas do! (Give back our money!)’ erupted. Fans of both sides joined in this demand.

A man called Mr Ziauddin was in charge of the Cooperage Ground. He would have none of this, and flatly refused to return any money. The fans’ frustration then literally went up in flames as one fan broke his wooden-plank seat and set it on fire. Others took the cue, and slowly, a large part of the stadium was ablaze. If you remember the sights broadcast around the world from the India–Sri Lanka semi-final of the 1996 Cricket World Cup at Kolkata’s Eden Gardens, this was pretty similar to that. If this continued, not only would the stadium burn down, but Mumbai’s decades-old football tradition would be in danger.

Ziauddin was shocked and started panicking. He tried to shout the people down, but nothing worked. I had to do something. I told him, ‘You must promise that if I stop this arson and save your stadium, you must give refunds.’ Before he could affirm, I snatched a blackboard used for keeping scores, and wrote in large letters, ‘PUT OUT THE FIRE. WE WILL REFUND.’

I held the board above my head and started walking around the ground, also shouting out the message in my loudest voice. I had no reason to think anyone would believe me, a policeman, regarding refunds. It was the passions of 30,000 people against one man trying to restore calm. But I had to try. My naturally booming voice was barely audible even to myself. My throat was going dry, and it hurt from shouting, as did my arms from carrying the big board. Sweat streamed down my body in the heat of the evening. But slowly, one fire went out, then another, and another. People wanted to believe me, and they did. They loved their game, and the stadium. No one wanted it to end this way, and I was giving them a way out. Being a familiar and trusted face helped them to believe me.

The stadium was saved. Ziauddin offered the option of an on-the-spot refund or using the same tickets the next day for a replay of the match. A few hundred took the refund, but most opted to come back.

The next evening, the stadium seemed to be even more packed than usual. As soon as I entered the ground with the other policemen, there was a cheer from a section of the crowd. Then others joined in. There were chants of ‘Zende zindabad! Zende zindabad! (long live, Zende!)’. It was overwhelming. I had to do a lap of the stadium waving to the crowd, acknowledging their cheers like a winning team’s captain. My heart was filled to bursting. I knew then that this support of the people, and the opportunity to help them, was my biggest motivator as a policeman. That evening for me was far more memorable than any other moment in my career.

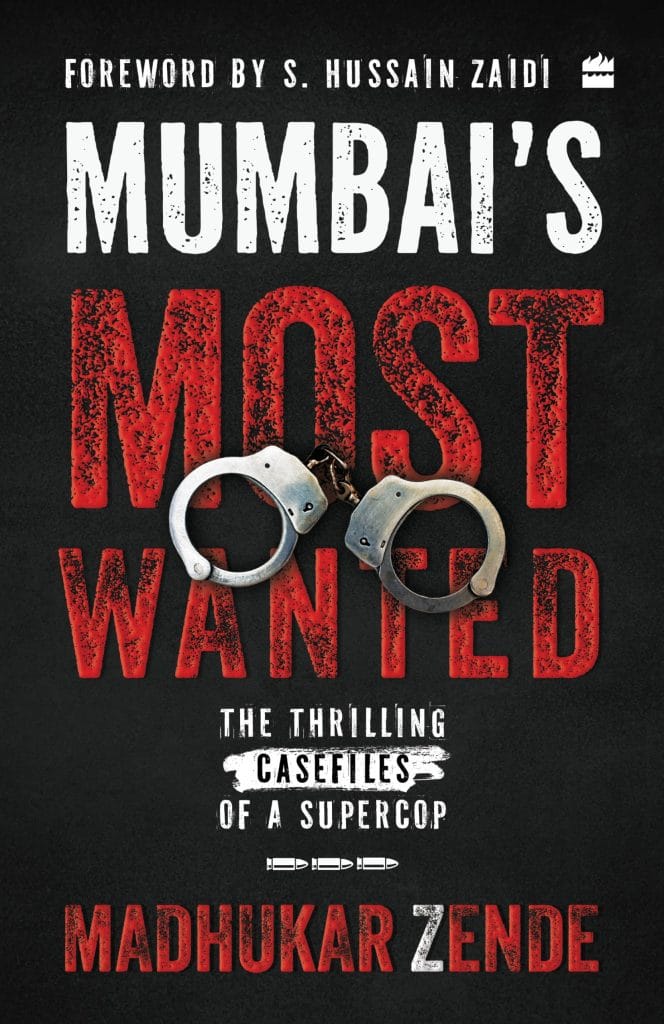

This excerpt from Mumbai’s Most Wanted: The Thrilling Case Files of a Supercop by Madhukar Zende has been published with permission from HarperCollins.

This excerpt from Mumbai’s Most Wanted: The Thrilling Case Files of a Supercop by Madhukar Zende has been published with permission from HarperCollins.