The immigrant Indian revolutionary community in Soviet Russia produced the first communist group, which declared itself to be the communist party of India, though it never became one. In fact, there is conclusive evidence to show that the formation of the communist party was a long and arduous one. It took place in a country with a semi-feudal peasant community making up the bulk of the population and an insignificant proportion of proletariat whose class consciousness was at a low level.

The bourgeoisie, on the other hand, had a certain amount of political experience to go by. The Independent Communist movement in India and similar countries faced considerable difficulties as it emerged. It is worth mentioning that Lenin questioned the very possibility of true proletarian communist parties, committing to the ideology of Marxism arising in these countries. The fact that the first communist group was formed of Indian revolutionary émigrés in Soviet Russia and that the communist party took years subsequently to shape up did attest to the difficulties the emergent communist movement in India had to surmount.

Eventually, it was not through the labour movement that the Indian national revolutionaries advanced towards Marxism. As a rule, they were not connected with it at all and, for the most part, failed to see its significance. But it was through an anti-imperialist liberation struggle and through their affection for the Soviet system of state power, which had become the world’s most important anti-colonialist force and a real base of support for the liberation movement of the people of the east.

In the Eastern European and Asian countries, it was principally national revolutionary democratic intellectuals who formed the first communist groups, laying the groundwork for a broader communist movement. With the passage of time, the national revolutionaries came closer to Marxism, increasingly stimulated by social trends that were gaining ground in the national liberation movement as the working class started independent action in the major industrial capitalist centres of India. Indian national revolutionaries turned to the scientific theory of socialism and to the evidence of its actual application by Russian communists under Lenin’s guidance to see how they had to go about winning their own national independence and resolving their own urgent problems.

In many ways, the influence of the Soviet system had been the foundation for communism in India. This led to the formation of an intellectually alive world order, which thrived on authentic ideology.

It was eventually under the impact of the great October socialist revolution that an organized proletarian vanguardcommunist party began to be formed in all continents. This process started to develop in oriental countries in the specific environment created by colonial oppression and social and economic backwardness. Furthermore, the effect of the October Revolution on the emergence of the communist movement in Asian countries close to the borders of Soviet Russia was particularly appreciable because it was exercised mainly through the working people who happened to be in Russia at that time.

There were a large number of citizens of China, Korea, India, Iran and Turkey in the Soviet Republic in 1917 through 1920. They were simply not visitors or bystanders—in truth, important emissaries of history through their notable influence. In many ways, they were like the pioneers in their respective countries, flagbearers of a promising world order.

The emigrant movement of the Indian revolutionaries reflected the processes of division and unification that were taking place in the Indian liberation movement since it surged up following the first Russian Revolution of 1905. The rise of the liberation struggle in 1905–08 led to a break-up between reformist and revolutionary sections of the movement.

Many of the Indian national revolutionaries who rejected agreement with Britain and called for the overthrow of British domination and for full national independence had to emigrate to various countries of Europe, the Americas and Asia because they were the most ruthlessly persecuted by the British authorities. The Indian revolutionary émigrés were people of different religions, determined in their opposition to the split of the Indian liberation movement on religious grounds and united in battle against British Imperialism.

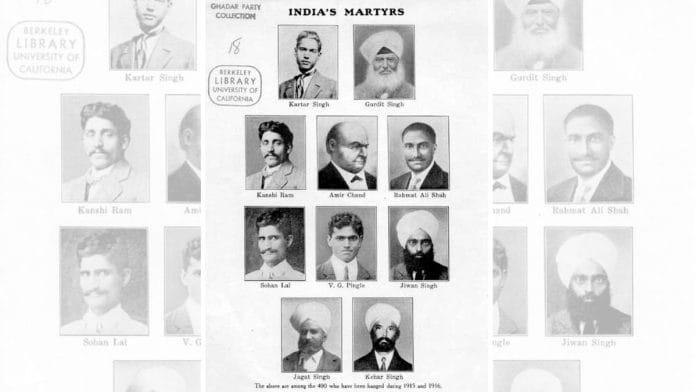

Also read: When Ghadarites supported German ambition of invading India. Kashmir was key to their plan

Before and during World War I, the Indian émigrés had considerably stepped up their revolutionary activities. Having created their fighting organizations and revolutionary centres in various countries of the world, it was easier in their opinion to press for the liberation of India with the help of powers hostile to Britain in the years of an international crisis and exacerbation of inter-imperialist contradictions. This became a pattern all the way through to the Azad Hind Fauj.

The Ghadar Party was created in the US in 1913 under the direction of an outstanding Indian revolutionary, Har Dayal. After Har Dayal’s arrest in 1914, the organization was led by Bhagwan Singh, with Mohammad Barakatullah, a subsequently prominent leader of the Soviet-based Indian immigrant community, as his deputy.

Ghadar established its own centres in the USA, Canada, Argentina, Europe (France, Britain, Germany, Sweden) and Asia (India, China, Burma, Siam, The Philippines). Most clearly, an inspiration for many cadres of revolutionaries, this was the first-ever set of influential Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), much before the term came into vogue.

The greatest amount of work done in the Indian forces outside India, and in India proper, was mostly in Punjab. This orientation of revolutionary activities was due to the firm conviction that it was only the action by individual military units that could start a popular uprising and that the success of that uprising would be ensured by the preceding and succeeding support of powers hostile to Britain. Therefore, they carried on conspiratorial work among small group of revolutionaries and also in selected army units. They hardly thought of conducting mass propaganda work among peasants and workers and did not consider them to be revolutionary and politically conscious. A driving force behind this thinking would have been the military orientation of the native Punjabi, exceptionally proud of his conquest skills.

In mid-1915, the Indian Revolutionary committee in Berlin got Mahendra Pratap and Mohammad Barakatullah included in the German mission of Hentig-Niedermeyer bound for Afghanistan. The German diplomats and Indian revolutionaries did not succeed in co-opting the Emir into an alliance with Germany for joint action against Britain.

But Pratap and Barakatullah made good use of their visit to Kabul. They organized a new emigrant revolutionary centre there on 1 December 1915, the so-called Provisional Government of India in exile, with Mahendra Pratap as President and Mohammad Barakatullah as prime minister. Ubaidullah Sindhi of the Indian Muslim Liberation movement became minister of the interior. He was one of the leaders of the Deoband Underground Organization, which was laying the ground for action against Britain by a volunteer army, recruited in India proper and in neighbouring Muslim countries.

Also read: How photojournalist Kulwant Roy captured India’s transition to freedom

The provisional government strove to organize an allout uprising in India with armed assistance from the Afghan government and independent borderland Pashto tribes. True to their tactic of alliance with anti-British powers to get financial and military support, the Indian revolutionaries in the provisional government looked to Afghanistan and naturally, Czarist Russia.

In 1916, Mahendra Pratap sent two missions to Russia, the first one in March–April and the second one in August–September to get the Czar to commit Russia, either for outright support to prospective Afghan–Indian action against Britain, or at least neutrality. The first mission reached Tashkent, while the other was stopped at Termez—the officials of Turkestan, under instructions from their government, reaffirmed the Czar’s loyalty to the alliance with Britain.

While the first mission led by Mohammad Ali did eventually return safely to Kabul, the second one was arrested by the Czarist authorities of Turkestan and handed over to the British consular general at Meshed. The head of the mission was subsequently executed in Lahore. Moreover, the Czar’s officers in Persia arrested the third mission of the provincial government as it travelled to the capital of Turkey in September 1916 and they too turned the mission over to Britain. Following the February revolution of 1917, the provisional government of Indian revolutionaries once more counted on Russia’s aid. In June 1917, they attempted to contact the Turkestan Committee of the Russian Provisional Government, but the committee refused to negotiate with them and reaffirmed their alliance with Britain. The Great Game at its very best, with shades of deceit lacing every move. Never a clear alliance in view.

There were many Russian social democrats, such as Kirill Troyanovsky, who were in close contact with Indian revolutionary workers. However, it was Mikhail Pavlovich who did the greatest amount of work in Paris between 1909 and 1914. This was just before the shadows of the Great War engulfed the continent.

It is very difficult to imagine how strong was the sentiment with which the Indian revolutionaries saw the surrounding world. For example, the slogan of the Soviet government, ‘Down with Capitalists’, was interpreted by the Indian revolutionaries not only as an appeal of the overthrow of all bourgeoisie, including their own national bourgeoisie but also as an appeal against the British domination of India.

Besides the organized Indian émigrés, it was the unorganized cadre that played a pivotal role in India’s independence. Scores and even hundreds of individual Indian patriots streamed into Soviet Russia in addition to politically organized groups of Indian national revolutionaries. It was really challenging to travel across Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush into Soviet territory with Basmachi bands on the prowl and the civil war still raging.

The largest proportion of Indians on their way to Soviet Russia, primarily Soviet Turkestan, consisted of representatives of the Muslim wing of the National Liberation in India, those involved with the Caliphate movement. Barakatullah later described the real reason for the pilgrimage of a considerable number of Indians into Soviet Russia: ‘Many, although they didn’t know what Socialism or Communism means arrived in Russia solely because of their enthusiasm and love for Russia, for they had learnt that Russia is a friend of Turkey and India.’ This friendship continued much later over the decades, even during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971.

This excerpt from ‘Comrades and Comebacks: The Battle of the Left to Win the Indian Mind’ by Saira Shah Halim has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Comrades and Comebacks: The Battle of the Left to Win the Indian Mind’ by Saira Shah Halim has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.