In spring 2014, six months into the expedition, the ASI team knocked on V. Balusubramaniam (Balu)’s door in the village of Silaiman. V. Vedachalam, the epigraphist who had advised Amarnath to climb the hill in Madurai, had also facilitated this visit. Balu and Vedachalam had spent much of their youth cycling around the area in search of old artefacts. Sparks flew instantly between old and new friends. The men discovered they had more in common than a passion for ferreting out black-and-red ware pottery from the ground. Amarnath’s mother and Balu’s sister-in-law had been colleagues in the Tamil department in a women’s college in Palani. Phone calls were made to renew old friendships as everyone settled into Balu’s living room to catch up.

Balu was a freelance explorer in his own right. In the late 70s, Balu, a history teacher with a ‘get to know the history of your own village’ approach, urged his students to leave their classrooms and explore the village. The students set off in search of old items and returned with a coin from Chola King Rajaraja I’s reign, a few beads, and terracotta figurines from the twelfth–thirteenth centuries ce, and even a skull that had once lived in Balu’s living room. It was only when the landlady they rented from objected to this new non-living tenant that Balu collected all the artefacts and walked over to the Keeladi Government School. There, he dragged a broken bench to one side of a noisy classroom that was already short on space and neatly arranged everything on it. He cordoned it off with a simple rope and called it the ‘History Corner’. The school was so small that it lacked a science lab and a map to show historical sites, but that did not deter him.

In Balu’s living room, Amarnath asked him about the artefacts. Where had the students

found them? He looked at Balu for geographical clues, as Balu scratched his head. Forty

years had passed since his students had gone searching for artefacts. Balu

remembered the area had been a dry piece of land back then, known locally as a punjai

medu but over time it had transformed into a lush coconut grove, making it almost

unrecognizable.

The team regrouped at a tea shop in the village of Keeladi, just off the Madurai–

Rameswaram Highway. Next to them, a lorry driver named Maharaja was whiling away

his time, partly sipping tea and partly eavesdropping. Despite the team’s wanderings, it

had been a dull day on the job, and they had stopped at the tea shop to take stock. Tea

shops in rural India were both a source of energy and information; even policemen

occasionally dropped by looking for tips. The team engaged in a game of reminiscing.

Maharaja, the lorry driver, excitedly interrupted to reveal he had been eavesdropping. He

told the archaeologists about the grove from where he routinely transported coconuts to the wholesale market. He had seen many broken pieces of terracotta pots on the

ground there.

The thing about archaeological discoveries is that they are often serendipitous. A

chance finding while stepping on thorns, asking a passer-by, or cycling the same route

every weekend. In this case, a man named after a king overheard a stray conversation.

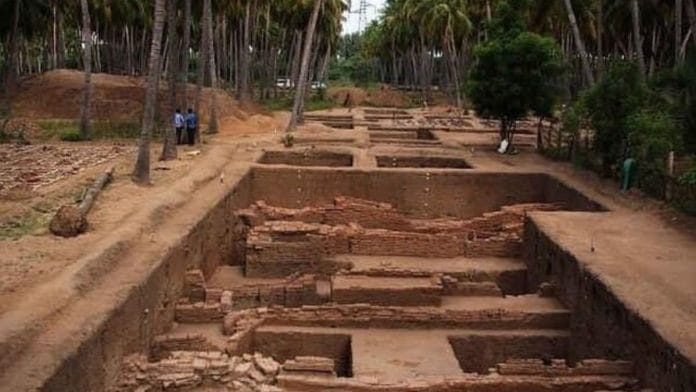

As soon as the ASI team entered the grove, Amarnath and his assistant archaeologist

looked at each other in disbelief. The ground was strewn with tons of potsherds. It was

unusual to find such a large quantity of pottery at a single site. The men had been

trudging along the river for six months in the sun, hoping to find a habitation site, and

only uncovering bits and pieces here and there. Here, they had firmly entered Early

Historic territory, with potsherds strewn about in large numbers – a solid clue for a

habitation site.

Also read: The fantastical Buraq—the Prophet’s ride to heaven

The day’s surprises did not end there. The network of Balu’s students extended

everywhere; they were even present at the grove. Two of them, now middle-aged men,

operated a pump near a large well inside the grove. Dileep Khan and Chandran were

thrilled to see their former history teacher and insisted on marking the reunion by

drinking tender coconut water. With a sharp sickle, Chandran nipped the tops of the

coconuts, making small holes in them. The impact shook the water inside. Balu

introduced the men to the archaeologists. Coconuts passed hands.

‘Sir, when they excavated mud from a place nearby, we found a brick wall,’ Chandran

told Amarnath. A rogue JCB machine digging the earth to service a nearby brick

chamber had unearthed a standing wall.

‘What? You’ve found a wall?’ Amarnath asked, surprised.

‘Yes Sir, one with big bricks. Come, I will show you.’

Chandran led the team to an area entirely hidden by thorn bushes. The path was lined

with pottery sherds. ‘Whoever dug it up found a grinding stone and some pots, but the

landowner threw them away,’ Chandran said.

Amarnath put his team to work, asking that the area be cleared of thorny bushes. The

men jumped into the ditch to hack away at the undergrowth and scrape, pry, and yank

out one whole brick. Around the wall, the mud had been scooped out by the JCB

machine to collect raw material for making deep maroon rectangular bricks – yet

another serendipitous find. Even today, the coconut grove is surrounded by brick

chambers, and mud is scooped out to meet the growing demands of modern housing.

His colleagues handed Amarnath the flattened brick, which had a pinkish tone. It was

larger than the bricks found at Harappan sites. It also closely resembled those that Wheeler had seen in Arikamedu. It would turn out that Arikamedu and Keeladi were

once connected through an elaborate labyrinth of trade routes that cut across ancient

South India. It was how the tinais traded with one another.

The brick was added to the collection of expedition goods. It was measured,

documented, and put away in the back of the sedan. The team had to press on. They

had to navigate the rest of the Vaigai’s downstream. Besides, time was running out. It

was nearing August, weeks away from shipping a well-crafted proposal to the ASI’s

headquarters, seeking permission to dig a chosen site in Tamil Nadu. Any application for

an excavation licence, whether by the ASI, a state archaeology department, or a

university, had to be submitted to the Indian government for evaluation by a standing

committee of the Central Advisory Board of Archaeology (CABA). The CABA, chaired by

the union minister of culture, was the final deciding authority on whether a site could be

scientifically probed. Amarnath’s team decided to nominate Keeladi for the dig; it

seemed to have ‘potential’ and was worth taking a chance on.

Keeladi had already cast its spell. Even as they navigated downstream, the team kept

returning to the grove, exploring it from different directions. On each visit, they found the

area littered with a variety of potsherds unlike any they had seen before. These ranged

from fine to coarse black-and-red ware, black ware, red-slipped ware, red ware, and

coarse red ware with decorative and incised patterns. The discovery of these potsherds

was a game changer, revealing diverse trade within and outside India, particularly with

the West Coast and the Romans. Although they had identified 293 potential sites along

the Vaigai, they narrowed the list to 100 and eventually shortlisted three sites, all within

50 km of Madurai. Keeladi stood out. They did not yet know that the tall trees of the lush

coconut grove had perfectly preserved an urban centre under it. ‘Nooru-la onnu than

Keeladi,’ Amarnath declared. Keeladi was one in a hundred.

This excerpt from ‘The Dig’ by Sowmiya Ashok has been published with permission from Hachette India.

This excerpt from ‘The Dig’ by Sowmiya Ashok has been published with permission from Hachette India.