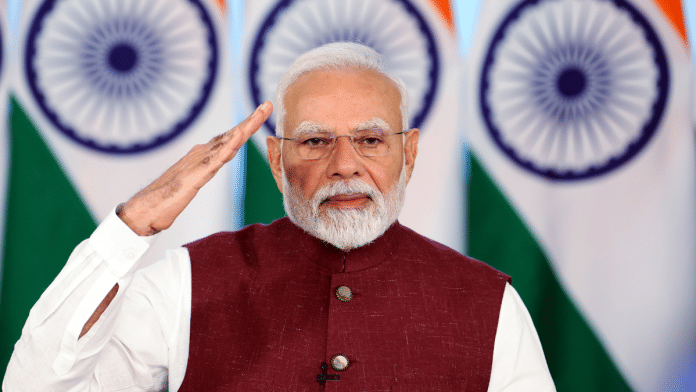

PM Modi understands the importance of India presenting itself to global powers as a regional leader—one that enjoys the goodwill and support of its neighbours. He made strenuous efforts in the last decade to strengthen bilateral ties with all the neighbours, including Pakistan. Similar to PM Vajpayee’s 1999 bus ride to Lahore, PM Modi made an unscheduled surprise visit to Pakistan on Christmas Day in December 2015. With just a few hours’ notice, he landed at Lahore Airport to meet his Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif; then he took a helicopter ride to Sharif’s Raiwind residence to attend his granddaughter’s wedding. Although the visit did not have the desired results, it showcased PM Modi’s sincerity in building strong ties even with an adversary like Pakistan.

In an effort to build a strong regional collaboration, PM Modi invited leaders of SAARC countries to his first oath-taking ceremony as prime minister in May 2014. Leaders that attended the ceremony included Hamid Karzai, president of Afghanistan, Tshering Tobgay, PM of Bhutan, Abdulla Yameen, president of the Maldives, Navin Ramgoolam, PM of Mauritius, Sushil Koirala, PM of Nepal, Nawaz Sharif, PM of Pakistan, Mahinda Rajapaksa, president of Sri Lanka, and Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury, speaker of the Bangladesh National Assembly. During his second swearing-in ceremony in May 2019, leaders from all the neighbours (except Pakistan) were present.

Building Brotherhood and Bonhomie

Despite all these efforts, India’s neighbourhood remains a challenge for the country’s strategic elite. China’s growing influence, coupled with the tendency of regional leaders to play both sides, is testing India’s resolve to establish itself as a regional power. Some strategic thinkers even suggest that India should look beyond South Asia since ‘in contemporary Indian strategic thinking, South Asia is at best a small place and at worst a limitation.’ They argue:

There is little value for India in pouring in resources to either regain exclusive primacy or balance China in a space in which it is geopolitically weaker and somewhat contained. Although New Delhi’s concerns about Beijing’s growing power are understandable, frantic attempts to win back South Asia or compete with China for regional dominance are unlikely to work. Another option available to India is to work with China in the region, as many of India’s neighbours would prefer, but it won’t be too long before an ambitious and aggressive China seeks to relegate India to the rank of a second-rate power in South Asia.

Obviously, India cannot and should not take such a drastic view about its immediate neighbourhood, not only because of geostrategic reasons but also due to the long and established geocultural and civilizational bonds it enjoys with the people in the region. Most of India’s neighbours are civilizational cousins, sharing historical connections that can never be erased from popular memory. India should strive to build on that natural sentiment of brotherhood and bonhomie to develop a strong immediate neighbourhood coalition on the principle of sovereign equality and civilizational fraternity.

Also read: India’s Constitution governs its destiny. It has framed the way we live: Ram Madhav

Regional Multilateralism in the Extended Neighbourhood

Today, the world is marked by several minilateral regional organizations. India is also a member of several of them, besides of course being the founder member of two—SAARC and BIMSTEC. India’s membership in organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), BRICS and IORA, as well as regional arrangements like the Quad, makes it a participant in regional multilateralism. However, to emerge as a regional power, India needs to build a functional regional multilateralism with itself in the driver’s seat, rather than being ‘also there’. The Indian Ocean Region is the natural region in which India strives to build such a coalition of like-minded nations in the twenty-first century.

Almost invariably, school students used to be taught that Sri Lanka and Bangladesh were India’s Indian Ocean neighbours. Kanyakumari, the southern tip of Tamil Nadu, was regarded as India’s territorial boundary. This continental mindset refuses to recognize the fact that Indira Point—a village in the southern part of the Nicobar district island chain—is the southernmost tip of the Nicobar Islands, and should be called the boundary of India. From this village, the Sabang district of the Aceh province in Indonesia is just 145 kilometres away, thus making Indonesia also a border country with India.

Once India discards its continental mindset, and adopts the Indian Ocean as its natural playground, countries from Malaysia to the Maldives and Madagascar will become its neighbours. Just as the South China Sea doesn’t belong to China alone, the Indian Ocean is not India’s exclusive ocean zone. Yet it is India’s natural zone of influence due to historical, cultural and civilizational linkages that it enjoyed in the region, stretching from countries in today’s ASEAN region to East Africa.

In a well-researched and eye-opening account of the influence of Indian cultural and civilizational ideas on the countries in Southeast Asia, G. Coedes writes:

Indian-style kingdoms were formed by assembling many local groups—each possessing its guardian genie or god of the soil—under the authority of a single Indian or Indianised native chief. Often, this organisation was accomplished by the establishment, on a natural or artificial mountain, of the cult of an Indian divinity intimately associated with the royal person and symbolising the unity of the kingdom. This custom, associated with the original foundation of a kingdom or a royal dynasty, is witnessed in all the Indian kingdoms of the Indochinese Peninsula.

It reconciled the native cult of spirits on the heights with the Indian concept of royalty, and gave the population, assembled under one sovereign, a sort of national god, intimately associated with the monarchy. We have here a typical example of how India, in spreading her civilisation to the Indochinese Peninsula, knew how to make foreign beliefs and cults her own and assimilate them—an example that illustrates the relative parts played by Indian and native elements in the formation of the ancient Indochinese civilisation and the manner in which these two elements interacted.

This excerpt from Ram Madhav’s ‘The New World: 21st Century Global Order and India’, has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from Ram Madhav’s ‘The New World: 21st Century Global Order and India’, has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.