The managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Christine Lagarde, once said that there are three types of countries in the world:

- Those that are growing

- Those that are not growing, and

- Those that are shirking (i.e., not working)

The trouble about India is that we presently have all three types located at different places in this vast subcontinent, so which part of it should I mention? If one has to generalise and say something about the nation as a whole and its present condition, I cannot do better than quote the famous Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw. Being a playwright, he once went to see a Shakespearean play at a theatre. When he came out, he was asked how he enjoyed it, and this was his reaction: “The play was a great success. But the audience was a failure.”

Applying this typically Shavian sentence to current affairs, I would say: “The nation is a great success, but it is the people (in some parts of it) that are a bit of a failure.” This is reminiscent of the apocryphal story of the Great Lord Brahma. The nations of the world made representations to him, protesting against giving to this vast subcontinent the longest of rivers, the highest of mountains, the deepest of oceans, and the densest of forests and thus discriminating against all other countries of the world. And Lord Brahma smiled and said: “Yes, you are right. But to balance everything, see the people that I have put there!”

A nation is not merely about geography or history but about the people that inhabit it. And there are simply far too many—far too many disparate people. There were only 330 million people when India gained independence and when the Constitution of India was drafted. It was far more manageable then. We are now 1.3 billion plus and it is expected that the growth of the population will not stop till the year 2030. This, then, is the mother of all problems. Our infrastructure—never great at the best of times—has simply not kept pace with our exploding population. And along with all this, there is so much hypocrisy as well, illustrated by the barber’s story. Most of you must have heard the barber’s story, which is already doing the rounds on the internet.

While cutting a cabinet minister’s hair, the official barber asks: “Sir, what’s this Swiss Bank issue?”

The minister shouts: “You are cutting my hair or conducting an inquiry? Stop asking!”

Barber: “Sorry sir, I just asked.”

The next day, while giving a haircut to another minister, the barber once again asks: “Sir, what’s this black money issue?”

This minister also shouted at him: “Why have you asked me this question?”

Barber said: “Sorry sir, I just asked.”

The following day, the CBI (Central Bureau of Investigation) sends a team to interrogate the barber.

CBI: “Are you an agent of Baba Ramdev?”

Barber: “No, sir.”

CBI: “Are you the agent of Anna Hazare?”

Barber: “No sir.”

CBI: “Then while cutting hair, why do you ask these VIPs about Swiss Bank and black money issues?”

Barber: “Sir, I don’t know why, but when I ask about Swiss Bank or black money, their hair stands up straight and that helps me to cut the hair easily. That’s why I keep asking.

Also read: Fali Nariman was India’s ‘conscience-keeper’. He spoke truth to power—and admitted mistakes

On a serious note, as I see it, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of democracy for our nation as an experiment of unity amidst diversity has been only partially successful. You will remember what he wrote in his book The Discovery of India, which inspired many students of my generation when we were in college or university. Writing in the quiet seclusion of a British prison in 1944 (during Nehru’s ninth term of imprisonment for revolting against the British), he contemplated “the variety and unity” of India.

“In ancient and medieval times, the idea of the modern nation was non-existent, and feudal, religious, racial, and cultural bonds had more importance. Yet I think that at almost any time in recorded history, an Indian would have felt more or less at home in any part of India and would have felt as a stranger and alien in any other country. He would certainly have felt less of a stranger in countries, which had partly adopted his culture or religion.

Those, such as Christians, Jews, Parsees, or Moslems, who professed a religion of non-Indian origin or, coming to India, settled down there, became distinctively Indian in the course of a few generations. Indian converts to some of these religions never ceased to be Indians on account of a change of their faith. They were looked upon in other countries as Indians and foreigners, even though there might have been a community of faith between them.”

This was Nehru’s vision of our nation. It approximated to that of his friend, the British author E. M. Forster, who had visited the subcontinent. But he was a bit critical of Indian democracy and gave it only two cheers, not the customary three: “So, two cheers for Indian democracy: one because it admits variety and two because it permits criticism. Two cheers are quite enough: there is no occasion to give it three.” This is why Nehru’s vision of democracy in this great nation has only partially succeeded.

It was with the promulgation of India’s Constitution on 26 January 1950 that the Indian nation was truly born, bringing, for the first time in over 2,000 years, geographical and political unity in a vast subcontinent. Not since the time of Chandragupta Maurya and his immediate successors had Hindustan been under one ruler or government.

A contemporary assessment of the record of the first sixty-five years in the life of a nation is bound to be faulty. It lacks perspective. It does not have the historical advantage of time and distance. Yet, over the past six-and-a-half decades, the Indian experiment with unity amidst diversity has been continuing—a major plus point during a period when the country has witnessed much economic, political, and social upheaval, but during which it has also experienced material progress with remarkable achievements in the fields of medicine, science, and technology.

However, we have not yet resolved the complexities that lie buried in the great but elusive doctrine of equality spelt out in Article 14, which provides that: “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.” The tension between the commitment to non-discrimination as well as to equality was poignantly expressed by Prime Minister Nehru during the debate in Parliament at the time of the Constitution First Amendment Bill (in May 1951):

“We cannot have equality because in trying to attain equality, we come up against some principles of equality . . . We cannot have equality because we cannot have non-discrimination because if you think in terms of giving a lift up to those who are down, and out, you are somehow affecting the present status quo undoubtedly. Therefore, you are said to be discriminating because you are affecting the present status quo. Therefore, if this argument is correct, then we cannot make any major change in that respect because every change means a change in the status quo, whether economic or in any sphere of public or private activity. Whatever law you may make, you have to make some change somewhere. Therefore, we have to come to grips with this subject in some other way.”

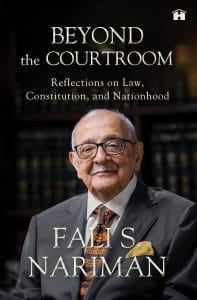

This excerpt has been taken from ‘Beyond the Courtroom: Reflections on Law, Constitution, and Nationhood’ a collection that spans the entirety of Fali S. Nariman’s distinguished career.

This excerpt has been taken from ‘Beyond the Courtroom: Reflections on Law, Constitution, and Nationhood’ a collection that spans the entirety of Fali S. Nariman’s distinguished career.

People ❌❌❌

Political and elites , Social Elites , Bureaucratic Elites + Seduced by Business Elites = SYSTEM FAILURE AND FOSSILIZED SOCIETY + PEOPLE WITH STRONG RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

Fali nariman was a product of an elite section of society blaming people is intellectually & morally DISHONEST !!!