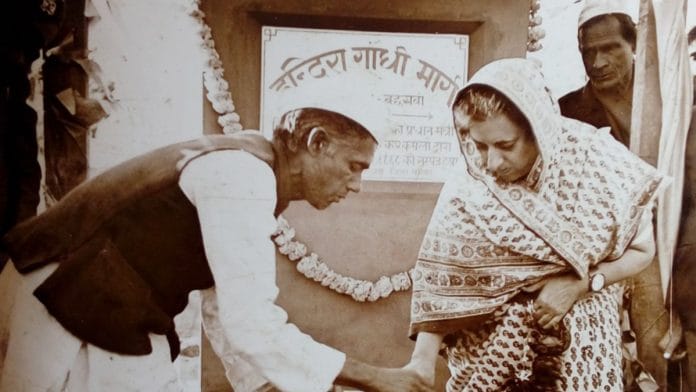

After her release, Mrs Gandhi came to Bombay like an ordinary citizen. Every time she visited Bombay, I made sure she did not stay anywhere else but my home. So I would fetch her from the airport and cook for her. Often, I used to make Gujarati dishes like kadhi and khichhri for her, which she loved.

One day, when she visited our house, she appeared exhausted. I offered to press her legs, despite her initial reluctance, explaining that doing so would make me happy. After a brief silence, she warned that the government would harass me for taking care of her and meeting her in public. I said, ‘What can they do? At most, they can hang me. They are already harassing my husband, attacking his business. But I cannot be disloyal to you.’ I told her I was sure someday she would be back again at the helm of things: ‘The very people who abandoned you will be back tomorrow. Unfortunately, I have a feeling they will be in and I will be out. But that thought does not really keep me up at night.’

My youngest daughter, Asma, was about three years old at the time. Mrs Gandhi was very fond of her. Asma was a confident, talkative child who loved to spend time with her. One day, she came in with a voter slip we had received. It had party symbols. Mrs Gandhi’s breakaway faction, Congress (R), had opted for a cow with a suckling calf. In 1978, after the second split in the Congress, she had chosen the open palm symbol for her new outfit, the Congress (I) or Congress (Indira). Asma took the voter slip to her and said, ‘You will milk the old cow with this new hand.’ Mrs Gandhi was astonished: ‘What is she saying?’ I explained, ‘She is saying that a hand is important even for milking a cow.’ She started laughing. Mrs Gandhi was patient and gentle with my children. She was always respectful, no matter how young a person was or whether she understood their logic or not—a quality she certainly shared with her late father.

I still remember vividly one rain-soaked July day in 1977 in Delhi, when she gave me a lesson on surviving in a world where betrayal and trust, rise and fall were the norm. She was out of power then. When I arrived from Bombay to meet her, she was closing the drawing room door against the rain after bringing me inside. I had never seen her looking so tired. ‘What has happened?’ I exclaimed. She was quiet for a long time. I searched her face for clues. She did not smile or grimace, just sat still.

‘I was Prime Minister, but I did not know the nuances of running a country,’ she said. Bit by bit, she told me how people she had faith in—from her trusted bureaucrats and advisors to a Bengal politician and friend—tried to control her. When she began to break free from their shackles, and take her own decisions, they wanted to teach her a lesson. Their politics of patronage tipped her towards her downfall.

She came back, of course, but I always marvelled at how she had changed. This time around, she was tough, shrewd, ruthless and skilled in the use of power.

This excerpt from ‘In Pursuit of Democracy: Beyond Party Lines‘ by Najma Heptulla has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from ‘In Pursuit of Democracy: Beyond Party Lines‘ by Najma Heptulla has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.