The Partition of Bengal in 1905 spurred acts of rebellion that gave Bengalis a means to prove they could be fearless.

Hatibagan, 139 Cornwallis Street, Calcutta,

Early Twentieth Century

Calcutta, the capital of the province of Bengal, was once known as the Second City of Empire. Like London, the First City of Empire, it sat astride a river, the Hooghly, that carried traffic rivalling the Thames. For most up-and-coming Bengali youth of the city, and the handsome and quick-witted Sudhindranath Datta most certainly was one, attendance at Oxford or Cambridge, combined with access to unlimited credit, entitled them on their return to full membership in the high echelons of the Anglo- Bengali elite, otherwise known as the Set. Perhaps because the First World War had prevented Sudhin from attending Oxford, he tended to cast a gimlet eye on his milieu.

Following British traders with imperial pretensions, members of the Set built homes that mixed classical motifs with abandon. Whimsical palaces and stately homes were crowded with Empire sofas, gilded clocks and candelabras. The walls displayed copies of sentimental paintings by Landseer and Leighton. In Sudhin’s maternal grandfather’s home, after-d inner music recitals were held in a Paris- style salon, accessorised with nymphs made of alabaster, porcelain from Sèvres and Dresden, and a billiard table. Family libraries of the Set boasted calf-bound copies of Tennyson, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, illustrated folios of Shakespeare and the entire run of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels, reflecting the Set’s boundless respect for the worthies of English literature. Many also acquired a taste for English mustard, marmalade, cheese and roast beef. They kept exotic birds, bred dogs and racehorses, and dressed their bearers in whiter liveries and larger turbans than the English had theirs wear. Prodigal sons returning to Calcutta after a ruinous fling at Oxford introduced themselves loftily as ‘England returned’. Deprived of cutlery, they ate their rice with ladles in run-down mansions mortgaged to pay for their English airs.

Though Bengalis relished their halcyon days at Cambridge or Oxford as much as anyone, they were destined to always fall short of that exemplar, the English gentleman himself. For Calcutta’s English residents, the Bengalis’ cultivation of English habits was more evidence, should more be needed, that their rule was the destined natural order. They granted Bengalis a kind of imitative intelligence as well as a capacity for breeding more and more Bengalis. But unlike the manly warrior races of the North- West Frontier, the Bengali was believed to lack the spirit, physique and sense of honour required of a ruling race. Consequently, the anglicised Bengali was reviled and ridiculed.

‘By his legs you should know the Bengali,’ Winston Churchill’s favourite globe-trotting journalist G. W. Steevens wrote. Whereas an Englishman’s legs were straight with a tapered calf and a flat thigh, the Bengali had the skin- and- bone leg of a slave. ‘Except by grace of his natural masters,’ this writer concluded, ‘a slave he always has been and always must be.’ Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, another author whose violent prose style Churchill did his best to emulate, agreed. The Bengali was ‘thoroughly fitted by nature and by habit for a foreign yoke’. A British Resident once pointed out the perfidy of hymning the praises of liberty and democracy to Bengalis when everyone knew their realisation was unlikely. Think of the bitterness, hatred and resentment that will eventually arise, he warned. ‘If the baboo had a soul, it might well demand a reckoning.’

Bengalis had met the arriving waves of eighteenth-century Englishmen with little of the hostility or indifference the East India Company would encounter elsewhere. Initially, baboo or babu simply referred to an English- speaking Bengali clerk. Yet while Bengalis may have begun as clerks, they quickly progressed to revenue agents, solicitors and High Court judges. As Bengalis ascended these rungs, English mockery of the baboo facility with the English language became as unrelenting as the contempt for the figure he cut. ‘What milk was to the cocoa-nut,’ Lord Macaulay quipped, ‘Dr Johnson’s Dictionary is to the polysyllabic baboo.’ Similarly, Bengalis were ‘quick to discern the fire of ideas behind the smoke of guns’, whether that was Darwin’s theory of evolution or the rights of widows to remarry. That the conquered should so quickly embrace the language and notions of the conqueror was curious, but that is what happened and Bengalis could argue all night as to why this was. The simplest answer was the most obvious. They were poets and philosophers. They had minds that liked to roam where their lives could not.

Sudhin believed that Viceroy Curzon’s 1905 decision to partition Bengal was the result of confusing this Bengali embrace of English fashions, language and ideas with an abandonment of Bengali ones. As the line Curzon drew divided the largely Muslim eastern half from its largely Hindu western half, Sudhin also understood that the viceroy wanted to empower Bengali Muslims, encourage their loyalty to and identification with the Raj, while sowing suspicion of their Hindu brethren. In this way the babu, with his English pretensions and the mounting political aspirations that accompanied them, might be isolated. It was also true that the viceroy partitioned Bengal simply because he could.

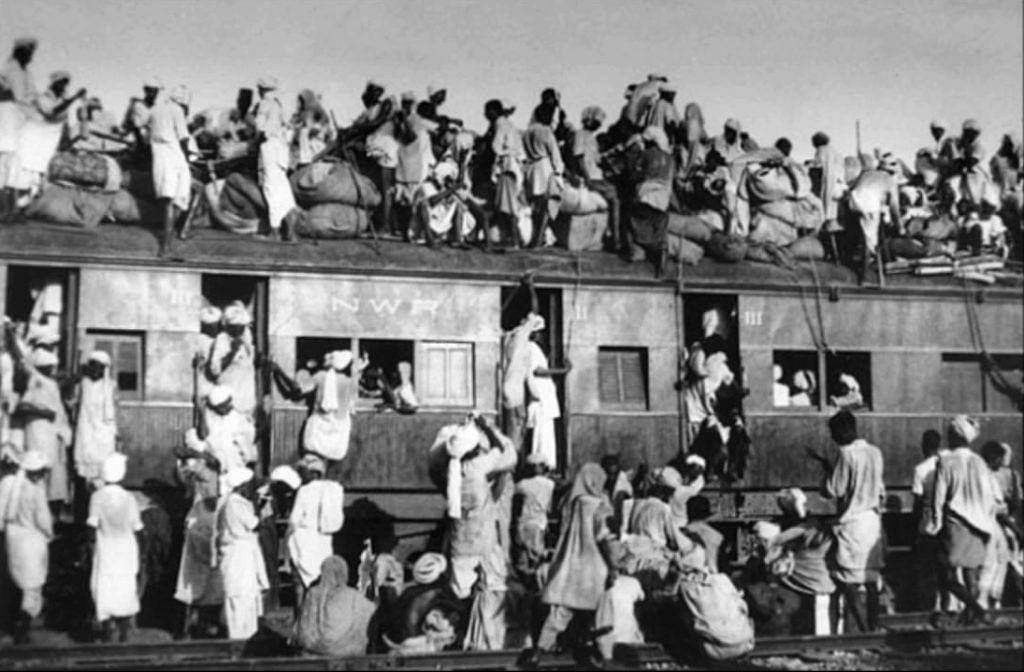

It was a fantastic miscalculation. A boycott was called; bonfi res of Manchester cotton and English goods burned at crossroads throughout Bengal. Swadeshi – self- suffi ciency – was proclaimed. Prefi guring Gandhi’s later call for non-cooperation, the well-heeled and powerful bhadralok class left government service, withdrew their children from educational institutions, and deprived the courts of solicitors. The Raj was paralysed. Lastly, someone tried to assassinate the British governor of the new state of West Bengal. That and other acts of terrorism gave Bengalis a means to prove they could be fearless; they, too, had a sense of honour. In this way ‘baboo’ ceased to denote a figure of ridicule and came instead to refer to an out- and- out traitor, soon encompassing any educated Indian with nationalist leanings.

The partition of Bengal proved the undoing of one of Sudhin Datta’s many uncles. In 1901, this uncle had led a ten- mile- long barefoot cortège mourning the death of Queen Victoria. He worshipped the liberal philosophies of John Locke and John Stuart Mill. For this uncle, however, the presumption that an attachment to things British trumped his love for Bengal was intolerable. His outrage over partition was such that he impetuously forked out twenty thousand rupees to an unlicensed barrister who promised to shoot the viceroy on his behalf. Of course the fellow disappeared with the money and Curzon returned to England unharmed.