Good girls don’t go to Miranda House.’

In 2003, when I qualified for the written test to be admitted to BA Honours English Literature, my North Indian conservative family was not happy. Why would you not do engineering or medicine like other girls? How will you get married? Women with a BA degree are not even considered suitable for that. That too, five hundred kilometres from Lucknow, in Delhi. This college turns women into disobedient, unconventional, rude women that no one likes in this ‘society.’ It is because of the persistent support of my mother and brother, despite many opposing voices, that I landed up in Miranda House in July 2003.

I owe my life to the next three years at Miranda House. I hadn’t read a single English book except the ones in the school syllabus until that point. The first book I ever read was Pride and Prejudice, taught to us by Angela Koreth, who was often called ‘Anjali Kaur’ by the college staff. Angela had strict rules in her class: don’t bring plastic bags that make noise, if the folks in the corridor or the next class are disturbing yours, go out on your own and ensure silence—no one is doing that for you except you; and don’t put up with violence from boyfriends. I loved Angela’s classes for her acerbic ’quotable quotes’, and I took copious notes.

In 2004, a female student was brutally assaulted by a PG owner in Hudson Lane and thrown out in the thick of the night. Our anger and helplessness had to be released. All the teachers in the English department, then—Ira Singh, Manju Kapur, Indira Prasad, Svati Joshi, Sharmila Purkayastha, Saswati Sengupta, Deepika Tandon, and Angela Koreth—worked in tandem, consciously or not, I don’t know, to help us channelise our emotions. Overnight, we had a memo for all PG owners on the North Campus, enumerating the ‘dos and don’ts’, and terms of accommodation. We organised a march across North Campus that surely sent shivers down many PG owners.

Also read: What amounts to cruelty in Indian divorce cases—not wearing mangalsutra, sindoor

The point was also that not many women like me – women who were staying away from their families for the first time and dealing with a lot of patriarchal pressure to uphold ‘honour’ and ‘values’ – participated. This event was one of the first guiltless acknowledgements of my being in this world as a woman who thinks and speaks. It was an assurance that just because I am a woman, my self-worth should not be less than that of others. That a woman’s body, or the time she is out in public spaces, or what she wears or thinks, is her and her business alone. She can speak for herself and many others like her publicly. Who lets a nineteen-year-old believe that she has agency? So, this was big.

The classical texts we were taught or the popular fiction paper that I took, where we tore James Bond to pieces for its misogyny and Gone with the Wind for its racism, even when it had a heroine who, in her way, conquered the world—everything—seemed political, demanding accountability and change.

…

In July 2004, twelve women from Imphal protested naked in front of the headquarters of ‘Assam Rifles’ with the hoarding ‘Indian Army Rape Us’. I had never met a person from Northeast India in Lucknow. My coursemates in college in Delhi were the first ones. This is where I learnt about AFSPA and questioned my idea of nationalism. The women’s protest against the rape and murder of a thirty-two-year-old woman in Manorama and the experiences shared by my classmates exposed my blind spots as a North Indian from the cow belt. And then, several times over, in my desperation to seem less ignorant, I confused the names of many North-Eastern clothes and got scolded on how not all North-East India is homogenous. I now value it so much.

…

The college had a cohort of students from all possible classes, castes, and religions. So it wasn’t like we were parroting elite discourse rooted in privilege. Our lived experiences and the theoretical frameworks simultaneously created a framework for us to think. Looking for intersectionality, when the word was not even used so often, was what we were trained in. Gender intersects with caste, class, race, and religion. That was the thumb rule, whether you wanted to appreciate Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare-Baire, want to giggle while reading Ismat Chughtai’s Lihaaf, or be sensitive to what is being said in Goblin Market.

I thank my teachers who knew we were lying when they excused us from the class on the pretext of attending a seminar when we were really sneaking out to watch a film in the cinema hall in the vicinity of Amba, Batra, and Alpana. …

I felt truly like the queen of the world when we hung out at the back gate of Miranda House or the hostel gate. In a conventional world, men sit on the road and gawk at women, call them names, and make them feel uncomfortable. This was the place where we turned this situation around. We sat and gawked at men. Many of us sat there, gawking at them, and they couldn’t do a thing because there were so many of us, and we had a guard at the back gate to protect us. This was revenge, or, let’s say, a piece of the planet, and the only one so far for many like me, where no man could gawk at us.

The MH lawns near the canteen, where the cats loved the muffins and coffee from the newly opened Nescafé counter, were a place that shaped our worldview. What we thought the world was and what we thought it should be were decided on these lawns. They have continued to feed my journalism for the past seventeen years.

Since I passed out in 2006, I have been in touch with many of my teachers, off and on. Some of them have generously held my hand in my crisis, written long emails to comfort me, and held the phone for hours listening to my rants about the world being so mean to anyone with feminist thoughts—Kapur and Svati Joshi being two. They didn’t have to do that, but they did, because solidarity and empathy are both taught and embodied in this manner.

…

As the twenty-first year of my association with Miranda House begins, I know why my family or any other patriarchal unit is afraid of the women in this college. They don’t know how to reason, debate, or suppress these women. They are scared of the independent beings who speak their minds and don’t wait to be rescued. They are their heroes, and they enable others to become authentic heroes. I am now a bona fide ‘bad girl’ like all Mirandians. I pray that Miranda House continues to fill up the world with ’bad girls’. That way, the world will change for the better.

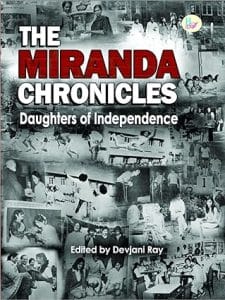

This excerpt, written by Neha Dixit in ‘The Miranda Chronicles: Daughters of Independence’, edited by Devjani Ray, has been published with permission from Har-Anand Publications Pvt Ltd.

This excerpt, written by Neha Dixit in ‘The Miranda Chronicles: Daughters of Independence’, edited by Devjani Ray, has been published with permission from Har-Anand Publications Pvt Ltd.

That women was terrorist who clamed that indian army soldier raped her .it was not true they were trying to catch her ,they fired some bullets too ,in that hustle her clothes were torn and she took that opportunity and made that look like someone raped her its not true ….posting these articles without thorough research is dissapointing .govt of that time took a selfish political decision of removing the army from that area during that time it seemed to people that this really happened but it was not true and those people still suffer the terririst took that land in their control ,it was very unfortunate ….

Plz go to retired army soldiers, chiefs and interview they ,hopefully u will get the whole story from there and then u want publish such articles which hv such bold false comments on indian army which is the most honorable system in our country

I came to Miranda House a year ago when I got admission. Being a Mirandian is my family legacy as I have 2 maternal and a paternal grandmother who also graduated from this college. When I got admission, my nani one day sat with me and told me with high praise and pride “The Miranda House girls are known for their smartness. Even in our day when we used to live near the campus area everyone used to say that don’t send your girls to Miranda as the women there are very opinionated and problematic.” And I aim to be just as such an opinionated and a problematic woman; with high opinions and raising high problems for the closed minded folks. Reading this article made me feel even prouder knowing that I get to call myself a Mirandian. No matter where I go in life I will carry this title with me. Because once a Mirandian, always a Mirandian.

This article felt like a warm hug. It echoed my thoughts.

More power to you Neha Dixit.

Thank you print for this exemplary article

Reading this just hit differently… as an English Honours grad from Miranda House (though I completed it much later, in the 2021–22 batch), I swear I still carry that same magic within me. The vibe, the grace, the raw beauty of Miranda never really leaves you… it kinda gets stitched into your being. The corridors, the adda spots, the endless chai-chatter (tho I never sipped tea lol), the literary chaos, the sudden poetry spilling in the middle of nowhere… it’s all still so alive in me. Honestly, Miranda didn’t just give me a degree,it gave me a self I still adore revisiting.

Lmao what a bunch of bullshit. So the writer got enraged by random news she saw online while ignoring her loved experience of a happy life in her home town. Classic case of being delusional on purpose.