A mythological creature with the head of a human and the body of a horse, the Buraq is closely associated with the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic mythology. While the exact details of their interactions vary over time and place, most hadiths consistently describe the Prophet as riding the Buraq during his night journey from Mecca to Jerusalem, an event known as the isra.

In some legends, the Prophet goes on to ride the Buraq through the seven heavens after the isra; in others, he ties it to the wall of a mosque before his ascension. The Buraq is also sometimes depicted as the vehicle of other Prophets in the Islamic tradition, such as Abraham.

The name “buraq” is believed to have been derived from the Arabic word bariq, meaning “shine” or “brilliance”. Some Islamic commentators have also suggested that the name is derived from the word barq (“lightning”), referring to the creature’s speed.

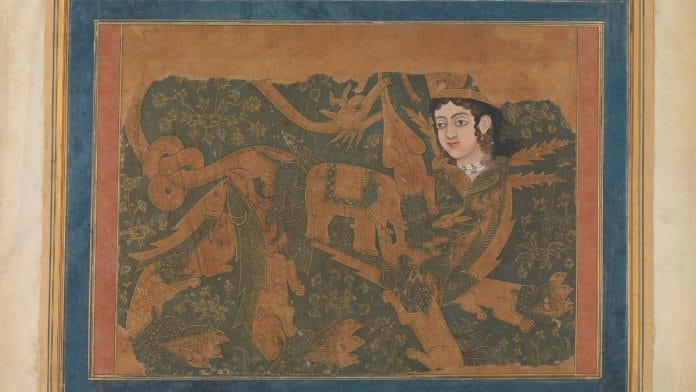

on paper; 10.2 x 17 cm | Image courtesy of Los Angeles County

Museum of Art, California

While the Buraq is not explicitly mentioned in the Quran, descriptions of the Buraq can be found in Ibn Ishaq’s eighth-century biography of the Prophet. This and other early traditions emphasise the creature’s horse-like features, including hooves, long ears, and long back. The Buraq seems to have originally been described as male, but texts from the ninth century onwards describe it as female. The first textual mentions of human facial features begin to appear from the eleventh century CE.

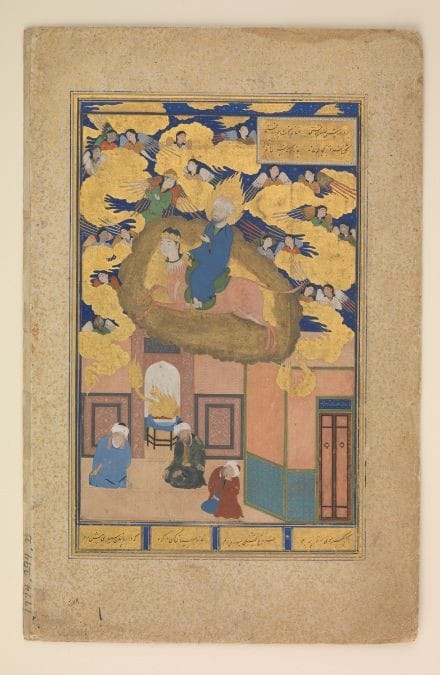

of Sa’di; Bukhara and

Herat, Present-day Uzbekistan and Afghanistan; c. 1525-35 | Ink, gold, and colours on paper;

19 cm x 12.7 cm | Image courtesy of The Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York

It is unclear when the Buraq first began to be portrayed in visual art. However, a profusion of depictions survives in Persian manuscript paintings from the late mediaeval period, suggesting the legend and iconography were firmly established around that time. Images depicting the Buraq can also be found in South Asian manuscripts depicting the isra, such as the Mi’ragnama (1436) from Herat (modern-day Afghanistan). The Buraq is the subject of manuscript paintings such as The Fabulous Creature Buraq (1660–80) from Golconda, rendered in the Bijapur style, and The Buraq Worshipped by Two Princes (nineteenth century) from Kashmir.

Images of the Buraq depict the creature with wings, the tail of a peacock, and the bust or head of a woman, often decorated with jewellery and a headdress. The creature is also sometimes depicted with a leopard hide draped over its body. In popular Islamic posters from the twentieth century, the Buraq was often presented alongside Duldul, the Prophet’s steed, as a pair. It continues to be represented in tazias (mobile shrines used in South Asian Shi’ism, specifically during Muharram) and on trucks in India and Pakistan as a talismanic motif.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission. The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.

I happen to know this one from my traditional deeni education (a choice made for me when I didn’t understand its import) but why are Bharatiya publications propagating these superstitious cock and bull stories?