The Bank of Bengal, India’s first large bank and the earliest predecessor of the present-day SBI, was the brainchild of Henry St. George Tucker, the Attorney General of the government of Bengal who eventually became chairman of the East India Company.

For the curious reader, as a matter of comparison, the gross revenue of the Presidency of Bengal in 1809–10 was approximately 9 million pounds sterling, while the total resources of the Bank of Bengal, including cash, government securities, private bills discounted and others were 8 lakh pounds, less than one-tenth of the revenues of the government.

A magnificent statue of Prince Dwarkanath Tagore greets us as we enter the present-day SBI Museum at its Strand Road premises at Kolkata. Tagore was one of the famous borrowers of the bank and had borrowed `60,000 on 21 July 1816 on deposit of Company’s paper at a rate of interest of 9 per cent per annum. The loan, as usual, was for three months or less. His name appears frequently as a borrower from 1824 in the record books.

The purpose for which the customers borrowed money from the bank on deposit of Company’s paper is not recorded in the minute books of the bank. But the Company actively promoted the entry of private European business, especially in indigo and opium. Opium was contraband in China and the Company could not directly land the drug there but it did everything short of that to facilitate the export. Another commodity which was in great demand was indigo. One of the first persons to start indigo manufacture was John Prinsep, father of James Prinsep, the great Orientalist. Dwarkanath Tagore too borrowed presumably to start his own indigo factory at Silaidah in 1821.

Also read: The banking jobs algos can’t destroy

The Bank of Bengal, supported by high government officials, many of whom had served as secretaries or directors of the bank, helped to sustain the indigo boom of the 1820s. Another item for which people borrowed money was the trading of salt. Salt was produced under a government monopoly system and then sold at certain selling outlets called salt ‘golas’ or ‘gollahs’. Since it was a seasonal business, loans for this purpose were taken during specific times of the year. More than a century later, Mahatma Gandhi’s march to Dandi for his famous Salt Satyagraha would result in questions being asked about the monopoly system.

The bank treated large borrowers like Tagore quite deferentially as they were adding to the bottom line. But that was not the case for the ordinary customers, whose treatment was similar to the callous attitude shown towards the ‘natives’ in general by the British.

The bank dealt with speed and harshness when it came to Indian debtors but showed a great deal of consideration to the European principals. The latter were granted almost complete immunity from the cruel provisions of the usual British laws related to bankruptcy by the Relief of Insolvent Debtors in the East Indies Act passed by the British Parliament on 19 July 1828. The Act seems to have been passed in anticipation of many European businessmen going bankrupt in the near future. Some debtors evaded their creditors by going away to Britain or China. Only lucky ones were spared, like Raggooraam Gossain Banian of Palmer and Co. Banian who owed the bank `1.65 lac, but he could not be arrested as he resided in Serampore (Srirampur), which was under Danish rule. Defaults had their own victims and one such high profile victim was Lord Combermere, the commander-in- chief of the British Indian Army. He lost £ 60,000, which he had deposited with Alexander and Co. and had failed to withdraw in time.

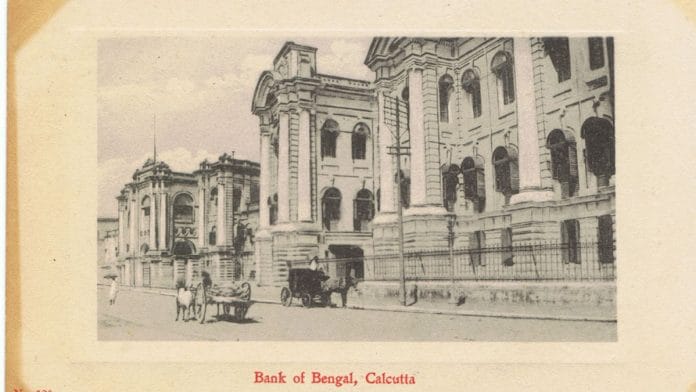

The organisational set-up of the Bank of Bengal too favoured the white man. Here too the common Indian employee suffered. The common employee’s views were either disregarded or taken very lightly. Standing on the banks of the Hooghly at 1, Strand Road, Kolkata, the zonal headquarters of the SBI, where the Bank of Bengal building once stood and which was razed a few years ago for reasons not clearly known, one can imagine the scene two centuries back.

It was not as glorious as one may want to envisage. One of the khazanchees had raised the issue of the safety of the treasury in the bank. He wrote that ‘… the Bank is on the border of the river and the only thing which divides it from public road is a low iron fence like a park railing. A small party of desperate robbers or sailors may scale it and take away the iron treasure chest which is just fifteen yards off the premises. There are only 10 sepoys to guard.’

Also read: Indian history without the Deccan is like European history minus France

The bank treated the Indian ordinary customer as it treated the small debtors—in a rude manner. This was unlike how it treated the wealthy elite of Calcutta. Quite clearly, the bank was not meant for ordinary people.

True to British tradition, the bank has maintained its records meticulously. An excerpt from the Complaints Register reveals an incident that occurred in 1889 when a customer, Potit Pabun Mitra, complained of a junior British officer, T.W.L. Bruce’s rude behaviour. The complainant said, ‘I am desirous of an apology from the assistant in the Govt. Account Dept. for alleged rudeness and that an enquiry should be conducted into the matter.’

The officer gave his explanation, ‘I have no recollection, whatever, of the occurrence, and most emphatically decline to apologise in any way to this exceedingly “under-bred” person. His letter is composed of insulting sentences, and my only regret in the matters is that his age alone prevents my taking further notice of the occurrence.’

The matter was discussed and the noting said, ‘The above is no explanation. Superintendent Govt. Acc. Dept. will please report on the matter for the Secretary’s information.’

After what may be considered an ‘enquiry’ was conducted, the following was noted in the register: ‘After enquiring into this matter, it would appear the cheque was presented just at the time the Passing Officer was commencing to enter his clearing, the Baboo however seemed to think his cheque should take precedence, and finding Mr. Bruce still continued entering his clearing cheques in preference to his, took umbrage and reported the matter. Mr. Bruce says he has no recollection of having used any such language, as imputed to him by the Baboo.’

The matter stood closed with the comment, ‘As the Baboo’s feelings have been hurt, doubtless unwittingly, Mr. Bruce having no recollection of the matter, I am sure Mr. Bruce will say the injury was unintentional and express his regret for it.’

An important banking practice was introduced by the Bank of Bengal in 1833—that of cash credit. The system was evolved in Scotland nearly a century earlier (in 1728) by the Royal Bank of Scotland. A cash credit was a credit given to an individual by a banking company for a limited sum, upon his own security and that of two or three individuals approved by the bank who became sureties for its payment.

But as was the case with many existing banking practices, the cash credit was hardly a system for the common man. The rules of business of the Bank of Bengal published in 1841 specified a minimum limit of `500 for cash credit, a significant amount in those days. By 1845, the minimum limit for opening a cash credit account at the bank had been raised to `10,000, which was beyond the common businessman’s capabilities.

This excerpt from Vikrant Pande’s ‘The SBI Story: Two Centuries of Banking’ has been published with permission from Westland Business (an imprint of Westland Publications).

This excerpt from Vikrant Pande’s ‘The SBI Story: Two Centuries of Banking’ has been published with permission from Westland Business (an imprint of Westland Publications).