Twenty years is a long time. Long enough for a memory to fade, long enough for marking a closure. But even 20 years later, Jodhpur is a town still deeply conflicted over the onscreen Bhai and the off-screen Salman Khan, with a long list of transgressions pinned to his name.

On one side are his fanatic fans; on the other, the steadfast, dedicated Bishnois. The Bishnois revere animal and plant life; in their world view, killing an animal or felling a tree is a sacrilege, punishable only by death. You can encounter their peaceful and unhurried world on the Jaipur highway, 20 km from Jodhpur. The ashram and temple of Jambeshwarji, the 15th-century patron saint of the Bishnoi community, are situated in Jajiwal Bishnoiyan in the Banad area.

Jambeshwarji espoused 29 principles from which his disciples are believed to have derived their name: Bishnois, or the ‘twenty-niners’. The drive through long stretches of bajra (pearl millet) fields feels more like a wildlife safari. The only sound one hears is the plaintive call of the peacock. Here, deer, blackbuck and chinkara, along with jackal, rabbits and nilgai, roam as freely and fearlessly as grazing cattle, even ambling into the ashram during the evening arti, looking for food.

Also read: Sultan to Bharat: Salman Khan’s mega success features a Delhi University biochemistry grad

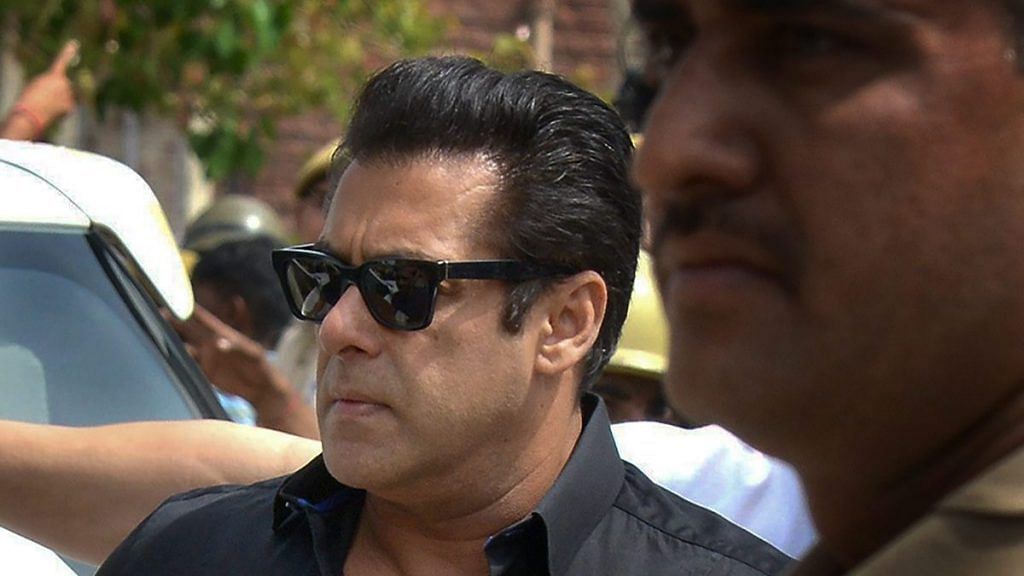

It’s these protected deer that Salman Khan is alleged to have hunted, incurring the wrath of the Bishnoi community and leading to his initial arrest on their insistence. As soon as the first shot was fired, Salman was in trouble. Bishnois living close by rushed out of their houses and chased the actor’s vehicle, a Gypsy, with seven of them astride three motorcycles. They noted down the Gypsy’s number and have been relentlessly following the case ever since.

In the absence of a definitive verdict, however, their frustration is mounting and they are, understandably, a trifle despondent. ‘The court just keeps offering one date after and another and justice keeps getting delayed, but we are sure he will eventually be punished,’ says Ram Nivas, alluding to Salman and the cases against him. ‘It’s a long struggle, but there is light at the end of the tunnel.’ Although five years have passed since I met him in 2014, I have kept in touch with him, following every new turn and development in the cases. Four separate cases related to blackbuck and chinkara poaching had been filed against the actor. In the Arms Act case, he was accused of using two firearms with allegedly expired licences, but was acquitted. The appeal subsequently filed in the High Court by the Rajasthan government is pending at the time of this book going to press.

In the two cases in which Salman Khan was accused of killing a pair of chinkaras in Bhavad on 27 September 1998 and a third one in Ghoda Farm House in Mathania on 29 September, he was acquitted by the High Court. The state government subsequently filed a special writ petition in the Supreme Court. The judgement on the fourth case, in which he was charged with hunting two blackbucks on 1 October 1998 at Kankani, was delivered on 5 April 2018, with a local court sentencing Salman Khan to five years’ imprisonment. The court acquitted the co-accused, four other Hindi film actors – Saif Ali Khan, Tabu, Neelam and Sonali Bendre – and a local travel agent Dushyant Singh for lack of sufficient evidence.

A large number of Bishnois reportedly gathered outside the District Court in Jodhpur and raised slogans against the Bollywood actor when the judgement was announced. Some of them burst crackers, shouting that justice had been delivered, never imagining that they were, perhaps, celebrating their victory too soon.

Also read: Salman Khan: ‘Main Google search mein aata hoon, samajh mein nahi’

The sentence has since been suspended, pending appeal in the High Court. At the time of my interaction with him in 2014, however, Ram Niwas has no way of foretelling these developments. He sounds hopeful as he says, ‘Hum nigraani kar rahe hain. We are keeping a watchful eye. We are working with the state government and Forest Department [on the pending appeals and the writ petitions] so that no effort is spared. We won’t let go of Salman till the very end. We will fight till the end. We are not disillusioned.’ There is pride in his voice as he speaks of the Bishnois’ passionate involvement with environmental issues and the effective information system they have in place to track down offenders who flout wildlife protection laws. Almost every Bishnoi has a mobile phone handy and every family owns a motorbike. A couple of hundred members of their group can congregate in a jiffy on hearing of any hunting or poaching incident in their territory. Lawyers from the Bishnoi community come forward to help fight cases involving such incidents, free of charge. Politically, they dominate three of the eight Assembly constituencies in Jodhpur: Phalodi, Lohawat and Luni. Hence, their word can’t be taken lightly.

Interestingly, the Bishnoi stronghold Luni, where Salman Khan was staying when the incident took place in 1998, had appealed to the actor so much that he wanted to build a house there. The case filed against him seems to have changed his perspective, however. He has come back to Jodhpur only for the hearings. Of course, the unforgiving Bishnois wouldn’t have allowed him in otherwise. They had, in fact, protested, when he was invited as the state guest in Jaipur for a marathon in 2011. ‘He has been an offender of the state and its people. So we protested against the move,’ Ram Nivas tells me three years after that incident.

‘If somebody destroys your house, you can’t invite him over as a guest and be hospitable.’ Eventually, the star did arrive to flag off the marathon, but left almost immediately afterwards, without participating in the run. The Bishnois insist, though, that there is nothing personal in their feud with Salman. Despite their anger over his poaching, no attempt has ever been made by the community to stall the release of his films in Jodhpur. Their only contention, it seems, is that he has flouted an environmental law and must be punished for it. ‘He has been a repeat offender,’ Ram Nivas firmly declares. ‘There was direct evidence of his violation of the law. What Salman did was premeditated and planned, for thrills and fun.’ He makes no effort to hide his intense dislike of the star. He can’t accept Bhai and the goodness he projects on screen. Forget watching his films in theatres, Ram Nivas switches channels if he sees Salman on television, even if it is in some obscure advertisement.

Also read: A guide to Indian prisons for Salman Khan — from Sanjay Dutt

‘I can’t accept him as a good human being on screen when he has committed such crimes. I can’t accept the show of artificiality he puts up on the screen,’ he says, grim-faced and dour. Puneet Jangu still regrets having watched the 1998 SRK–Kajol–Rani Mukerji–blockbuster Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, because he didn’t know Salman would make a special appearance in the second half. There is an unmistakable note of glee in his voice as he shares the general perception in his circle that Nawazuddin Siddiqui, a consummate actor, had stolen Bhai’s thunder in Kick. Both the Bishnois are concerned about the message Salman sends out to his admirers. ‘He is a public figure. His fans worship him. When they see him hunt, they get inspired to do the same,’ Puneet observes.

Puneet may not be too wide of the mark. Mohammad Afzal, the head operator at the New Kohinoor, claims that the hunting cases have, ironically, made the star more popular in Jodhpur and helped him widen his fan base. ‘The fact that he has been coming here occasionally for the hearings keeps him in the news and makes us connect more strongly with him,’ he acknowledges. The fandom surrounding Salman Khan was at its peak back in 2007, when the courtroom drama involving these cases was going through its most gripping phase. Every detail of the unfolding show was being discussed on Jodhpur’s streets – from the colour of the chikan kurta Salman’s then girlfriend Katrina Kaif had worn to the stubble on his brother Arbaaz Khan’s face.

Speculation was rife on how the actor would bear the oppressive heat in his cramped prison cell or whether he had struck up a rapport with his lifer cellmate Kishore Parekh. There was much concern over how he was managing to get by on basic meals of dal–roti and chana–gur in jail, how he would have to sleep on the floor and swat away mosquitoes under a single fan on a hot summer night. His bodyguard, Shera, had become the sleepy town’s new superstar by association, so much so that he himself had to be provided with security personnel. And just about every Jodhpuri could identify the Khan family’s official vehicle – the black Hyundai Terracan.

The Bishnoi’s loathing of the superstar may seem as irrational as the unquestioning love his fans reserve for him, but Salman Khan is just the kind of star who evokes such extreme responses.