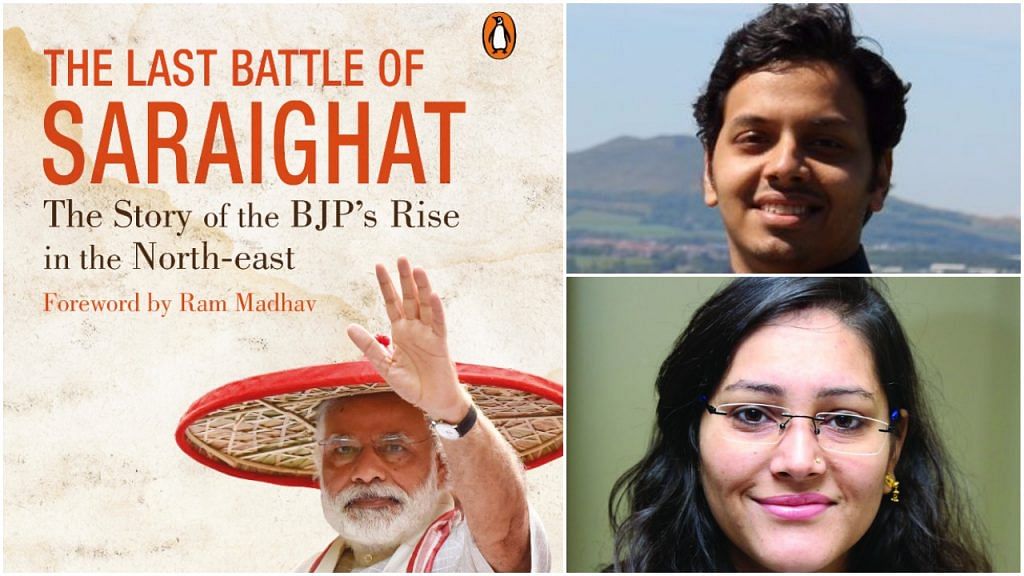

Rajat Sethi & Shubhrastha’s book eulogises the BJP’s victory in Assam, but fails to capture the true picture of the Northeast and its complex issues.

‘The Last Battle of Saraighat’ is an insider account of the BJP’s rise in the Northeast. The title alludes to the famous Battle of Saraighat that the Assamese soldiers, led by legendary general Lachit Borphukan, fought against the mighty Mughals.The Ahom army routed them in such a manner that they never considered invading the region again. In the book, the author duo tries to draw a parallel between the BJP’s landslide victory in 2016 Assam assembly election and the decisive victory of the Ahoms in 1671.

Furthermore, the authors have overemphasised the fact that the BJP’s win is nothing short of the grand victory pulled off by Ahom king Chakradhwaj Singha over Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who was represented by Rajput king Ramsingh in the Battle of Saraighat.

There is no denying the fact that the 2016 Assam assembly polls were a watershed in Assam’s political history. For this election marked the end of 15 years of the Congress regime that became synonymous with corruption and misgovernance. The last few years of the Tarun Gogoi-led cabinet saw a vertical split in the power structure with one faction commanded by the CM himself and the other, especially the young brigade, by the influential leader Himanta Biswa Sarma. Needless to say, the internal tussle in the cabinet had affected the functioning of the government—adding fuel to the mass outrage against the Congress that was gradually building up in Assam’s polity.

Until this point, the BJP did not emerge as a force to reckon with in Assam’s complex, yet dynamic socio-political milieu. There were debates and discussions onthe need for a ‘change’, but nobody talked about the BJP’s prospects since Assam is not known for leaning towards extreme Right-wing parties.

Until 2016, the voters in Assam, by and large, remained sympathetic to ‘secular’ parties – be it Congress, Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) in its previous avatars, CPI and CPI-M, CPI-ML or other regional outfits for many decades. Not long ago, Assam saw a rainbow coalition of regional and Left parties form government. Interestingly, all these episodes do not find a mention in The Last Battle for reasons best known to the authors.

A year and a half before the election, there were talks about an alternative political force or an alliance doing the rounds— but there was no clarity as to who all would be part a of it. Things changed dramatically in the months prior to the assembly elections when Himanta Biswa Sarma, who was instrumental in Congress’ 2011 election victory, quit the Congress party and knocked on the BJP’s doors.

A master strategist, Sarma enjoyed the support of many Congress MLAs who were ready to abide by his diktat although they stared at an uncertain future. However, the suspense broke as the BJP decided to welcome Sarma into its fold. And, what followed next was a new version of the BJP that shunned, albeit temporarily, its hardcore ideology of Hindutva to project itself as a ‘secular’ political force. This included key issues such as cow protection and Ram Mandir.

The swift decline in Congress workers’ morale, erosion of people’s faith in the party and the absence of a formidable regional alliance were three key factors that made the BJP suddenly relevant in Assam. This is something the authors of The Last Battle seem to have glossed over. Instead, they have constructed a narrative that the BJP’s ‘historic win’ was made possible by the RSS’s years of groundwork in the region.

While it is true that RSS has had presence in Assam for many years, it functioned as a voluntary organisation engaged in some or other form of social service. Until 2016, RSS was hardly covered by the local media in Assam. It was a non-entity till Sangh-BJP leaders from mainland India started campaigning in Assam ahead of the 2016 election, singing praises of the RSS’s take on ‘Akhand Bharat’

In fact, the authors themselves explain that Nagpur has been exporting leaders from other states to serve the people of Assam for the past five decades. “Eventually, in 2014, RSS appointed a local Assamese, Basistha Bujarbaruah, as the prant pracharak of Assam.” (P 66, The Last Battle)

So, this explains why the Sangh has failed to strike a chord with the local people all these years. Another factor that led to a disconnect between the RSS and the Northeast —known for its sub-national movements such as Assam Agitation —is its nationalist narrative. This is not to say people from this region hesitate to identify themselves as Indians or they are less patriotic than the rest of Indians. What they detest most is the imposition of certain beliefs and practices that tend to undermine their idea of India, which is diverse yet harmonious.

The authors, Rajat Sethi and Shubhrastha, worked closely with the BJP and the RSS in the run-up to the Assam election. They claim to have done thorough research on the culture and history of the Northeast before taking up this writing project. However, it would be a fallacy to treat The Last Battle as an authoritative work on the Northeast.It is a herculean task to capture a region such as the Northeast within 150-odd pages, whose issues are far more complex than the rest of India’s put together.

Jayanta Kalita is Associate Editor, ThePrint