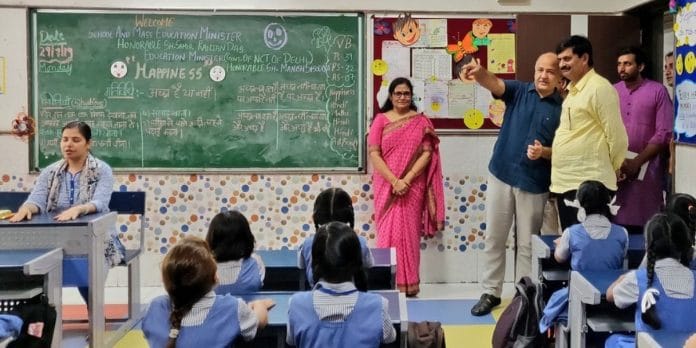

The AAP government first decided to take up the task of turning the fifty-four schools into model schools. It was an important first step to signal change to a moribund system. Some of the best engineers from the Public Works Department (PWD) were selected and tasked with turning the proposals of the principals to reality. Many governments routinely build new school buildings, but the AAP government took care to infuse these buildings with soul—each of them sporting unique aesthetics, murals and architectural designs.

The project teams were constantly pushed to deliver on the vision of building world-class infrastructure that was better than Delhi’s private schools. The classroom furniture, water coolers, toilet accessories, electrical fittings, tiling everything had to be of the best quality. Plans for each new school building and the designs of rooms, labs, libraries etc., were personally overseen and approved by Mr Sisodia and Delhi’s then PWD Minister, Satyendar Jain, a professional architect turned politician.

‘It felt like we were getting our own houses built, which was the sentiment behind this initiative,’ recalled Sisodia. The visible progress in these model schools within a year injected a shot of enthusiasm in the entire system.

Soon after the fifty-four model schools were renovated, the AAP government initiated a complete makeover of all remaining schools. In the past decade, as record capital budgets were allocated to the education department, every single Delhi government school has seen a radical physical transformation.

The revamped school buildings bore an altogether different look with mosaic flooring, clean and functional toilets, modern libraries, science laboratories, air-conditioned auditoriums, well-lit classrooms with smart boards and colourful, designer desks that were an instant hit with the children. Once constructed, systems were created to maintain this infrastructure and carry out annual whitewashing of all schools during the summer holidays.

None of this came easy. Former advisor to the education minister, Ms Atishi, recalls working for nearly nine months to fix the issue of toilets alone. The first thing she would notice entering any school building was the smell from the toilets. She figured the issue was poorly drafted government tenders. Sanitation services were outsourced on lowest rate (L1) basis without specifying the minimum quantity of cleaning supplies to be procured for each school or penalties to be applied in case of failure in performance.

After several months of back and forth with the department, a new tender was drafted to fix these gaps. This is just one example. For any new infrastructure procurement that was a departure from the past, Mr Sisodia had to spend endless hours convincing the bureaucracy why it was needed. For instance, the file for approving designer desks that cost more than twice the older desks took about two years to pass.

Also read: Does the old international order get the brave new India? What Dhruva Jaishankar says

The most immediate impact of these efforts was the increase in the number of classrooms. In nearly seven decades since Independence, Delhi’s previous governments had managed to build around 24,100 classrooms in government schools till 2015. With over 15 lakh students to accommodate, many schools had eighty to 100 students per classroom with the highest at 174 students in a classroom.

From 2015 to mid-2024, the AAP government added over 22,700 new classrooms—almost doubling the stock of classrooms in just nine years. Achieving this was no easy task since the Central government agency—the Delhi Development Authority (DDA)—that controls all land allotments in the national capital, refused to give necessary land for the construction of new schools. In the first four years, the DDA allotted only one new plot to construct government schools.

The AAP government worked around this challenge by going vertical, adding new floors and additional buildings within existing schools to optimally utilize the available space. This was equivalent to adding 613 new schools apart from the construction of sixty completely new schools bringing the total to 1,067 schools by mid-2024.

The government took special care to renovate staffrooms, turning shabby storeroom-like spaces to clean, comfortable rooms with coffee machines and a fridge. This small intervention went a long way in restoring the trust and the dignity of teachers and telling them that this new government cared.

Like every single small change that was initiated, the bureaucracy resisted even the decision to install coffee machines and fridges in staffrooms, deeming it as an unnecessary expense. An officer commented that the coffee machines can be installed but the teachers should bring their own coffee powder—an idea Mr Sisodia shot down immediately. After two years of files moving back and forth, this proposal too saw the light of day—another instance that shows how political will and persistent effort were critical in bringing about the smallest changes in the government school system.

Apart from building the academic infrastructure of classrooms, labs and libraries, the AAP government also laid emphasis on building world-class sports facilities in Delhi government schools that had the necessary space. For the first time in Delhi or perhaps any government school system in India, modern Olympic-sized swimming pools, turf hockey grounds, football grounds and basketball courts were built—that was straight out of a dream for the students. The government opened these sports facilities to any school student studying in Delhi, in any government or private school, providing free coaching too.

By March 2024, twenty six government schools in Delhi had swimming pools, seven had football grounds and three had hockey turfs that were used for training and competitions by all school students in Delhi.

An important aspect of the physical transformation was that it wasn’t limited to a few pilots or model schools, but touched each and every Delhi government school within five years. An independent assessment by the BCG in 2020 on Delhi’s education reforms brought out the deep impact of this structural overhaul with 87 per cent parents and 76 per cent teachers attesting to significant infrastructure upgrades.

Principals, teachers, parents and students reiterated that the fact that they now have access to a school that feels like a private school; that they are in an environment which is comfortable and appealing; and that small amenities, such as cushioned chairs, coffee machines in staffrooms and high quality lighting and ventilation in classrooms has been made available, has been a big driver in generating commitment and momentum.

This excerpt from ‘The Delhi Model: A Bold New Road Map to Building a Developed India’ by Jasmine Shah has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘The Delhi Model: A Bold New Road Map to Building a Developed India’ by Jasmine Shah has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This is a planted AAP propoganda article !

This is paid article favouring AAP. However all claims made are wrongfully and misleading.