The election of Zohran Mamdani as Mayor of New York last week has struck a surprising chord in the world’s media — especially considering he is technically the head of just one American city’s administration. But the buzz around this young Indian-origin Muslim, an avowed democratic socialist, is a ripple in a much older ocean.

Having delivered speeches in Gujarati, Bengali, Arabic, Hindi, Luganda, and Spanish, Mamdani is a reflection of a long-forgotten Indian Muslim cosmopolitanism. The Gujarati Muslim communities he descends from once challenged the Dutch for hegemony in Indonesia; poured money into schools, hospitals, and printing presses from Japan to Arabia; and helped the British Empire consolidate its grip over Africa. To this day, that Indian Muslim history still echoes — in high-end London auction houses as much as in the working-class boroughs of New York.

Gujaratis in the Indian Ocean

This column began with a rather innocuous tweet pointing out that Mamdani’s multilingualism would have made him a fortune in the early modern Southeast Asian spice trade. As of writing, it has racked up over one million views and 54,000 likes — and it’s a pretty accurate reflection of what propelled Gujarati Muslims to international trade superstardom in the first place.

In her paper ‘Gujarat’s Trade with South East Asia (16th and 17th centuries)’, historian Ruby Maloni describes the great port of Khambhat in Gujarat as having “stretched out two arms — one towards Aden, the other towards Malacca.” While Banias were especially prominent in East Africa and the Persian Gulf at the time, Gujarati Muslim merchants dominated the Malacca trade, conveying relatively cheap block-print textiles from manufactories in Ahmedabad deep into Southeast Asia to trade for spices.

The most prominent among these merchants effectively formed ‘dynasties’ closely linked to the Mughal court, among others. But there was also a strong aspect of caste-based collective organisation, paralleling that of Hindu and Jain Gujaratis.

Nowhere was this more evident than in Surat, perhaps the most impressive port on India’s west coast. Its multilingual babble included Gujarati, Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Dutch, English, and Portuguese. Certainly, there were clear distinctions between caste and religious groups, and within their communities Gujarati merchants — Hindu and Muslim alike — could be quite rigid. At the same time, in interpersonal and business relationships, their shared Gujarati heritage encouraged cosmopolitan attitudes.

Historian Jawaid Akhtar offers several examples in his paper ‘The Culture of Mercantile Communities in Mughal Times.’ In Surat, Armenian merchants were in business with Parsis and Muslims; Vaishnavite Bhatias, despite a taboo against crossing the ocean, jointly owned cargo and ships with Muslims. Akhtar cites documentary evidence of Bania men adopting Muslim practices such as offering dowers to their wives. Muslim and Hindu merchants also collectively represented their grievances to Mughal authorities.

On one occasion in 1669, when the Qazi of Surat compelled a Vaishnavite Bania to convert to Islam, nearly 8,000 merchants — apparently of all religions — emigrated to Bharuch in protest against this infringement of their privileges.

Gujarati Muslims quickly identified Europeans as a threat to their trade dominance in Southeast Asia. Maloni notes that Dutch East India Company records mention their difficulties with these merchants, who took them on through price wars and by installing their own candidates as port authorities. It seemed that there was nothing the Dutch could do to prevent Gujarati Muslims from trading. The Sultanate of Johor welcomed ships belonging to the merchant Haji Zahid Beg, who bought tin in flagrant defiance of Dutch embargoes. Other merchants, Maloni writes, hired cargo space on English ships; the spectacularly wealthy merchant Abdul Ghafur of Surat even flew Dutch flags on his own ships. It was only when the Dutch forcibly colonised much of Indonesia that Gujarati Muslims finally lost their grip on Malacca. But by then, new opportunities were already emerging on the horizon.

Also read: Here’s how Khilji, Akbar, and Hindu rulers dealt with Halal

The rise of ‘Corporate Islam’

As the Mughal juggernaut began to shake and unravel in the 18th century, the old order of great merchant princes and dynasties started to fall apart. Surat, repeatedly raided by the Maratha king Shivaji, faced growing competition from the East India Company’s new port at Bombay.

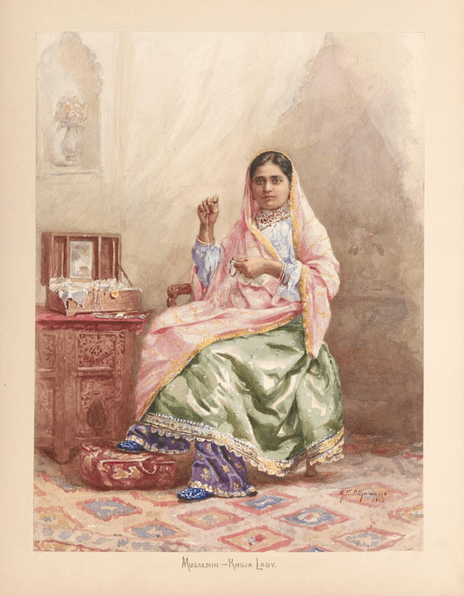

Three Gujarati Muslim communities — the Bohras, Memons, and Khojas — who had hitherto been relatively small-time traders, found themselves ideally placed to benefit from the changing political landscape. Zohran Mamdani descends from the last of these.

In his seminal book No Birds of Passage: A History of Gujarati Muslim Business Communities, 1800–1975, historian Michael O’Sullivan notes that these three groups had spread “as far east as Ujjain, as far west as Karachi, as far south as Poona, and as far north as Udaipur… They thus inhabited a territory that was, by the reckoning of an Indian lexicographer in the 1840s, larger than Great Britain and Ireland, with their shared mother tongues [Gujarati] serving as the principal language of business in Central and Western India.”

The Bohras, Memons and Khojas had all converted to Islam around the 15th century, but their social and cultural practices varied drastically. Subgroups were affiliated with various Sunni and Shia sects; some were Ismaili and revered the Aga Khans, while others traced descent by region and worshipped Sufi saints.

What these groups shared, though, was the jamaat — an institution that O’Sullivan describes as a form of “corporate Islam”. Essentially, members of each jamaat shared some resources in common — schools, hospitals, that sort of thing. Particularly wealthy members, who often held senior religious positions, also maintained private family trusts and companies.

What the jamaat ensured, O’Sullivan writes, was a mechanism for organisation, exclusivity, and interpretation, allowing these communities to adapt the changing contours of Islamic practice to an era of globalisation. Jamaats could mobilise capital, human resources, and theological flexibility at a rate few other Indian institutions could match.

Collectively, these Gujarati Muslim jamaats emerged as some of the most powerful Indian economic forces of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though now outshone in the popular imagination by Parsi and Bania entrepreneurs, Gujarati Muslims similarly negotiated with the Marathas and the British, benefited from the Opium Wars, and switched soon after to manufacturing all sorts of commercial goods, especially in Bombay.

In the 1840s, Gujarati Muslims commissioned pioneering printed texts — in Gujarati — including travelogues and cultural primers for new markets like China. Their growing wealth also funded spectacular mansions, such as those in Sidhpur, now eerily abandoned. It was Gujaratis, perhaps more than any other Indian group, who built the financial infrastructure of the British Raj in East Africa — a migration line from which Zohran Mamdani himself descends.

All of this amounted to a decisive shift in the centre of gravity of Indian Ocean Islam. It was for this reason that the Aga Khan, revered by Ismaili Khojas, moved his seat from Iran to Bombay before Partition.

Also read: Dogs were adored in medieval India. They saved cows from asuras, fought boars & tigers

A cosmopolitanism forgotten

The versions of Islam promoted by Gujarati Muslims absorbed the modernist vocabulary of capital accumulation and inheritance, frequently splintering into new jamaats as they expanded into ever-new markets and cultures.

At the same time, as researcher Danish Khan notes, Gujarati Muslims attained positions of leadership and influence in Bombay well before they had even set foot in the United States of America. “The first Muslim baronet in colonial India,” he writes, “was a Khoja and the first Muslim ICS officer was a Sulaimani Bohra. Badruddin Tyabji and Rahimtoola Sayani were the first two Muslim Presidents of Congress party. Sir Adamjee Peerbhoy presided over the first session of the Muslim League in Karachi.”

But with the rise of pan-Islamic and Hindu nationalism in the early 20th century, the scales swung once again, and mercantile, oceanic histories were overridden by grievances inspired by long-dead inland kings.

Where does the history of Gujarati Muslims fit now? Mamdani’s election is ironic on many levels. In Bombay, once the historic home of the community, a BJP politician declared, in response to Mamdani’s victory in New York, that “We won’t allow any Khan to become mayor.”

The fact is that before and since, the history of Gujarati Muslims has, for all intents and purposes, disappeared into the ever–widening gap between radical Hindutva and radical Islam. Every news cycle, it seems, tears India’s many intertwined histories further apart.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’ and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)

New york will become a slum