Karnataka, 2018, doesn’t render itself to a classical ‘Writings On The Wall’ excursion. In all my decades of watching elections, I have never seen one with so little on display: no posters, no banners, flags, hoardings or cutouts. Until, after driving through more than 2,000 km of the poll-bound state, along the highways and interiors, you approach Ballari (earlier Bellary) on its north-eastern border with Andhra Pradesh.

A narrow, but beautifully metal-topped (as most roads in Karnataka tend to be) road leads to Molakalmuru village. There is a central paramilitary forces checkpost keeping a watch at the turning. They aren’t so interested in those going in, than in the ones coming out. Why, we will find out.

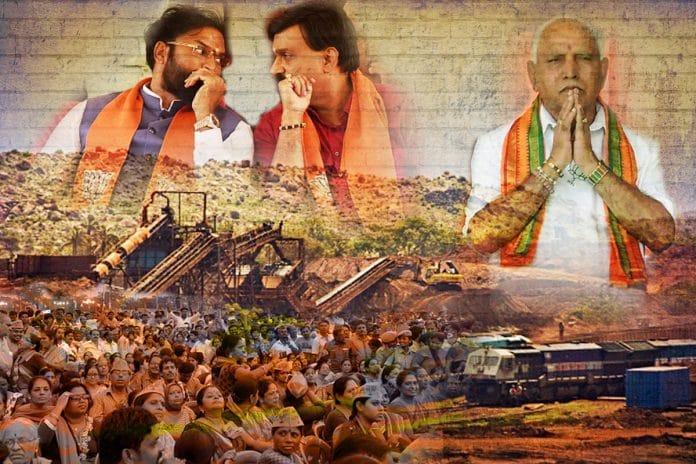

A few hundred metres in the lane, the bone-dry terrain turns to a green oasis on the right. More importantly, you find the sight you’ve been missing: hoardings and cut-outs. Staring down at you upfront are BJP’s chief ministerial candidate B.S. Yeddyurappa, and Amit Shah. Never mind that Shah has been trying to avoid any association with the resident of the “farmhouse”. Behind the two is the muscular, Telugu film star-like frame of Sriramulu, the BJP’s candidate against incumbent chief minister Siddaramaiah in Badami, about four hours away. Two brothers of the much-awed resident of the house are contesting in these polls. But his favourite, you can see, is his best friend of decades.

Gali Janardhan Reddy is the flavour of this election, the emperor of Ballari and kingmaker in Bengaluru. The BJP hopes the man facing more charges than most politicians in India will deliver most of the 23 seats in his territory, that’s 10 per cent of the assembly’s strength. The desperation to win has walked the BJP into making its most visible compromise with organised political crime and corruption yet.

Janardhan is the youngest of the Reddy trio, his older brothers being Karunakara and Somashekhara. In the last Yeddyurappa cabinet, the first two and buddy Sriramulu were full ministers with key portfolios (all important revenue and infrastructure, tourism, health and welfare, cornered between them). The three Reddy-Ballari ministers accounted for exactly 10 per cent of the cabinet positions, corresponding to the number of seats in a region aptly described as the ‘Republic of Ballari’, ruled by their dynasty. The fourth, Somashekhara, was made chairman of the Karnataka Milk Federation, which my colleague Rohini Swamy describes as a “cash-rich milch cow”.

Three of the four have had their brushes with the law. The court has granted Janardhan bail on the condition that he cannot enter Ballari district. That’s why he’s camped himself in Molakalmuru and the reason why the police are more concerned about people coming out than going in. They cannot let a vehicle with Janardhan turn right towards Ballari, his “capital”. It doesn’t particularly matter to him, though.

Also read: Me, myself and mining

Among the many immortal dialogues from the film Sholay, there’s one you recall as you walk around Ballari. It was Asrani, the jailer’s favourite boast: hamaare aadmi chaaron taraf phaile huye hain (my men are spread all over the place). Janardhan Reddy could easily borrow it today. He can’t go to Ballari, but his men, forces, brothers are all there.

We find Somashekhara on his door-to-door campaign in Ballari’s Satyanarayanapet locality. It’s a setting you can only find in a state as diverse and intriguing as Karnataka. It’s a small back-lane gathering of about 70 members of the ‘Jangama’ community, demanding Scheduled Caste status, which Reddy readily endorses. Now, who are the Jangamas? They are Lingayats. Or wait, the priests among the Lingayats and described as “gurus”. Because their caste-denominated role is to preach and teach religion to the rest. Accordingly they aren’t supposed to work but live on the devotees’ alms. They claim since their livelihood is “begging”, they should be SCs. Now, what have we got here: an even higher caste within a high caste, but demanding to be a Scheduled Caste. Then, Siddaramaiah promised all Lingayats minority status. Make sense of this. Caste politics in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar is simple arithmetic compared to Karnataka’s algebra.

We ask Somashekhara about the illegal mining cases. He claims innocence and victimisation by rivals and Congress but firmly—almost self-righteously—questions the Supreme Court order to stop all mining and auction mines afresh. “Ten lakh people are on the roads,” having lost their jobs, he says. On criminal cases, he repeats the well-rehearsed line, “Let the courts decide, justice will prevail.” But he insists all that’s been done in Ballari is “overmining, not criminal mining”.

Then I ask him about his family. Who’s the boss, who calls the shots there? “It’s Janardhan,” he says.

“But he is the youngest,” I ask with mock surprise. “No sir, he is the most intelligent of all,” the bada bhai happily endorses the chhota readily. There is no whiff of sibling rivalry. Remember, even in the earlier Yeddyurappa cabinet, Janardhan had the most key portfolios. Karunakara and his friend Sriramulu, “more than a brother”, were ministers, but Somashekhara was also entrusted with the ATM called the Karnataka Milk Federation.

To understand the mining debacle, we spend an hour with Hothur Mohammed Iqbal, the Janata Dal (Secular), or Deve Gowda’s candidate here. He heads the genteel, Urdu-speaking Muslim family that owned three large mines. There were no riches nor problems until the year 2000, he says. Then, it cost Rs 150 to dig out a tonne and it sold for 250. Rs 16.50 had to be paid to the state as royalty. So it was a marginal business. Ballari ore was also of poorer grade. Then came the Chinese boom. The price went up to 600, then 1,000 and then, bingo, 6,000. Think of the wealth it created. Mostly illegal and in black money; he obviously won’t say. But that is when excesses began, of lifestyle and mafia too. Then came the total ban and fresh auctions, both of which he describes as ‘irrational’.

Also read: Welcome to Freebiestan, also known as KCR’s Telangana

The “walls” you need to read here are the vast, dune-height ranges laden with iron ore. The darker swathes in the middle of some, a steel expert tells me, also denote manganese. All this is Ballari’s resource curse. Until the ban, it was mined on a free-for-all basis. Anybody with any permits grabbed anything around it. Everybody mined way beyond his franchise, and if you had the muscle, you merrily encroached on your neighbours’. There was no government. The only writ that ran was the Reddy brothers, especially Janardhan’s. As the Lokayukta (Justice Santosh Hegde) report pointed out in great detail, the Reddys’ own Obulapuram mine was on the Andhra side where they yielded some ore. They simply collected a share, or hafta, or protection money from everyone else. Local estimates say it would yield upwards of Rs 100 crore per day in those boom years.

Lore has it that to mine more, the Reddys shifted the state border adjoining their mines by 5 km. For the rest, please check out the 466-page Santosh Hegde report here. He estimated the total value of illegally mined and exported ore between 2006 and 2010 at Rs 1 lakh 22 thousand crores (See table).

The Lokayukta also showed that the Reddy brothers owned a mine only in Andhra, but all the ore they “exported” was of Karnataka origin, where they had no leases. These are the cases the CBI just withdrew citing lack of evidence and jurisdiction, on election eve.

I ask a senior police officer if the mining mafias here are comparable with Dhanbad. Yes, he says, but with one crucial difference. Nobody gets murdered here. Some get beaten up. But mostly, because the police and local administration were compromised, you just used them to stop the mining if somebody didn’t pay your tribute. Or, if he was persistent, get a case under a serious IPC section, including attempt to murder, registered against him. A few days in the lock-up, and not only he, but the rest were also chastened. The Lokayukta identified more than 650 officials on the take in the district. Of these, 53 key officers were ordered out. What happened subsequently is well recorded. Reddy organised a revolt against Yeddyurappa, took his loyal MLAs to a resort, recorded them on video attacking Yeddyurappa. The BJP high command wanted a truce. The price: the officers will return, albeit slowly, the Reddys will keep their portfolios and Shobha Karandlaje, considered close to the chief minister, will resign. You know why Yeddyurappa keeps saying the Reddy rehabilitation is the high command’s decision, not his. The humiliation rankles.

Excess of money led to excesses of crime and also lifestyles. Rottingly poor Ballari was suddenly awash with fancy cars, private planes and helicopters, as its new billionaires splurged. Much is gone now. Anil Lad, the Congress candidate, owned two helicopters, now sold. It wasn’t a luxury, he says, just a convenience. Because 20-ton trucks were loaded with 50 tons of ore and ripped out the highways. Now think, you overmine illegally, overload illegally, ruin the roads and then get by in personal helicopters. Most private planes are now sold. Except Janardhan still has two helicopters.

Let me try to sum up Writings on the Wall from India’s most resource-cursed zone. All three candidates here are former miners. One (JD-S), lost two of his three mines; the second, Congress, lost all his mines; and the third, the BJP’s, didn’t particularly lose many mines because he hardly owned any. Just that all who allegedly paid him a tribute from their mines lost theirs. All of them are hoping that the election result will somehow bring back the good times. Global prices are moving up again.

हिंदी में पढ़ें : विवादित बल्लारी भाइयों की वापसी से मालूम होता है कर्नाटक के लिए कितनी बेक़रार है भाजपा