India’s neighbourhood is reeling under extremely high rates of food inflation, causing massive political uncertainty. Within its domestic borders, retail food inflation is catching up too. In March 2022, India’s retail food inflation rate was 7.7 per cent, up from 5.9 per cent in February and 4.9 per cent a year ago. While inflation in vegetables, oils and fats, and livestock products was extremely high, that in cereals and products was under 5 per cent.

This is largely attributed to the Narendra Modi government’s decision to increase the supply of free foodgrains under the public distribution system (PDS) through the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY). Even though the peak of the Covid pandemic has subsided, the government has decided to extend the free distribution of 5 kg foodgrain per person per month for a period of six months from April to September 2022.

Due to the ongoing Russian war on Ukraine, the global prices of foodgrains have skyrocketed and Indian exporters are signing large contracts for the export of wheat and rice. The exporters and traders are sourcing wheat from various states, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. But do we have enough to supply the domestic markets?

We examine the implications of global food shortages on rice procurement in the remaining period of Kharif marketing season (KMS) 2021-22 (April to October) and wheat procurement in Rabi Marketing Season (RMS) 2022-23 (April to March) on central pool stocks in India in FY 2022-23. We use a balance sheet approach to assess the extent of surpluses with the Food Corporation of India (FCI).

FCI’s buffer stock situation

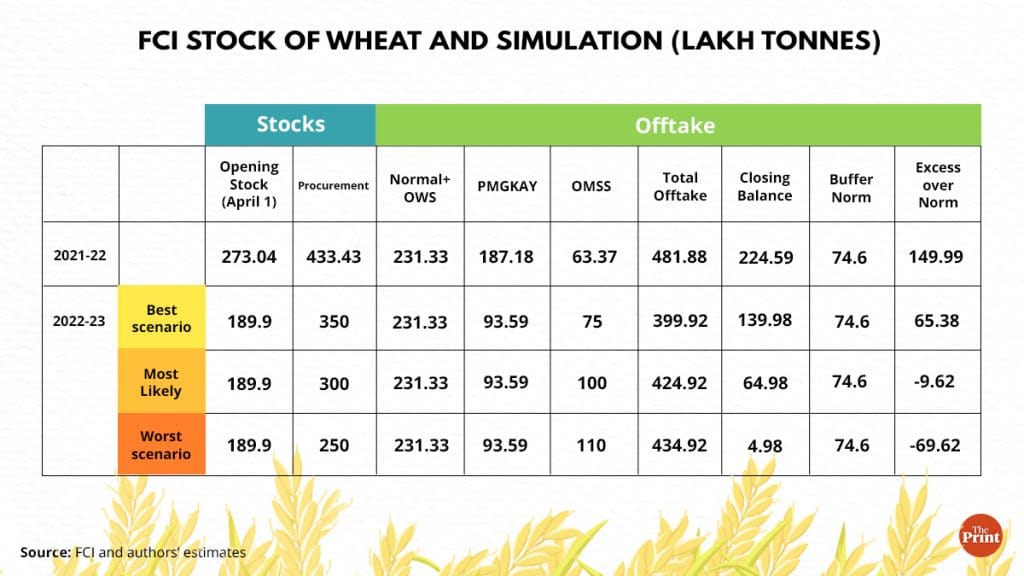

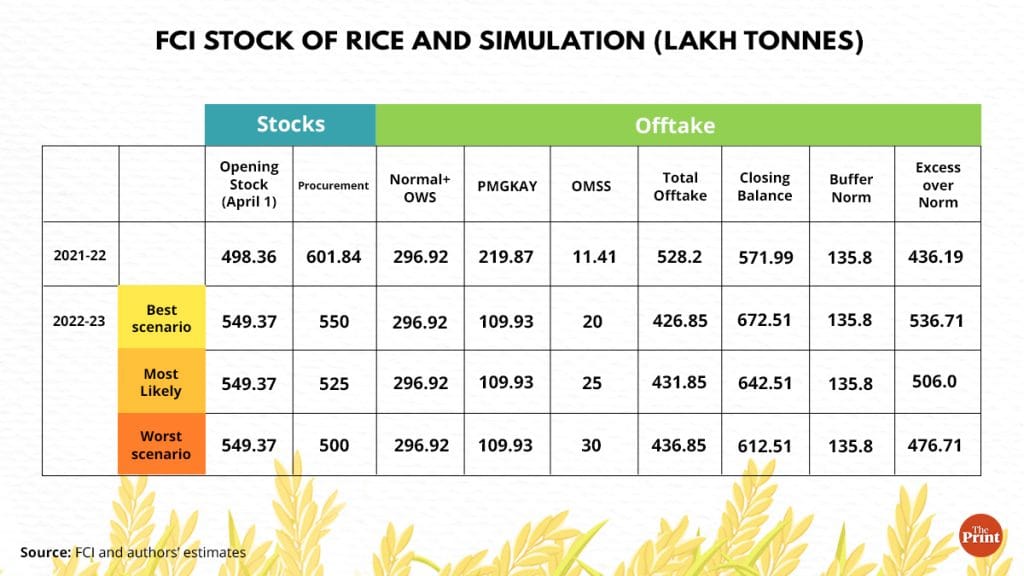

On 1 April 2022, the stock position of wheat in the central pool was 189.90 lakh tonnes. It was 2.5 times the buffer norm of 74.6 lakh tonnes. On this date, the stock of rice, including rice from un-milled paddy, was 549.37 lakh tonnes, while the buffer norm was 135.80 lakh tonnes. Thus, the rice stock was about four times the buffer norm.

Trends in production, procurement

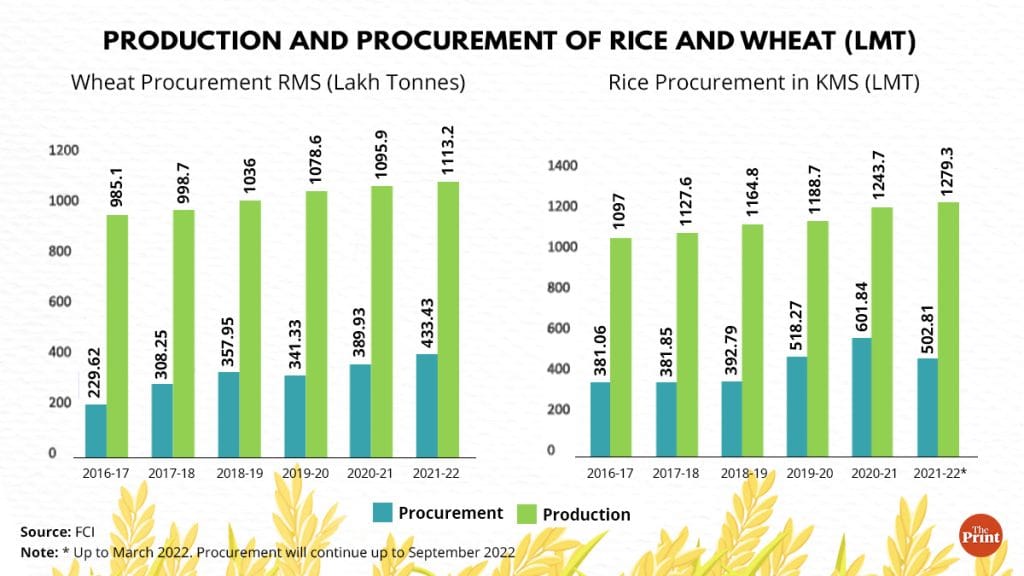

In the last five years, India has been producing and procuring more rice and wheat each successive year. The production of wheat in FY 2020-21 was 109.59 million tonnes, out of which 433.43 lakh tonnes was procured in RMS 2021-22. Wheat procurement in previous RMS 2020-21 was 390 lakh tonnes (Figure 1).

In the case of rice, the production in 2020-21 is estimated 124.4 million tonnes, out of which 60 million tonnes was procured by the government agencies. In the last five years, while wheat production grew at a growth rate of about 2.5 per cent (CAGR), its procurement grew by 14 per cent. In the case of rice, while production grew at about 3.1 per cent, its procurement grew by about 6 per cent.

Figure 1: Production and Procurement of Rice and Wheat

Wheat stocks and simulations

Despite higher procurement in RMS 2021-22, the wheat stock in the central pool on 1 April 2022 was 83 lakh tonnes less than last year. This is because the offtake of wheat under the PMGKAY was much higher at 187 lakh tonnes in FY 2021-22 against 107 lakh tonnes in FY 2020-21.

Table 1: FCI stock of wheat and simulation (Lakh Tonnes)

To assess and forecast the situation of wheat stocks in the central pool, we present some scenarios where we simulate varying levels of procurement and Open Market Sales Scheme (OMSS) releases for FY 2022-23 (Table 1). In two of the three scenarios, it appears that by April 2023, the central pool may have less stock than the buffer norm of 74.6 lakh metric tonnes (LMT).

Rice stocks and simulations

On 1 April 2022, the central pool had about 549.37 LMT of rice (including un-milled paddy). Upto March 2022, the rice procurement is 503 lakh tonnes, while in the same period in KMS 2020-21 (October to March), it was 465.5 lakh tonnes. So, rice procurement by the end of KMS 2021-22 in September may be higher than last year’s 600 lakh tonnes despite the Union government’s decision to procure a lower quantity of (boiled) rice in Telangana.

The distribution of rice under the PMGKAY in FY 2021-22 was 220 lakh tonnes, only marginally higher than the 208 lakh tonnes of the previous year. This is possibly the reason for the accumulation of much more rice than wheat in the central pool.

Table 2: FCI stock of rice and simulation (Lakh Tonnes)

Similar to wheat, we undertake a scenario building exercise for rice (Table 2). We apply different levels of procurement and OMSS sales under different scenarios. In all three of them, the central pool stock of rice is not projected to face any shortage by April 2023.

Also read: Why Indians have to resign to the fact that food prices will stay high this year

What lies on the horizon

At this point, we need to sound caution on some issues.

One, the data on wheat procurement so far does not look too good. As of 18 April 2022, UP procured only about 30,000 tonnes of wheat against 3 lakh tonnes last year. In MP, too, the procurement is only about half of last year’s. The centrality of Punjab and Haryana in providing food security to India may therefore be proven yet again.

Two, due to the higher-than-normal temperature in March, there is a possibility of yield losses in wheat, especially if sown late. Anywhere between 10 to 15 per cent of yield loss is being assessed by the trade due to high temperatures. Lower yields would affect the wheat available for procurement.

Three, the Russian war on Ukraine is already squeezing global wheat supplies. In March 2022, US hard red winter (HRW) was selling at US$486/tonne, which was about 78 per cent higher than last year’s price of about US$ 273/tonne. Higher global prices offer lucrative export opportunities to Indian exporters. Substantially higher export would further squeeze the domestic availability of wheat.

The likely shortage in fertiliser supplies is another area of serious concern. In view of the steep rise in global prices of phosphatic and potassic fertilisers due to the Russian aggression, there is an urgent need for the Modi government to clarify its policy on the Nutrient Based Subsidy (NBS) Programme. It is important to ensure that the availability of fertilisers is not adversely impacted due to the reluctance of private trade and fertiliser companies in signing contracts for import.

Lastly, the performance of the monsoon in 2022 will be a big factor in the production of kharif crops, especially rice. In case the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD)’s prediction of a ‘normal monsoon’ materialises, India may be able to have ample domestic availability despite much higher exports. However, if monsoon rains are erratic in major paddy-growing areas as hinted in the IMD’s 14 April release, there may be a reduction in paddy production.

Overall, it appears that even though India has had an excessive stock of wheat and rice in the central pool in the last few years, this situation may change this year, particularly in the case of wheat.

At this point, it is important to recall the situation of rice and wheat back in FY 2004-05. Between 2000 and 2005, India encouraged unlimited exports of wheat and rice. As a result, 213.6 lakh tonnes of wheat and 131.25 lakh tonnes of rice was issued from central pool stocks (under OMSS exports). The result was that wheat stock fell to about 20 lakh tonnes by 1 April 2006 against the then-buffer norm of 40 lakh tonnes. The result was that the government had to import 55 lakh tonnes of wheat from 2005 to 2007 to meet its own PDS requirement.

Therefore, there is a need for the Modi government to assess food inflation and the domestic requirement of wheat and rice in a war-ravaged year. The export policy of wheat and rice also needs to be fine-tuned after taking into account the emerging global food situation.

Siraj Hussain is Visiting Senior Fellow at ICRIER. Shweta Saini is an independent researcher. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)