India’s balancing act was evident at the Ukraine peace summit in Switzerland. Despite regular participation at all multilateral summits addressing broader security issues emanating from the Ukraine war, New Delhi did not sign the joint communiqué released after the Switzerland summit.

A string of sharp reactions followed New Delhi’s stand. Many in the West have criticised India for falling short of expectations as a country seeking to be a mediator. However, equally vociferous rebuttals have also justified the stand because sustainable peace in Ukraine cannot be achieved without Russia on board.

These reactions miss a set of critical elements that make the pursuit of just peace in Ukraine an evolving process.

A peace summit won’t solve problems

The Switzerland peace summit became a victim of wrong messaging. The war in Ukraine is far from over. It is unreasonable to assert that this war can be brought to an end with a peace summit organised by a specific country. The event should have been projected as a step in an evolving process that would eventually help bring Russia on board. It was, however, portrayed as one of the final visions for peace in Ukraine. That is where it went wrong.

This incorrect communication, perhaps, is the primary reason why several countries avoided signing a document that could be interpreted as taking sides in a war. These countries included BRICS members Brazil, India, and South Africa, which are just months away from attending the next BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia.

However, the joint communiqué was also a diplomatic exercise unto brevity with three main points covering specific issues. Impressive developments have already been made in these areas in previous summits, all with India’s participation.

Collaborative peace in Ukraine

At least four peace summits have been organised by different countries since the direct mediation efforts by Turkey – attempted shortly after the war started – failed. Russia has not been invited to any. China has been invited to all but has attended only one.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy came up with a 10-point peace plan in November 2022, which argued for broad securitisation of the region apart from upholding his country’s territorial integrity. It addressed issues of nuclear safety, food security for Asian and African countries, protecting Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, exchange of prisoners of war, and handling of ecological damage. All of these issues had implications for a broader security complex going much beyond the borders under war. From the get-go, Zelenskyy made this peace plan a rallying point for adding traction to his government’s diplomatic outreach to the world.

The first meeting on the Ukrainian peace plan was held in June 2023 in Copenhagen and included high-level officials from the G7 (and the European Union). It also comprised India, South Africa, Brazil and Turkey. A broad consensus was agreed upon but no joint statement was released or signed. China was invited but chose to not attend.

A few months later, a second meeting was hosted by Saudi Arabia in Jeddah in August 2023. It had representatives from over 40 countries including China as well as from several other emerging economies (including India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval). The key takeaway—Jeddah talks were instrumental in setting up working groups on the various themes of the Ukrainian 10-point peace proposal, especially those that addressed the wider security complex.

A third meeting was hosted by Malta in late October 2023 and this time, national security advisors from 65 countries in Europe, South America, the Middle East, Africa and Asia participated. China ducked the invitation this time as its own peace plan, released at the beginning of 2023, failed to coalesce international solidarity or legitimacy.

China’s peace proposal was all about a central position for Beijing as a mediator and had little room for collaborative manoeuvres at peacebuilding in Ukraine. It was also infamously ambiguous on the question of territorial integrity resorting to nothing more than mere lip service to international law and the United Nations charter.

However, all other BRICS members except China and Russia participated in the Malta talks. A joint statement, although awaited, was not released.

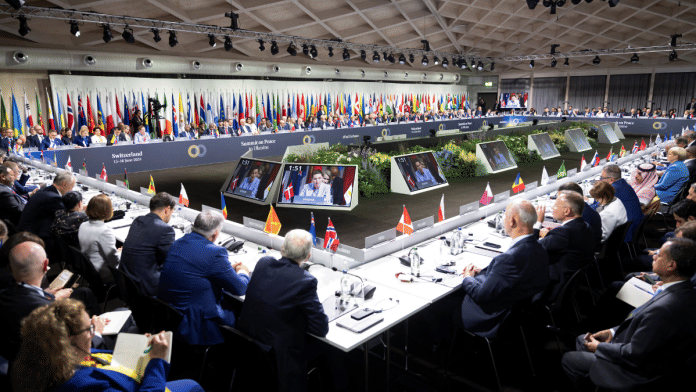

The most recent summit in Switzerland in June 2024 was the fourth leg of collaborative peace summits and, barring Russia and China, was attended by an overwhelming 92 countries and eight international organisations.

The key difference between the previous three summits and this one was the release of the joint communiqué that India and a handful of other countries like Brazil, Saudi Arabia, UAE and South Africa chose not to sign.

The success of these summits should be viewed from burgeoning international participation. A dozen countries choosing not to sign the JC is more a message for the domestic audience and a continuation of neutrality than anything else.

Going by participation metrics, the four summits held thus far have shown steadily growing solidarity for building peace in Ukraine.

Also read: Ukraine summit strives for broad consensus to lean on Russia to end war

India’s nuanced position

India has stayed committed to the UN Charter and the ideals of territorial integrity and sovereignty. When juxtaposed, this stand complements New Delhi’s abstention from recognising the annexed territories of Donbas, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson by Russia in 2022. And it should be interpreted as an endorsement of international law.

Its position on Ukraine has hinged on twin dynamics since the beginning. First, that lasting peace cannot be achieved until Russia is on board too. Second, that India would be committed to the UN charter.

Additionally, India had also abstained from the two UN General Assembly resolutions on Ukraine – A/RES/ES‑11/1 and A/RES/ES-11/6, which were quoted as a precursor to the joint communiqué. Not signing on the latter should hardly come as a surprise. However, neither UNGA resolutions nor joint communiqués have hindered India from being part of all relevant brainstorming on Ukraine in a constructive manner.

India’s refusal to sign a joint communiqué has been made to look like the only position it has held, belittling New Delhi’s long-standing commitment to building peace in Ukraine. India has sent to Ukraine more than 15 consignments of humanitarian aid, which shows that its commitment goes beyond lip service.

The strength and expanse of Russia’s clout among emerging economies should be analysed too. There has been no peace summit organised or hosted either by Moscow or by one of its closest and most prominent allies, Beijing. It is worrying that when Moscow organised the Russia-Africa Summit in 2023, the number of participants dropped from 43 in the previous year to 17. In the same year, President Vladimir Putin chose not to physically attend the BRICS Summit hosted by South Africa for fear of being arrested despite assurances from South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Putin is seen repeatedly visiting merely a handful of countries –mainly China, lately North Korea, and now Vietnam. He is doing this instead of gathering diplomatic support for his terms to end the Ukraine war, or getting more backers for China’s pro-Russia peace plan.

Ukraine, by comparison, has been more successful in aligning a tremendous amount of diplomatic presence. This has helped forge a collaborative way forward to address issues requiring broader engagement.

Despite historical and abiding ties with Russia, India’s consistent position in supporting collaborative peace-building in Ukraine has real merit, even with limitations. Not signing a JC is neither going to derail the already established working groups formed at the Jeddah summit, nor does it help Ukraine on the battlefield.

What is going to help Ukraine is the resolve and commitment shown by Europe and Europe alone. If Donald Trump’s comeback in the United States becomes imminent, the EU, United Kingdom and NATO will emerge as the key actors deciding the fate of Europe’s security. India’s approach toward a lasting solution for the Ukraine war will not be decided by its abstinence from joint communiqués; it will be decided by Europe’s actions on the ground. That’s where the buck stops.

The writer is an Associate Fellow, Europe and Eurasia Center, at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Already 28 months. How much longer should peace conferences wrestle with the idea. What can bring a very early ceasefire. With G 7 and Russia, China so far apart, difficult to be sanguine about a peaceful, prosperous future for Ukraine, likely with EU membership and security guarantees short of NATO membership. 2. Territorial integrity. That is the tough one. Starting with Crimea.