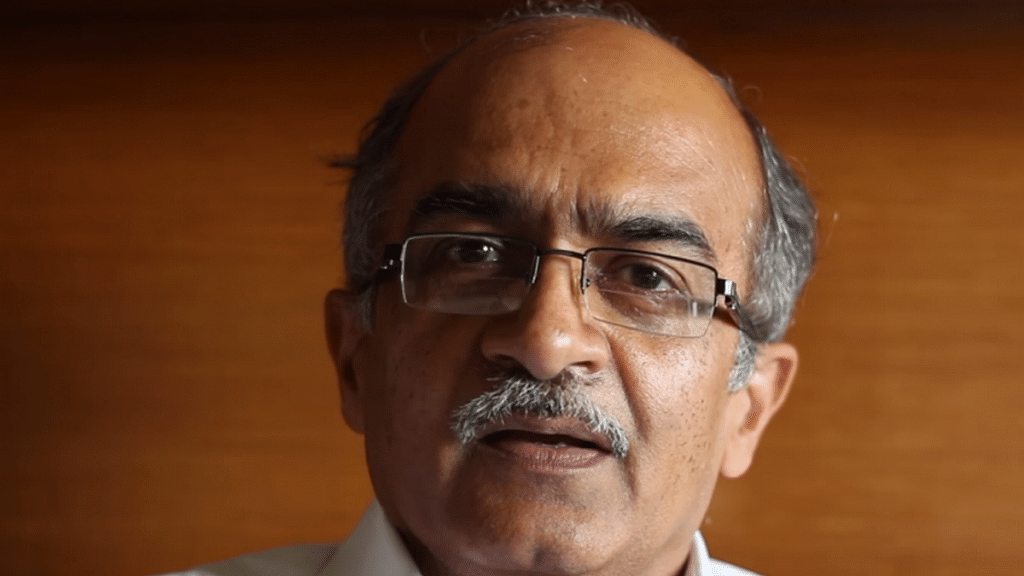

What is wrong in seeking apology?” asked Justice Arun Mishra famously to lawyer Prashant Bhushan this week. “Apology is a magical word,” he reportedly said while assuring Bhushan that he would be elevated to the level of Gandhi if he did so. When Bhushan’s lawyer seemed unwilling to take this flight to Mahatmadom, Justice B.R. Gavai helpfully reminded that Gandhiji used to fast for the sin of others as well.

We do not know how Prashant Bhushan or his counsel Rajeev Dhavan reacted to this suggestion. Dhawan was at his brilliant best that afternoon, but in his wisdom let this one go. Social media was less reverent and has since exploded with cartoons, memes, jokes, tweets and comments on this unusual request. That’s a lot of fun, but it still does not answer the question: what is wrong with an apology?

Prashant Bhushan could turn to Socrates and Gandhi for an answer. After all, the most famous account of the trial and punishment of Socrates, the dialogue written by his famous disciple, Plato, is called The Apology. Not many remember that this was Gandhi’s favourite book of Plato. So much so that he had done a Gujarati translation of this dialogue in 1908. In Greek, apologia did not mean what we mean by apology today. It meant speaking in defence or offering an explanation, just as Prashant Bhushan did in his affidavits.

Prashant Bhushan could have answered Justice Mishra thus: There is nothing wrong with seeking an apology. It is indeed a magical word, whose utterance can repair relationships, an act that can heal deep wounds, an acknowledgment that can begin to undo historical wrongs. Provided — and that’s critical — it meets some basic conditions of what counts as an apology.

Also read: ‘Insincere apology will be contempt of conscience’ — Prashant Bhushan refuses to apologise

Apology as remorse

Bhushan could remind Justice Mishra that a true apology must meet five conditions. There should be a wrongdoing in the first place. There must be a mistake, an error, something morally wrong, for an apology to be initiated. Two, there should be an acknowledgement, an honest admission, of the wrongdoing. Three, there should be a willingness to accept full responsibility for the damage or the consequences of the wrongdoing. Four, there should be genuine remorse accompanied by an expression of regret at what happened. Finally, there must be a commitment not to repeat the mistake.

So, apology is not just a word. It is not to be furnished at one’s convenience. Or worse, a legal trick to wriggle out of responsibility. A true apology must be a deep ethical act of introspection, self-reflection, atonement and self-reform. In its absence, an apology can be farce and duplicity, if not worse. Bhushan could have cited Rajeev Bhargava: “Insincere and fake apologies are morally useless and socially ineffective. Far from repairing fractured relationships, they only cause further damage.” Thus, a true apology emanates from within, in the process of a sincere dialogue, without any coercion or manipulation.

Also read: Unity is not conformity — India should know that as Prashant Bhushan is convicted for contempt

Apology as power play

This is not what was happening in the Supreme Court. Prashant Bhushan had repeatedly said that his tweets contain his bona-fide belief, that he continued to hold those beliefs, that their public expression was his highest duty as a citizen and as an officer of the court. So, the first step to demand an apology would have been to show that there was wrongdoing, that Prashant Bhushan’s tweets were untruthful. This did not seem to interest the court. While it made an attempt to show that his tweet about the court being in a “lockdown mode” was incorrect, the court’s order did not go into Prashant Bhushan’s tweet about the role of the court and the CJIs and the health of the democracy. The court seemed to be saying that whatever hurts the judges, true or false, is in itself wrong. By that logic, Prashant could ask, the hon’ble judges must offer dozens of apologies every day because they hurt all those who do not get favourable orders.

The apology Justice Mishra was demanding was not in the arena of dialogues. When a teacher pulls a student by their ears and asks them to offer an apology before the entire school or when a panchayat gathers the village and asks an ‘errant’ couple to tender an apology, be sure that neither the couple nor the student feels any inner remorse. An apology in this setting does not emanate from a self realisation; it is a demand for compliance, an acknowledgment of authority. This is not a relationship between the persons who give and receive apology; this is a public spectacle of humiliation. Saying sorry under duress is simply surrendering to external power.

Also read: Prashant Bhushan is a selective crusader for democracy, with a cussed streak of intolerance

A satyavir

Even so, what is wrong with this kind of an apology, an acknowledgment of superior power? For an answer, we must again turn to Gandhi. In his translation of Plato’s Apology, Gandhi describes Socrates as satyavir, a soldier of truth, who did not back down even when faced with death penalty. If Socrates had recanted his beliefs to please the jury or wriggle out of trouble, this wouldn’t be a magical apology. This would have betrayed shallow conviction and cowardice.

Gandhi faced this situation when the court in Ahmedabad tried Mahadev Desai and him for committing contempt of court through a publication. Gandhi tells us why he chose not to apologise:

“I wish to assure those friends who out of pure friendliness advised us to tender the required apology, that I refused to accept their advice, not out of obstinacy but because there was a great principle at stake. … I could not offer an apology if I was not prepared not to repeat the offence on a similar occasion. Because I hold that an apology tendered to a Court to be true has to be as sincere as a private apology… if I did not apologise, I did not, because an insincere apology would have been contrary to my conscience. I hold that it was about as perfect an instance of civil disobedience as it ever has been my privilege to offer. (Young India, 24-3-1920, pp. 3-4)

An apology may not make you a Gandhi, but in some situations, it is a very Gandhian thing to do. In some other context, a true Gandhian must refuse to offer an apology. That’s what Prashant Bhushan did.

The author is the national president of Swaraj India. Views are personal.